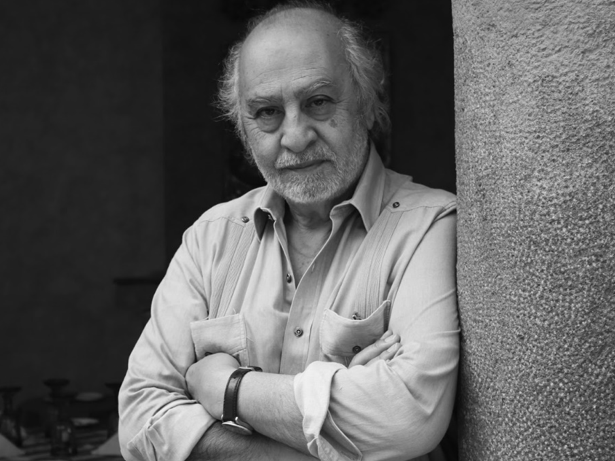

Miguel Littín and Chilean Cinema’s Social Outlook

01 October, 2020This article is by Simon Diaz-Cuffin (interview conducted by Isabel Aguilera, Ricardo Diaz-Cuffin and Simon Diaz-Cuffin) and is republished with permission from Alborada’s website.

The renowned Chilean director discusses today’s social movements, the COVID-19 pandemic and the relevance of his iconic film The Jackal of Nahueltoro fifty years after its release.

When the filmmaker Miguel Littín left Chile following the military coup in 1973, he was already well-known for his breakout hit, El Chacal de Nahueltoro (The Jackal of Nahueltoro, 1969), the true story of the life and imprisonment of José del Carmen, an itinerant and uneducated worker who murders the family that took him in. Confronting the injustices embedded in Chilean society, Littín’s feature debut critiqued the socio-political conditions that push people to commit these crimes.

On the back of this success, he went on to occupy the role of director of Chile Films, a state-run production company under Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government. During this period, he also shot the documentary Compañero Presidente (Comrade President, 1971), which compiled different interviews with Allende conducted by French philosopher and writer Régis Debray.

As the CIA-backed coup struck Chile in 1973, Littín was finishing his second feature film, La Tierra Prometida (The Promised Land, 1973), which would be completed in Cuba during his exile. Throughout his career as a filmmaker and writer, he has focused on recovering historical memory through culture, reviving an awareness of the past to serve the present. In Actas de Marusia (Letters from Marusia, 1975), his first film in exile and first Oscar nomination, Littín used the massacre of the saltpetre town of Marusia in 1925, when over 500 striking workers and their family members were killed, as an allegory of Chile at the time, with the military repressing any form of collectivised organisation in order to protect foreign economic interests.

During his years in exile, Littín worked between Mexico, Nicaragua, Cuba and Spain, expanding beyond Chile’s national landscape towards international contexts. During this period, he also established a relationship with Gabriel García Márquez, adapting his short story La Viuda de Montiel (The Widow of Montiel) in 1979. He also garnered his second Oscar nomination with Alsino y el Condor (Alsino and the Condor, 1982), set during the Nicaraguan Revolution, also in 1979.

In 1985, Littín returned to Chile disguised as a Uruguayan businessman to make Acta General de Chile (General Report on Chile), a four-part documentary series surveying the past-and-present Chilean identity of resistance. This experience subsequently inspired Márquez’s best-seller, Clandestine in Chile (1986), which applied further international pressure on Pinochet’s dictatorship. Littín inaugurated his return to Chile with his film Los Naúfragos (The Shipwrecked, 1994), going on to produce films like Tierra del Fuego (Land of Fire, 2000), La Ultima Luna (The Last Moon, 2005) and others. More recently, Littín released Allende in his Labyrinth (2014), which chronicled the president’s final hours in the Moneda palace, and is publishing his latest book Los Murmullos de la Ausencia (The Whispers of Absence, 2020).

Alborada spoke to Miguel Littín about his career, the recent protests launched in Chile and the longlasting impact of The Jackal of Nahueltoro.

To give us some context on your work, how did the relationship between cinema and Chilean society change during the 1960s and what is its impact today?

From the 1960s, cinema turned away from being merely a superficial and entertaining activity, without aesthetic, ideological or artistic stature. That is where my generation came in. In 1968, there was a complete turnaround and filmmakers started looking at their own country and wanted to interpret it. They linked themselves to Latin America, to other global processes of transformation and change, turning their gaze inward and trying to portray their culture from the inside, with the firm conviction that if we are capable of recognising ourselves, of seeing ourselves, we will also be capable of understanding our problems and facing reality to change and transform.

