Comuna 13: How Medellin’s Most Infamous Community Reinvented Itself

05 March, 2018Graffiti, art and music are bringing the community closer together. The beautiful mural above by @Chota_13 is emblazoned with the phrase “We’re transforming ourselves”.

Recently I went to Comuna 13, once labelled the most dangerous community in Medellín, Colombia due to its astronomical homicide rates and forced displacement of thousands of residents. I was taken around Comuna 13 by Daniel*, a 27-year-old local and resident hip-hop artist. Walking by myself with Daniel*, it was easier to access parts of the barrio not usually accessed by outsiders.

Given that Medellín was considered murder capital of the world in the 1990s, to say that Comuna 13 was rough is an understatement. As well as explaining the neighbourhood’s tumultuous past and how the community has been deeply marked by the conflict, Daniel explained how art and music have been woven into Comuna 13, rejuvenating the barrio, and bringing hope for the future.

Today, residents are no longer afraid to leave their homes.

Today, residents are no longer afraid to leave their homes.

About Comuna 13

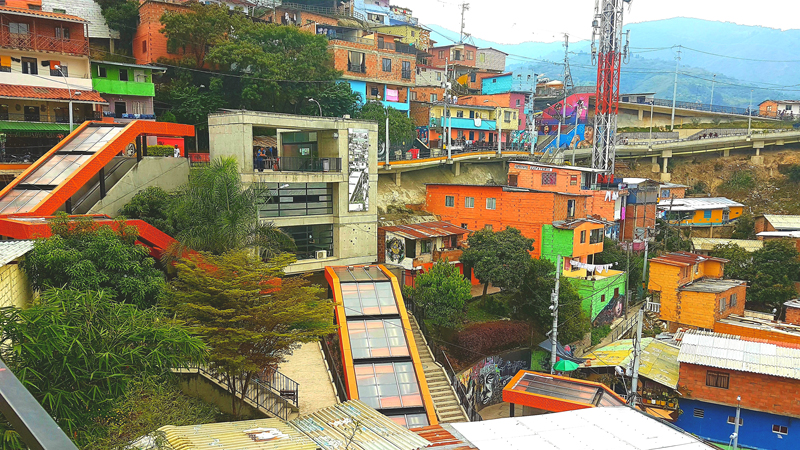

Comuna 13, also known as the San Javier, is an over-populated and low socio-economic neighbourhood that hugs the hills to the west of the city. Thousands of brick and cement homes with corrugated metal roofs are splayed, heaped together, with the occasional splash of greenery bringing visual relief.

Comuna 13 was renowned as an important centre for guerrilla, paramilitary, and gang activity. Situated close to the main San Juan highway, the community’s location is ideal for illegal activity, providing easy transportation of drugs, money and guns.

In recent years, Comuna 13 has become famous for its powerful graffiti murals which depict the conflict experienced by the barrio, corruption and the impact of state intervention, and the strength and importance of community action which helped bring an end to the violence.

Daniel said “our history is painted all around us – we’re proud of what our community has achieved”.

This powerful mural by @YesGraff shows the impact of the violence on the local community

After meeting me at the San Javier metro station, and a short bus ride later, Daniel and I began walking through the streets of the barrio. Along the way Daniel introduced me to several of his neighbours and friends, who were kind enough to share some of their experiences with me.

Only five minutes after entering Comuna 13 we met Jorge*, a man in his late 60s, whose eyes spoke of prolonged suffering. I noticed that he had a limp and was climbing the hill with difficulty. Daniel quietly told me after we’d said goodbye that he’d been not only tortured by narcotraffickers in the 1990s, but he’d also been injured in the notorious 2002 government raid, Operation Orion.

Nothing could have brought home faster the fact that here is a community who are living everyday with the consequences of being caught up in protracted conflict.

Comuna 13 is overcoming its difficult past and now attracts tourists from all around the world who come to view the amazing graffiti

Daniel and I pause at the lookout at the top of the hill, providing impressive views of the bustling, sprawling city below. Daniel began speaking about what it was like growing up here.

Why was Comuna 13 so violent?

During the 1980s and 90s, much of Medellín was controlled by groups loyal to Pablo Escobar, the infamous resident drug baron. Crime remained rampant even after his death in 1993, as drug cartels sought control of the region.

During the 1990s, Comuna 13 was actually one of the least violent areas in Medellin, with a homicide rate well below the city average.

