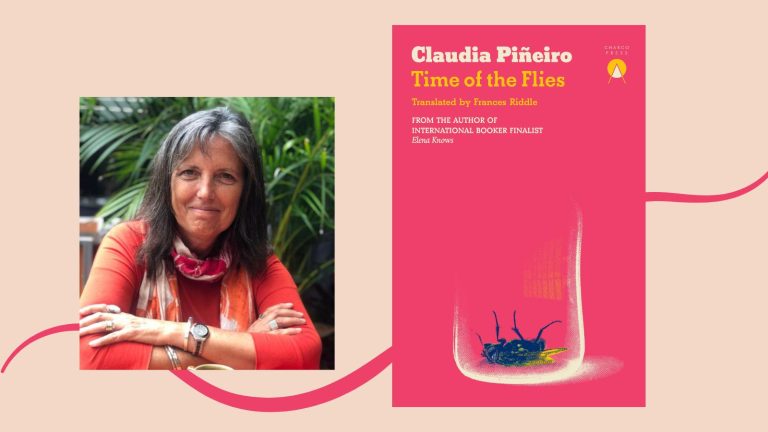

“I Like to Dive Into Those Questions That We Still Don’t Have Answers To”, Claudia Piñeiro on ‘Time of the Flies’

02 September, 2024Claudia Piñeiro has spent over two decades penning fiction about the lives of women in Buenos Aires, where dark events—affairs, accidents, suicides, and murder—turn their worlds upside down.

Piñeiro weaves in the political backdrop of Argentina with the psyche of her characters, giving her stories a rich depth that has earned her accolades as a best-selling author, and the third most translated Argentine author behind Borges and Cortázar. This year, Netflix released a film adaptation of her Booker Shortlisted novel, Elena Knows, led by a stellar performance by Argentine A-lister, Mercedes Morán.

Piñeiro’s new book Time of the Flies is a sequel to her 2005 novel, All Yours. Her protagonist, Inés, has been released from prison after killing her husband’s lover—the murder which happened in All Yours. But soon after her release, Inés is asked to be complicit in another crime. She’s unsure whether she wants to go down that path again, despite the desperately needed reward money.

During this year’s Women in Translation Month (#WITMonth), Sounds and Colours spoke to Piñeiro about her subjects, writing process and why Buenos Aires is always at the heart of her books.

S&C: You’re often described as a crime writer—which I’ve always found quite strange given how broad the topics of your books are. How do you feel about the description?

CP: I was surprised when they first called me a crime writer. I write stories—in those stories, death appears.

We could say that my stories have certain elements of the detective genre—but in a way where the genre’s rules are subverted. For example, some say Elena Knows is a detective story. I believe the reader quickly understands what happened—the one who doesn’t know what happened is Elena herself.

In a detective story, one asks questions about the past— ‘Who killed them? And why?’ In Time of the Flies, the questions are about the future. ‘What will these women do? Will they accept the request? Will they go to jail again? If they kill someone, who will they kill?’

Sometimes I get invited to crime book conventions and I don’t mind that. Every reader has their interpretation.

As you mentioned, all your books hinge on different events. A Little Luck is an accident. Elena Knows, a suicide. In Time of the Flies, it’s murder. They are very psychological—it feels narrowing to pin you down as a crime writer.

My books have layers of different elements. Some readers engage with just one layer. Others engage with several layers. Some might enter a layer that no one else does, but you can enter through different places. For some, the entry point might be the detective aspect, but not for me as a writer.

Your work engages quite a lot with South America’s feminist movements. In Time of the Flies, you explore the word “femicide”—can it be done by a woman to another woman? Or is it just at the hands of a man…? Could you explain your questioning in this book?

I try to address the discussions within the feminist movement. Maybe I don’t have the right answer.

Today, where many countries are shifting to the right, including my own, the term “feminicide” is being questioned. So I think it’s much more important to highlight what “feminicide” is. Some countries have accepted the concept of feminicide, but then a conservative party is elected and starts questioning whether feminicide exists because “men are also killed”.

“I try to address discussions within the feminist movement”

That’s an absolutely ignorant conclusion. Feminicide, or femicide, refers to the killing of a woman simply because she is a woman. So, more men are killed than women each day. Yes, but they are killed in muggings, in various situations. It’s not that they are killed because they are men. In contrast, with women, what we’re addressing is a hatred toward women. It’s a situation where a man, in general, goes and kills a woman.

What the novel tries to do is push this to the extreme. Some women hate other women simply for being that type of woman. But, it’s more of a reflection brought to an extreme level—that there are also women who are sexist, who are patriarchal. But the reality is that murder is committed 99% of the time by a man.

Ethically, it would have been more straightforward if Inés killed her husband, rather than her husband’s lover—but you decided to take a path that’s morally more blurred…

So, twenty years ago I wrote the book, All Yours, where Inés kills her husband’s lover. Inés was a completely patriarchal woman. She would have remained married to that man, even if he had been unfaithful. So, Inés from 20 years ago doesn’t kill Ernesto because, despite everything, she still wants to be Ernesto’s wife.

Now, 20 years later, Inés is in prison. With the [rise of] the feminist movement, I think we all [have changed]—including me, as a writer. I don’t know if I would write Inés now the way I did 20 years ago.

