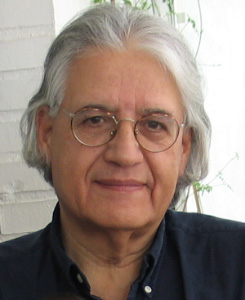

I Want Chile To Improve Through My Films: An Interview with Patricio Guzmán

21 October, 2019Patricio Guzmán is Chile’s most renowned documentary maker. His epic three-part La Batalla de Chile (The Battle of Chile) documented the rise of socialism alongside Salvador Allende’s government and its destruction under the steel fist of Augusto Pinochet in real time. His most recent film Cordillera of Dreams, remains true to a need to speak about the state of Chile and its fragmented society, through a similar holistic lens to that of Nostalgia for the Light and The Pearl Button.

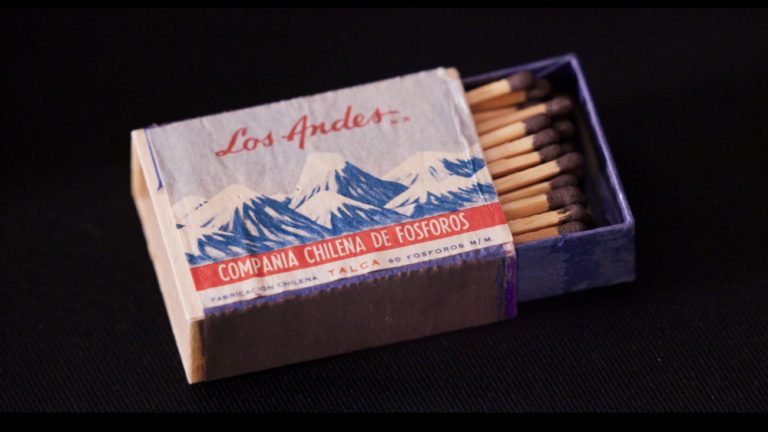

Guzmán analyses Chile through exploring its landscapes. This time, he chooses the vast Cordillera which covers 80% of the country yet has been neglected apart from in the national psyche. The Cordillera at once is a steadfast mother and a barrier isolating Chile from the rest of the world. Through interviewing locals in Guzmán’s birth city, Santiago, and including much of his own opinions and childhood experiences, Guzmán delves deep into the contradictory, backward state of Chile today and expresses, as always, his hopes for Chile to return to its childhood. Sounds and Colours spoke with Patricio and his producer and wife, Renata Sachse, during the BFI London Film Festival.

Your childhood features heavily in the documentary – we see your childhood home, you talk about your grandmother, about growing up in Santiago. Did this feel like the most personal of the trilogy?

Patricio Guzman: Yes, it was the film where I could tell stories about my childhood and my life before the coup, because there was space to do so. With only four characters in the film, there are moments where you can give a better explanation than the others in order to tell the story. There was space for me to talk about the same things, but from a personal perceptive.

Renata Sachse: I see it a little differently. His voiceover in the other films is narration. In this film it is his story, he becomes another one of the characters, making it a very personal film. It’s not an easy journey but he succeeded in this.

How did you choose your characters? What is your relationship to them?

PG: The first step in my scripts is to create imaginary characters. I narrate a story as if it’s already filmed and once I find what I want, I look for real people to fill those characters. I do a casting but I have no idea what I might actually find. It’s a long but easy process. And exciting.

Some of the characters were friends of mine, like Pablo [Salas, the cameraman], others I got to know while making the film. It’s very difficult to not feel affect for those you interview over a long period of time. So yes, the characters are all friends of mine, some of them new friends.

Is that the case with Jorge Baradit, the Chilean writer who you interview?

PG: Yes, Jorge is incredible, a magnificent writer and a wonderful character. His books are read by millions in Chile.

RS: It’s a very positive phenomenon. He’s young and bright and his books are selling like hotcakes. He tells stories that reveal secrets no one previously knew about Chile. He’s a bestselling author, all over the television.

…and he’s appreciated across all levels of society?

PG: Yes. It’s the first time a bestseller has been leftist, progressive. You can ask him anything, he’s very clever.

Pablo Salas, the cameraman who’s story dominated the middle part of the film, says he ‘could have done more’ during the dictatorship. Do you feel the same way? Is this one of the reasons you continue to make films about the dictatorship?

PG: No. We are both film-makers from the same country where the same things have happened, and we’re both interested in telling everyday stories, but Pablo is much more obsessive. Pablo has filmed consistently for 30 years. I filmed La Batalla de Chile over one year.

He lives as if the golpe de estado was yesterday and has done for 30 years, his life is filming, to him it’s like breathing. He’s much more committed than me. He wakes up, films. Has lunch, smokes a cigarette and goes back to film.

RS: I see an important difference here. Pablo is a film-maker who’s never made a film. It’s was very different for Patricio – there are images he wasn’t able to shoot as he was outside of the country. Patricio would travel to film, then return to Chile with the footage and put the film together. Every time he returned to Chile he would have an idea for another film. There are images he had to request from others in order to complete his films. What Pablo does is document. It’s a very different conception.

