White Noise: Álvaro Bisama Lets History Speak

29 August, 2013In the mid-90s, my hometown of Clearwater got some national attention when the mineral-stained outline of the Virgin Mary appeared on the glass-panel front façade of a finance building. The hooded Virgin’s likeness took up nine meters of window pane, making it easily visible from the road. For a while, she was the town’s vibrant, prismatic Mother of God.

It wasn’t long before a group of the faithful began gathering each night in front of the building. A week in, the front door was so crowded with bouquet arrangements that each day a janitor had to stuff a trash bin with floral dedication. Rows of chairs were laid out in the parking lot, employee traffic diverted to the Kmart lot next door, and three afternoons a week, impromptu services were held with rebel priests from a diocese that refused to label it a miracle. At night parishioners gathered with candles in hand, singing hymns. After two months, with the faithful intractable in their intention to sanctify the twenty by twenty meter concrete lot, the owner of the building relented, selling to an Ohioan revivalist group. Bargaining on their faith, the faithful had prevailed, and reportedly at below-market value. The building became the Clearwater Church of the Virgin.

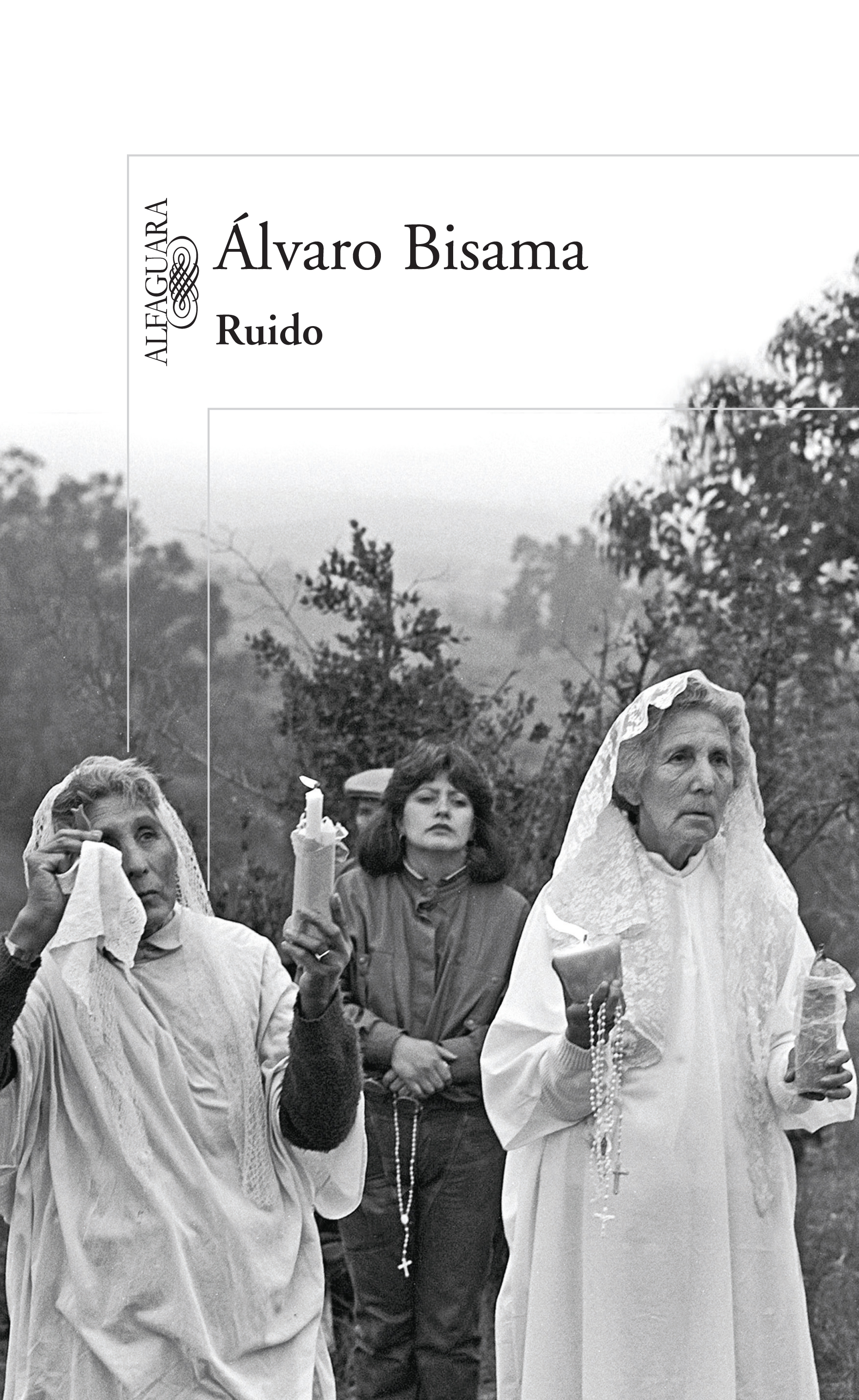

The difference between what occurred in a small Central Florida town in the nineties and what occurred in a small Chilean town in the mid-80s is that, in the latter, as Álvaro Bisama chronicles in his historical/documentary novel Ruido (English Title: Noise | Alfaguara, 2012), the Virgin was not content to take such a passive role. Mother Mary, through forces perhaps mystical, though undoubtedly political, had something to say to her flock.

Bisama, a literary critic/novelist from Valparaiso, imbues Ruido with a nameless, almost disembodied narrator, whose descriptions never stray from the third-person plural. We come to know intimately what is bred from rural life that exists somewhere between traditional agrarianism and capitalist modernity. The narrator’s hometown, Villa Alemana, is a small community once made up of only the elderly and children (i.e. a place where people either escape or never do), and now populated by techno fanatics and doom metal guitarists who have kids but also want to score drugs, and so wonder if there is anyone to watch their children.

Half-dead and half-living, like the hills that surround the town, the youth are trapped by the afternoon heat, in the narrator’s words, as well as by docudramas on TV, fantasies that have a beginning and end. They listen to AM radio with programs on UFOs and tango, stimulants from other countries or other galaxies, and stare at the ceiling waiting for something that will block out such ‘noise’, yet nothing does. The narrator puts it to us straight: the town, whose skeleton is merely the track that runs from the port to the capital, never changes. Nothing ever will. Even those that have brief respites, escaping to work in Valparaiso, inevitably return home in the evening. It is as if time itself had settled into one of the small adobe houses and there lived a contented, if monotonous, life.