This also meant diagnosing reality and realising that the small minorities are those who have power, those who have resources, money and land, and that we have to overhaul and change society by looking towards the exploited majorities who suffer hunger, social injustice and governments dependent on what the United States orders and organises. We called this American imperialism at the time and it continues to affect the continent until today.

All the processes that came after, like the Popular Unity government, impacted the large majority of the country – workers, peasants and students – and gave them an approximation to the possibility of social justice. This included the arts, of course, which were no longer separated from workers, peasants or students, but instead were incorporated into their struggle and their development as a whole.

Then came the coup and we continued in our struggle, always trying to denounce the dictatorship alongside large majorities looking for a democratic solution, and this has continued until today. This generation of filmmakers has continued this tendency despite the fact that certain people have tried to distort its contents, accusing Chilean films of always talking about the same thing, that they always create problems but do not entertain or make people happy. Nevertheless, these filmmakers have followed a path, I would argue, where Chilean cinema is distinguished by its social outlook and its commitment to the needs of the majority.

When the social uprisings occurred in October [in October 2019], film was immediately incorporated into the struggle. People started to record through their telephones, taking into account the new technologies, recording with the instruments they had at hand and this left a testimony of the social explosion.

In your view, what happened with the social explosion in October? How has the pandemic affected this?

There has been an ideological crisis since ten or fifteen years ago which impacted Latin America very hard. Many governments have failed politically, even though they were governments of popular intention that rejected the right-wing but did not have any real solutions. Instead, the reforms they applied disappeared as quickly as they appeared. These governments left an enormous vacuum. And if the progressive sectors do not become aware of these failures, and do not make a profound analysis, we cannot move out of this crisis.

But I know very well that historical knowledge falls into the hands of the new generations and they are capable of taking the truth as a fundamental point, changing and transforming it. If we go to the problem of the plebiscite [on whether to change the 1980 constitution, drafted by the Pinochet dictatorship, with the plebiscite scheduled for October], I give it a great importance, I believe that it will be fundamental in the future, but it is not a solitary problem of today. One of the big problems for me during the protests is the lack of ideological clarity. There is a movement, there is a feeling, there is a forward march against the police, army and system but what do we want instead? More consumption? More? I would ask Chile, if I had the opportunity, what does ‘more’ mean? What is the rejection of this system of consumption that has us as prisoners of consumption?

I believe that it is absolutely essential to reflect in order to draw conclusions. Intervening in society does not only mean changing the means of production: we have to create different societies with different orientations. What was missing, it seems, was leadership and clarity to push forward the social energy of the uprising towards the goal of social justice.

The pandemic has turned humanity toward a global problem in which no-one has a solution to the problems of seeking and finding the solutions for a society established on the basis of greater social justice. Today, there is no vision of when the pandemic will end and what its consequences will be. Facing this uncertainty, it is very difficult to project into the future.

In your opinion, what is the relevance of your debut film The Jackal of Nahueltoro after fifty years?

I’m a little dismayed to think about the film’s relevance today from a social point of view. I have been to Nahueltoro, where I felt a deep contradiction between a social drama that ends in death and the tourist route to remember where the man killed and lived. But if the film is presented as a tragedy from beginning to end, following the canons of Greek tragedy, and it is the tragedy of a people, it is the tragedy of the deepest feeling of the soul, of identity, which is still present in the reality of the country.

From a social point of view, I can’t help but be a little desolate that it is still in force because the problems of the latifundio [the powerful landowning class] are still present. We have the problem, for example, of Monsanto seeds. Countries that produce agriculture become totally dependent on those companies because they have to buy the seed back from them again and again. So, the dependence is total, you don’t care anymore who owns the land, but it’s the big transnational corporation that owns the seed that’s going to use the land. The result is that man is dependent and not free to build his destiny. From that point of view, I see the film and I knew what I was doing, and of course I know why it is still relevant today. Now, is it hard for me to celebrate its validity? Absolutely.

The Jackal of Nahueltoro has been remastered for its 50th anniversary and is available to watch (in Spanish) through the online catalogue of the Centro Cultural La Moneda.

Miguel Littín’s Book Los Murmullos de la Ausencia is available for free (also in Spanish) through the University of Talca’s editorial page.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.