Pablo mentions youth in protests being less engaged but using their phones to document the marches. What is your view on Instagram culture? Will these videos be necessary memories of the future?

PG: I don’t know, it’s a great question, a great topic to explore. Asking youth what image means to them, if there’s a difference between living and presenting life in images.

In my time you had the camera, and in front of it, the world. It would be interesting to ask youth how they feel about their phones – what is it to you? What do you do with it? Is this your life or exterior to it? Do you use image to talk about yourself? It’s a fantastic topic. I haven’t covered it yet.

All of the artists interviewed in the film make art that reflects dictatorship. Do you think it’s possible for any Chileans to make art unrelated to the dictatorship in some way?

PG: It’s very difficult. Behind each person there’s a deceased parent, a relative who was tortured or someone who suffered. People were forced to change job, relocate, families fragmented. The golpe is so powerful and there are very few people who say they weren’t affected. It was an explosion everyone felt. Almost all Chilean documentaries today talk about the dictatorship in some way. And there are some fantastic Chilean documentaries and film-makers. It’s a bit different with fiction.

Do you see a glimpse of Chile returning to its childhood in the younger generation of Chilean film-makers?

PG: I express a longing for Chile to improve throughout my films – a hope that Chile will return to democracy, recuperate its maturity, a wondering if there hadn’t been a golpe de estado what Chile would be like as a country. One always has these hopes. Chile’s so small that it can achieve these things. There are some great film-makers and screenwriters at the moment, like Pablo Larraín and Sebastián Lelio.

This most recent film didn’t feature an indigenous Andean perspective. Was this purposeful?

PG: There are no indigenous people in the film. It’s made from a white perspective that doesn’t take notice of the indigenous population. I’m not interested in the indigenous issue. It’s a trap. It confounds the message of the film. When you bring an indigenous perspective, the film becomes about the conquest, about whether or not we’re European, about neglect. It will become a typical ‘indigenous’ film. And for me this is not significant.

There are other documentary makers who cover this, indigenous and Mapuche film-makers, but I don’t have anything to say about indigenous issues, I’m apart from it. It would be artificial. This is an auteur film – it’s my vision and opinion of Chile. It’s so important for documentary to speak from your own opinion.

RS: This film is not about human rights, it doesn’t cover all the statistics and tell everyone’s story. You can’t focus on so many topics and balance them all just so you don’t leave anyone out.

There are two photos we see at the film’s close. Who are these women?

PG: My mother and my grandmother. I don’t say anything but it’s an homage. They are important in my development, my education.

The Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña says ‘Chileans don’t want to know what Chile is about. It’s too painful. This is what the military coup achieved’. Are you challenging Chileans to break the spell of denial in this film and documenting Chile now for future generations to understand themselves? Who is the film for?

PG: My films are watched by 15,000 people in Chile – very few. 60,000 saw Salvador Allende. But in Europe I have 300,000 viewers. I don’t know how to get to more people in Chile to watch my films. Very few people go to the cinema to see documentaries there – it’s not like in France where there’s a taste for it. Many people don’t know who I am in Chile. It’s a very isolated country, there’s news that doesn’t reach Chile or that Chileans aren’t interested in.

Of course, there’s a pedagogical aspect in all pieces of art, especially documentaries, so I’d love for more people to watch them. The television is censored heavily by the government in Chile. Two of my films have been on television, but at 2am. The Minister of Education asked me for six films, they brought these to schools and were very satisfied. I made a box set of these films for universities. I’m not sure how many have seen them.

Jorge Baradit talks about the censored behaviour of Chileans and the country’s sadness due to being part of a system that goes against its nature. Your holistic style of documentary is different to those that shock to reveal, or others which narrate lineally. Is this a way in which you try to return to Chile’s ‘nature’ and avoid profit-driven techniques?

PG: That’s a good conclusion, it could be.

RS: Yes, Jorge says that the economic system imposed on Chile goes against its natural way of being – of people walking around the square, chatting with friends and acquaintances – it’s become closed and profit driven.

PG: I’ve made political films in the past like Salvador Allende and Memoria Obstinada (Obstinate Memory) and I wanted to change the point of view. I looked to the desert with its astronomers; the south and its water; I’ve used nature as a metaphor to open into subtopics. It helped me to put a story together. With each film I delve further into many aspects, and in the next film it’s even more profound.

Could you tell us any more about this next film?

PG: The next film is totally Chilean, but I can’t talk about it. It’s still a secret. It will follow the same style but go further, deeper. It will be estupendo (stupendous).

It’s an exciting process, writing and rewriting a script, preparing everything then leaving it and just going out there. You have to have a lot of guts. You prepare yourself and then you let your director’s intuition guide you and you progress freely on your own, for example in the South in the cold and the rain [filming The Pearl Button]. But it’s beautiful. You feel afraid, you don’t know where you are or whether anything will come. You feel a sense of failure then finally a light shines through.

The Cordillera of Dreams screened at the BFI London Film Festival. Six of Guzmán’s films, including The Cordillera of Dreams, will be screened at the Amsterdam Film Festival in November as part of a Retrospective.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.