Sebastião Salgado’s Amazonia: An Ode To Life

12 April, 2022Sunday afternoon. After entering the huge exhibition pavilion for Amazonia at SESC Pompeia, I closed my eyes and let the heat of over 30 degrees fall over me like a thick, wet blanket. And slowly transport me to the Amazon forests.

When I opened my eyes, I found myself surrounded by almost 200 images, the result of seven years of photographic expeditions through the Brazilian Amazon. I was hooked by Sebastião Salgado‘s unique vision. It is a pristine, exuberant, rich Amazon that reveals itself in front of our eyes.

The exhibition curator was very successful in her project of idealizing an environment in which the visitor would feel him/herself in harmony with biodiversity and forest peoples. Her design of allowing us to view the photographs from the same angle of their creator is fully achieved.

After all, it’s not just any curatorship: it was done by the person who probably knows him the most: his wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado. It is difficult to imagine the long journey of Salgado without Lélia, who followed the transformation of the economist who switched from calculating to photographing machines.

Right at the opening of the exhibition, one of the poles shows the Zo’é indigenous people [who you can read more about in Marcos Colón’s article, “Another Brazil Is Possible”]. For me, the highlight of the exhibition was getting to know the narratives of the Yawanawá, a people from the forests of Acre that were almost extinct in the 1970s, when their 120 members were showing very high rates of alcoholism, as well as social and cultural breakdown. They were literally wedged between the sword of the rubber plantation owners – who obviously did not want them united and strong to stand for their language, customs and, above all, land – and the cross of evangelical missionaries, who preached that their rituals were a devil’s thing.

The Yawanawá people began a remarkable process of rescuing their culture, leveraged in 1990 when the chief, Biraci Brasil Yawanawá, the Bira, said goodbye to the religious mission, re-establishing the teaching of their ancestral language and myths to the young people. Today, there are about 1,200 Yawanawás who move between the contemporary world, with their computers and smartphones like any of us non-indigenous, and their traditional world, cultivating among others their elegant works of feather art for which they are known. The history of the Yawanawá shows us that it is possible to unite both worlds in a sustainable way, respecting both human and forest nature.

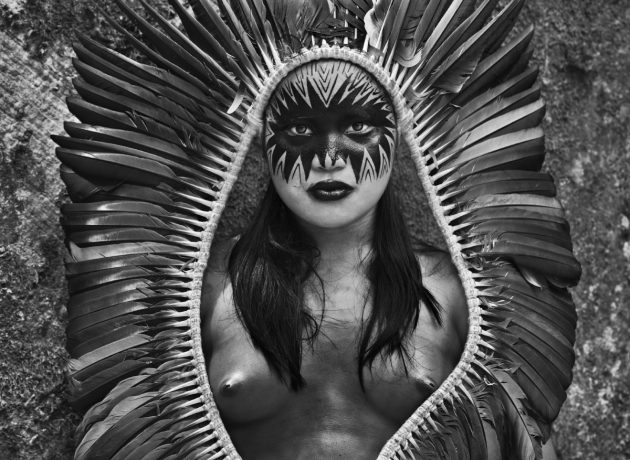

But what really touched me in the exhibition was the humanization of their characters. It is not a generic photograph of any “Indian”. It is the photo [pictured above] of the “Bela Yawanawá, from the village of Mutum, with a headdress and painted face”. Bela means beautiful, lovely in Portuguese. She is impressively beautiful. There is such a contemporary dignity there, and it is not about introducing an indigenous to a non-indigenous person, but simply one human being to another. Further on, it is not just another exotic photograph of a shaman interacting with invisible (to us) spirits, but “shaman Ângelo Barcelos (Koparihewë, which means ‘Chief of Song’ or ‘Voice of Nature’), from the community of Maturacá”, in action.

Upon leaving the exhibition, you feel that, despite the terrible news transmitted by the media – and which are equally relevant –, there are also possible paths in this struggle for progress with socio-environmental preservation. In short, in the best western tradition, good perhaps will triumph over evil one day.

About Sebastião Salgado

To understand Amazonia, it is advisable to know a little about Salgado’s trajectory. In 1979, after working for Sygma and Gamma photography agencies, he joined Magnum and began a trajectory that marked him as a great photographer of the human condition.

In 1999, he projected himself worldwide with the sadly monumental images of Serra Pelada, in the State of Pará, a living wound studded with men covered in clay that became known as the largest mine in Brazil whose exploitation took place mainly from 1980 to 1983.

It revealed Salgado’s keen eye for the global phenomenon of mass displacement of people, which resulted in the following exhibitions and books, Exodus and Children, published in 2000. In 1998 the Salgados founded Instituto Terra, a non-profit civil organization responsible for restoring pastures depleted by cattle ranching.

In 2015, the film-maker son of the couple, Juliano Salgado, directed with Wim Wenders, a documentary of his father’s work, The Salt of the Earth. Nominated for an Oscar in the Best Documentary category, its title is a gem in Portuguese, Salgado meaning salty.

At that moment, as the documentary shows, Salgado was being devoured by the images of death he recorded. As it could not be otherwise, the path of renewal and a return to life took place through photography. Amazonia is the proof.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.