‘Some of the Greatest Footballers and Journalists Talk as Though Pelé Never Existed’: Andrew Downie on the World Cup that Transformed Football

14 December, 2022As the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar reaches its final stages, Andrew Downie’s The Greatest Show on Earth transports us back in time to a previous era of football: the 1970 World Cup in Mexico. Artfully piecing together a mosaic from the recollections of players and coaches, Downie creates a vivid, entertaining picture of a tournament which seems a universe apart from the hyper-commercialised and exhaustingly mediatised spectacle currently unfolding in the Gulf.

The Mexico World Cup was a turning-point in modern football, broadcast for the first time in colour and with a better level of preparation and rationalisation than ever before. These changes mingled with the charm, mystique and (often laughable) amateurism which once characterised the world’s largest sporting spectacle. It is a fascinating mix, and Downie brings out well the euphoria, magic and occasional chaos which played out over three sun-roasted weeks in 1970.

More importantly for our readers, this tournament was one of the most fascinating and cherished events in Latin America’s sporting history, as Mexico asserted its national pride and capacity by hosting the world’s premiere cultural event, and Pelé’s Brazil enchanted a generation of global fans. We spoke with Andrew about a new era in football, conditions in Mexico, and one of the greatest football teams of all time…

Firstly, the book is great, and I particularly enjoyed how broad ranging your sources are. You do a really good job of talking to as many of the actors from 1970 as possible.

Thank you, that’s one of the things that I really wanted to do, to make it not just about Brazil, or England, or the Game of the Century, although these were really fundamental parts of that World Cup. I don’t actually remember the 1970 World Cup, but I do remember hearing about it as I grew up in the 70s and 80s, and I was aware of things like El Salvador and the Football War, Peru being there for the first time and Israel being there for the only time and how tough their voyage was. All that was as interesting [as the big stories].

And those huge moments are produced in the context of larger changes in the mediatisation of football. Audiences for the 1970 World Cup consumed it in different ways…

Yeah, so the 1970 World Cup was the first World Cup to be broadcast live and in colour, and I think that’s massive. It’s the first time people remember seeing a lot of these teams in colour, Brazil particularly with their famous yellow jersey which had always been in varying shades of grey from the black and white TV. I think that Brazil in particular and that World Cup in general really brought football alive to a lot of people. It also came at a time when football was on the cusp of changing from being a sport to a business. There wasn’t the FIFA paraphernalia you have today, with the team buses with the different slogans and the décor and stuff like that, none of that existed. It was just 11 guys that turned up for the World Cup, spent a few weeks training, often in some of the most laughable circumstances. They were there to play football really and that was it, and that comes through even more in hindsight, how pure an event it was.

You obviously spent a lot of time absorbing yourself in the context of 1970. When you compare that tournament with the one going on right now in Qatar, do you feel we’ve we lost something?

Yeah, for sure, and I don’t think that’s just happened in the last few years, it’s not just Qatar. I remember back in Brazil in 2014 when they banned Brazilian musical instruments – what is Brazilian football at the World Cup [without] samba? I remember the 1982 World Cup with samba bands playing in the stands and 1978 in Argentina with the teams running out to this enormous ticker tape welcome. You know, every World Cup was different, every World Cup had its own thing, and I think that was the case up until the 2000s, when it really became such a big business. And in 1970, it was identifiably Mexico, and you couldn’t confuse that with anybody else, and I think that we’ve lost that identity in football.

And why did Mexico want to host the World Cup in the first place?

Back then, as it is now, the Olympics and the World Cup was a way to present a country on the world stage as a modern progressive society which was the equal of Europeans and Americans. It was a way of saying that Mexico could put on the same kind of tournament as Europe, with the same flair and competence and grace. I mean, you have to say Mexico deserved to host it, it’s a football country through and through.

It really is, and the passion of the fans is clear throughout the book. Can you tell us a bit about their relationship specifically with the Brazil team?