Into this scene arrives another sort of narrator, nameless as well except for his ‘title’, the vidente, the seer. He doesn’t arrive out of nowhere; as a youngster the vidente is put into the town’s children’s home, essentially an orphanage. He is part of a group of youth without parents, who spend their days in church, in school, wrestling in the unpaved streets, without reference to a future and therefore without reference to a past as well. At the age of 14, around the beginning of 1984, he climbs Monte Caramelo and there he is first visited by the Virgin. For the next four years, the vidente leads thousands of people up the hill, goes into ecstasies, speaks in tongues, bleeds from the temples, and catches heavenly communion wafers on his tongue like snowflakes falling from the firmament. This is not poetic license, Bisama follows the real life story of Miguel Ángel Peblote, who indeed was labelled a prophet, supposedly conversed with the Virgin, and at one point had thousands of followers (there are a few Youtube videos if you’re interested). He also does not shy from the accusations that both the vidente and his buddies had an early teenage predilection to huffing that began just before the visions did.

Bisama’s interest in documentation, however, isn’t meant to go beyond the level of a good bar story. There’s no doubt he did plenty of research to write Ruido, but his narrator maintains a personal tone throughout, almost as if (and this may be true for many like Bisama that grew up watching this kind of thing on TV) he hopes the story of the vidente won’t compel people to make blanket judgements. How could somebody believe such BS, you may hear yourself saying as you read this, and Bisama’s response may be: well, not everyone does; here’s the proof.

In this sense the book is both valuable and, at times, frustrating. It may be just a coincidence that the first major protests against the Pinochet regime happened to coincide with the first visions of the vidente, but that kind of reasoning can be hostile to the novel form, especially within the rich magical realism tradition of South American fiction. Though I would by no means call Bisama an heir to that literary legacy any more than I would Bolaño, as the novel progresses, the supernatural and political start to coincide in curious ways. A better term for it might be magical history.

In real life, the Catholic Church in Chile had major problems with the Pinochet dictatorship’s human rights violations, though the two organizations were not outright adversaries. In real life, the Diocese of Valparaiso took the official position that the vidente was a fraud, and banned any priest within its ranks to perform services on Monte Caramelo. In real life members of the CNI (Chile’s CIA) visited the vidente, coming in black vans that ferried the faithful up the hill and populated the small town with uniformed soldiers carrying assault rifles. And in real life, just after the CNI became involved, the vidente began receiving messages from the Virgin that said that the Antichrist was the father of Masonry and Communism, that Russia would detonate a subterranean bomb, that the Catholic diocese must be dissolved.