When I wrote Time of the Flies, I already knew that Inés had killed the lover because Inés was an entirely conservative woman. Inés emerges from prison as a different woman. The world has changed radically. She has to change too. She can’t become the best feminist in the world overnight, but gradually, there are things she can adjust to. Her friend Manca helps her make those changes.

A male journalist asked me why Ernesto isn’t in Time of the Flies. And it’s precisely because her evolution involves breaking away from Ernesto. Any friend would tell her, “Enough with Ernesto; don’t let him be a part of your life anymore.”

I hadn’t thought about how the rise of the feminist movement had changed the discussion so much within those twenty years that Inés was in jail…But of course that makes sense.

This novel, instead of discussing issues externally—like we have for so long, fighting for our rights and our place in the world—focuses on internal reflection. That’s why there are different voices of women who, even within the feminist movement, may have differing opinions.

In classical Argentine culture—for example, golden age tangos—many works describe the trope of a “crime of passion”. This is a controversial term as it has been historically and judicially used to justify the murder of women as acts of love. Are you exposing the hypocrisy of that term by focusing on female murderers?

As you say, I try to never use the term “crime of passion” or any similar words, not for a man or a woman. A “crime of passion” implies that it was someone’s fault because there was passion and love. But in reality, what’s happening is something else—it’s murder, it’s hate.

“This novel, instead of discussing issues externally—like we have for so long, fighting for our rights and our place in the world—focuses on internal reflection.”

Of course, tango in Argentina constantly has those kinds of absolutely sexist [elements]. I think there’s a whole education through music, poetry, TV series, and movies which is now being dismantled. But for many years, we were taught by that kind of sentimental education — it’s been a problem for generations.

People writing now have a responsibility— to be aware that we are creating a different kind of sentimental education. This doesn’t mean it’s not literary. One thinks in literary terms, telling a story from a literary perspective. But I’m also aware that someone is reading on the other side. That what we write, in a way, shapes the unconscious and collective mindset of certain generations.

It’s not just what one person writes; all the literature of an era shapes the mindset of that time. And that also comes with a certain responsibility as a writer.

We’ve spoken about the feminist movement. When I read the book I do feel compassion for Inés, that she was bullied, gaslighted and manipulated by Ernesto. Do you write your books in dialogue with social movements, and if so, how is the current right-wing Argentine government of Milei shaping your work?

It’s never that I’m writing about what will happen; I’m always writing about what is happening. As writers, we have—as Antonio Tabucchi says in Autobiografías ajenas—our antennas up, quickly detecting what’s around us. We detect things, put them into words, and invent a story. If that story isn’t real, if it doesn’t exactly match the world, it doesn’t matter because we’re not sociologists, anthropologists, or scholars of social movements.

Often, these stories we invent seem to come before the actual processes, but they were already there, right? My novels are very contemporary. I think Time of the Flies is very contemporary. What’s happening in that novel is happening in different countries.

There’s a regression now in Argentina. We now have an abortion law that was passed last year, but every so often, voices question whether it can be repealed. We had comprehensive sexual education programs in schools but this government is removing them. In the [government’s] advertisements, they show boys dressed in blue and girls dressed in pink, which is something we know, as feminists and educators, are stereotypes. We fight to break them. I don’t know how long we can resist.

The novel I wrote this year has a lot to do with this. I start writing a story, my characters go out into the world. What they encounter is what I encounter too. And it has a lot to do with questioning the things being debated within feminism. In this case, the [new] novel is more about sex work. There are many divisions within feminism on whether it should be allowed, regulated or abolished. I like to dive into those questions that we still don’t have answers to.

Can’t wait to read it! You’ve been busy with a lot of projects—a Netflix adaptation of Elena Knows recently premiered. It was interesting to visually see the city and the journeys Elena has to make to solve the mystery of her daughter’s death. What did you think of it?

It’s a very intense movie, and Buenos Aires is very much present because it’s about the journey of a person with Parkinson’s disease travelling from the outskirts of Buenos Aires into the city. So, while this trip might take 40 minutes for someone else, for her, it’s almost like the journey of The Odyssey.

The physical work that Mercedes Morán, the actress, did to portray this character with Parkinson’s was incredible. Mercedes, who is a friend of mine, never met my mother, who had that disease. When the movie came out, all my family—my children, nieces, nephews, cousins—said, “But did Mercedes meet Cuca?” — Cuca was my mum. Mercedes was identical to her, she did such a fantastic job, and that really moved me a lot.

Speaking of Buenos Aires, your novels are very focused on the city. Your long-time English translator, Frances Riddle, also lives there. Is that something important to you?

I think it’s important. I enjoy having Frances as my translator, not only does she know the city, but she also understands certain aspects of the idiosyncrasies of Argentines. She’s married to an Argentine and has an Argentine son, so even though she’s not from Argentina, she knows us very well. That helps a lot, especially with this novel, because there are many different voices.

I’ve been translated by people who don’t live in Buenos Aires who also do a good job. What happens in those cases is that they ask more questions. Frances has rarely asked me questions about the texts because she doesn’t need to—she already knows the details.

But even if someone hasn’t lived in the country, if they’re a good translator, they’ll find a way to grasp those nuances.

Thank you so much, Claudia!

Time of the Flies, translated by Frances Riddle, is out now with Charco Press.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.