I think the Mexican fans responded to the Brazilians in large part because they’re Latin Americans, but also, I think because they knocked out England and people didn’t like England at that time. There was a lot of ill will after 1966 and Sir Alf Ramsey’s comments about Argentina. England set themselves up to be disliked, they were closed off and didn’t mix, and the Mexicans jumped on that. You’re right, the dynamic between Mexican fans and the Brazilian team was quite special, they adopted them, really. That bond still exists today, and it’s really nice actually.

And that Brazil squad weren’t exactly the favourites going into the tournament…

No, when Brazil left for Mexico, they weren’t really rated. They had a great run in the qualifiers, but the last qualifier was in September 1969, and between their next game in February, there had been a lot of changes, which meant they struggled in their friendlies before they went to Mexico. One of the reasons they made the changes was because they were in a group with three European teams, and I think they were worried that they were going to come up against more physical sides. After 1966, Brazil realized that they needed to get stronger, they realized that they could be kicked out of the World Cup. Brazilians always thought, and still think that if it comes down to pure skill, everything else being equal, they’ll be the best team, but they realized after ‘66 that there’s more to football than just playing the nicest passes and the nicest dribbles. It’s also about stamina and speed and strength, so they spent a lot of time working on that in between 1966 and 1970. In particular, one of the real deciding factors was them preparing properly for the altitude, and FIFA singled them out in their report after the World Cup, talking about how they had prepared all this work with NASA scientists, done all this extra altitude training. They scored 12 of their 19 goals in the second half, and most of them came in like the last half hour.

You mentioned the altitude there, and that’s a constant theme of the book, can you tell us a bit about the conditions in Mexico?

The altitude was a big deal for all these teams. Most of them had never played in altitude before. Brazil, for example, had a little more experience because the clubs did a lot of tours in the summer, in the close season. So, the clubs had been to Mexico and knew what it was like. A lot of the other teams knew it was going be a struggle, but I don’t think they realized quite how much of a struggle. And then there was the heat, you know, the players weren’t used to 95-degree heat. I lived in Mexico and played football there. I remember playing my first game in Mexico, bombing down the wing and just about collapsing. You really do feel it.

The Brazilian team came to Mexico from a very difficult context. What was the situation like in Brazil in 1970, and how did that influence their public support?

Yes, so the famous AI-5 decree was passed by the military in December 1968 and that was the most draconian decree of the whole dictatorship: it closed down Congress and limited a whole bunch of freedoms. That was the start of what they called the ‘Lead Years’, for obvious reasons. So, in 1970, things were tough in Brazil, and when they won there was a real sense of relief. It was one of the few chances they had to go out, just this explosion of relief. In 1970 a lot of Brazilians had suffered over the dictatorship, and in the months before they said they weren’t going to support the team. Particularly in the first game against Czechoslovakia, because it was a Communist team, a lot of Brazilian leftists chose to support the Czechs, and when they scored, you know, they were waving their fists under the table and smiling behind their hands. But then Brazil equalized, and they all erupted, and I think they realised that the love for the Seleção was greater than any kind of political representation that they wanted to put on for a few weeks.

And obviously the main man in the Seleção was Pelé. You devote a long section to him and give a lot of space to players and coaches talking about just how exceptional he was and what it was like to play against him…

It’s all the more important now because people just talk about Messi and Ronaldo, or Maradona, and these are people who really, really should know better. Some of the greatest footballers and some of the most important journalists that write about sport talk about Messi and Maradona as though Pelé never existed. So, I thought it was important to get that section in with people talking about just how great he was, because I think an awful lot of people either don’t know or don’t care to know.

He wasn’t just a one-man team, though…

A lot of people see the 1970 World Cup as Pelé’s World Cup, and in many ways it was, but there are many players in that squad that have a much greater claim to being the best player at that World Cup. Gerson was hugely influential, and without Jairzinho’s goals they wouldn’t have won. Tostão opened the way for Jairzinho and Pelé, and Rivellino in midfield was superb. The defence gets a lot of criticism, but they held Brazil together, especially in that game against England. They all played their part.