Bisama directs all of these events, through his narrator, with an even hand. It is when he gives the latter free reign to contextualize those heady, hysterical days for him and his peers that we begin to understand just what the former means by ‘Noise’. The prayers that “vomited” from the speakers on top of the hill, hurting their ears; the hundreds of bronze fish being nailed to doors and walls around town, supposedly to save the people from the next major earthquake; and perhaps most interestingly, Pinochet’s visit to the town: walking slowly through the crowd, the dictator causes no pain nor joy, puts no-one into hysterics, radiates nothing but laziness and boredom. He brings, in fact, nothing but silence. And that, not the armed military, the threat of underground nuclear warfare or the coming Antichrist, was the real horror for Bisama’s narrator, the notion that one man with a “dirty-white pearl in his tie” could so completely shut off the both the anguished cries of the hopelessly faithful and the sardonic grunts of the hopelessly faithless.

The 18th century Italian essayist and poet Giacamo Leopardi, in his work Hopscotch of Thoughts, wrote of the pleasure of a “multitude of sounds, irregularly mingled together, not to be distinguished from one another.” Sound, in multiple forms, pervades the narrator’s understanding of life. It comes down from the heavens via the Virgin’s holy words, translated through the vidente. The followers of the vidente cry out, sing, pray and praise. And as the narrator grows up with his friends in the community, nearly all form bands, going from punk to reggae to ska, then to cumbia, and back again. The way Leopardi describes his pleasure of sounds makes one think, in this novel, that the pleasure of noise is just as fulfilling, when silence is the only other alternative.

The crimes of the Pinochet regime have been well-documented. In the 20 years of his rule, thousands of people were kidnapped, tortured and disappeared. Neoliberal economic policy via the “Chicago Boys” (that group of economists led by the late Milton Friedman) privatized industry in a way that, though labelled an economic miracle by the World Bank in the eighties, cleaved an ever-widening gap in a class system still pervasive today. Those dusty, hill-ringed communities where nothing ever happens, where no one seems to have a voice (and where the voice would, anyway, be absorbed by those hills or the great emptiness beyond them), suddenly disrupted by the appearance of the Virgin? There is, even in its hubris, a certain desperate pleasure in that.

Based on the history, it’s obvious that the idea of having a voice was a relative one during the Pinochet years. Some did, and some didn’t. Those that did, did the talking. Those that didn’t talked as well, but not beyond the reach of closed doors, at least until the mid-80s. Our parents made us promise to not repeat in school what we’d heard at home, Bisama’s narrator point out, but what force of will that takes! It’s almost better not to hear anything at all.

However, Bisama is determined to let his narrator speak not just for the faithful on the hill, but for his own generation as well, and here the novel loses some of its power. Too much discussion is made of the various members of his peer group writing songs, joining bands, getting popular in Valparaiso, getting more sophisticated, then falling into old habits. It’s an obvious metaphor, and too literal: one generation finds themselves in the music, the noise, they create. It is as if Bisama wants to document what wasn’t reported on national TV, or co-opted by the regime. But Ruido, at its best, is a novel about how events coincide with people’s lives without them really understanding it, and the varied racket that conflict produces. Sealed off in their underground culture, the narrator and his pals become a disjointed contrast to the faithful on the hill.

By the end of the Cold War, the vidente’s fame and relevance had foundered. He began drinking heavily in his twenties, and eventually decided to change his sex, taking on the moniker the Russian Princess. She was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver in her thirties and though still attracting a small but loyal following, and still receiving visions, she died in her home. She maintained, until the end, that she would resurrect. There is to this day a chapel on the top of Monte Caramelo.

It is a fact of modern life, with technology, 24-hour news, the internet, that the noise never seems to end. The Berlin Wall fell in 1991, and with it the craze of global Communism. However, come the turn of the century the world entered another epic of the clamouring, the noise loud but the voices diminished. Our Virgin Mother in Clearwater never made a peep. In the hyper-noisy world of modern life, one wonders if a form of silence will ever come again.

Ruido is published by Alfaguara in Chile and is available on Amazon Kindle

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.