That team was stacked with amazing players, but a lot of them didn’t have a huge profile in Europe before the tournament. You even have a great quote from an English newspaper calling Gerson and Rivellino ‘grossly overrated’.

That’s an illustration of how different the world was back then. People in Europe rarely saw Latin American teams or players. Occasionally these teams would come over, Santos would play in Europe, for instance. But it would only be the 50,000 people in the stadium who saw it, it wasn’t live on television, and you didn’t have clips on YouTube and TikTok and Twitter and all this. So, you were really going into the World Cup blind. You might have a scout who would go out and see them and England did play in Brazil in 1969, but that was it. You would see them at best once or twice every four years. And that was kind of why the World Cup was so magical at that point because it’s not like today where most of the players we’re seeing we know already because they play in Europe. Back then it was very different, you just didn’t know who you were coming up against. It was a whole different world.

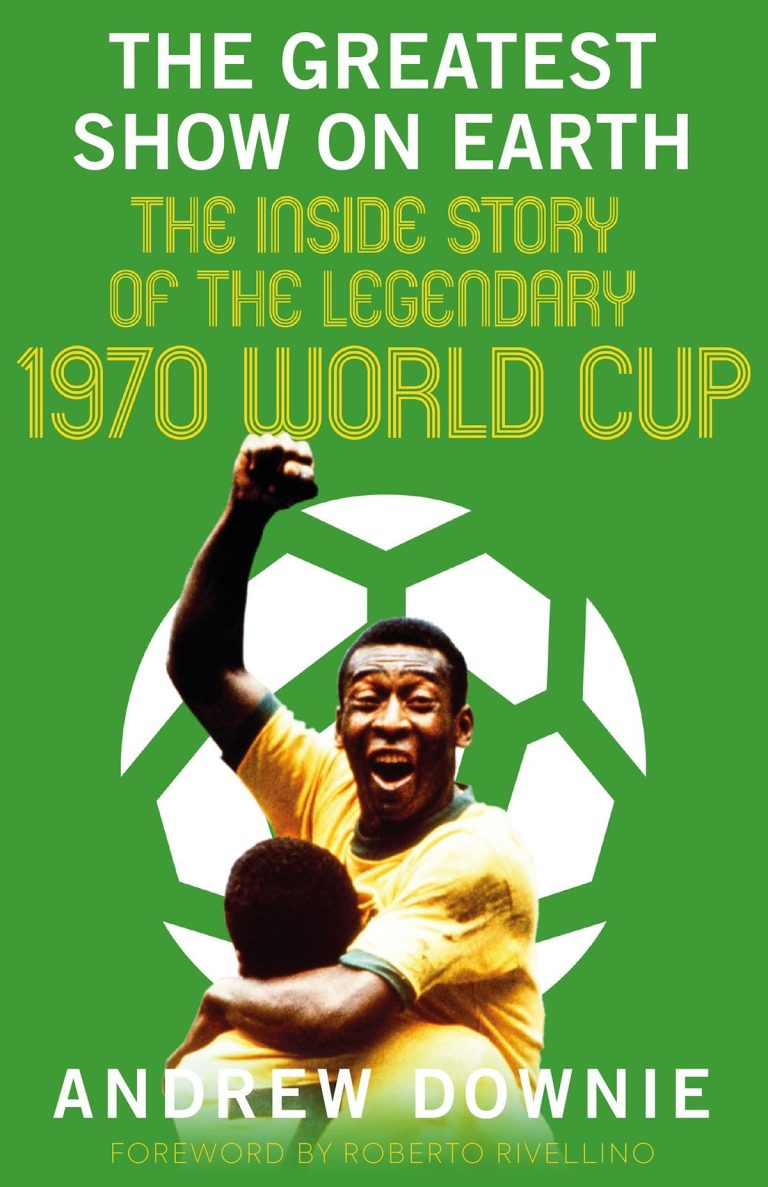

The Greatest Show on Earth: The Inside Story of the Legendary 1970 World Cup by Andrew Downie is available to buy here.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.