The left-wing urban militias, the Armed People’s Commandos (CAP), the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and National Liberation Army (ELN), took control over the strategic entry and exit point of the city. Daniel told me of one occasion that he’d got on the wrong side of the guerillas in 1999, aged 9 (he didn’t want to say what for), “They dunked me and two friends in cold water, stripped us to our underwear and left us tied to a lamppost overnight”.

Much to Daniel’s further embarrassment, his mum came to get him in the morning, shouted in front of everyone that he’d been completely stupid and dragged him home in disgrace.

Daniel told me that, “when I was growing up, the Comuna was full of ‘invisible borders’, and that to cross one, even unintentionally, could result in your death”. He remembers seeing dead bodies on his way to school, and said that during his childhood his family rarely left the house in the evenings due to fear.

According to Colombia Reports, “while Medellin’s average homicide rate had been steady around 170 per 100,000 inhabitants around the turn of the century, the homicide rate in the Comuna 13 tripled between 1997 and 2002, going from a relatively low 123 to a staggering 357. In that same period, forced displacement went from three cases to 1259”.

This moving mural by @Chota_13 depicts the pain and suffering shared by the community

So what changed? In 1999, the right-wing paramilitary United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC) initiated an offensive to remove the left-wing armed groups from Comuna 13. They wanted to control the neighbourhood for the import and export of weapons and cocaine.

The resulting conflict between the guerrilla and paramilitaries spiralled out of control and caused unprecedented violence in Comuna 13.

On the 16th October, 2002, the Colombian government, under Álvaro Uribe Vélez’s presidency, carried out the controversial Operation Orión, attempting to defeat all rebel groups in the area.

During the four-day siege, over 1,000 policemen, soldiers, and helicopters attacked the neighbourhood. Hundreds of innocent civilians were wounded, tortured, and detained, and multiple people were killed, including several children (the exact figures remain unclear). Many people are also still missing, unaccounted for to this day.

The conflict made it impossible for the wounded to seek medical attention, and the community reacted together in solidarity, waving white flags, calling for peace. With that decisive act, the fighting finally ceased.

@Chota_13 chose to portray elephants waving white flags in remembrance of how Operation Orion will live in Comuna 13’s memory forever

How has Comuna 13 been rejuvenated?

As well as collaborative community action, there have been several important projects initiated by the state over recent years. These have helped improve the way of life for locals, and reduce the level of crime.

In 1996, the metro cable car system opened as an extension of the already vital metro. It provided residents from all socio-economic backgrounds with ease of access to the rest of the city, improving relationships with the local government.

Families later received new roofs, houses and community centres as part of government initiatives to improve Comuna 13.

By 2012, a huge 384m orange-roofed outdoor series of escalators was completed on the steep slopes of the comuna. What was once an arduous 35-minute hike, became a swift six-minute ascent, dramatically improving quality of life for locals.

For residents like Jorge with mobility problems, the escaleras electricas have brought a new lease of life

How Creativity has helped bring the Comuna to life

The walls of Comuna 13 have become a canvas to depict its difficult past, bringing hope to the residents, and recent a steady stream of visitors. Art and music are used as vehicles for political and creative expression, and as a means of expressing local anger and discontent with the violence that occurred in 2002.

Daniel introduced me to @YesGraff and @Chota_13, the latter one of the most renowned artists of Comuna 13. Chota told me “I often use elephants in my work because they have the longest memories. Our community will never be able to forget the violent conflict we’ve experienced“.

I asked YesGraff and Chota where they get their inspiration from, and Chota replied, “A lot of my work speaks of the strength of our community. I often feature a large pair of eyes because all experience enters through the eyes – no one can hide what they have experienced if you look into their eyes”.

Comuna 13 now hosts graffiti competitions and festivals that attract collaborations of artists from all over Latin America.

A local man gazes down at one of @Chota_13’s beautiful murals

Moving forward: hope for the future

Today in Comuna 13, local’s quality of life has changed for the better and they are no longer afraid to leave their homes. As Daniel and I walked through the narrow streets, the atmosphere felt relaxed with lots of kids playing on a football pitch emblazoned with the phrase “We reject any form of violence”, and vendors selling, among many other delicious dishes, their signature green mango ice cream topped with lime and salt.

Graffiti, art, music and state investment in infrastructure have helped achieve a sense of pride and reconciliation in a neighbourhood still scarred by guerrilla, militia and state violence.

However, as with any real change, a complete transformation of the neighbourhood will be slow, spanning decades. There’s still work to be done. Colombia is a country of resilience, and no neighbourhood embodies that characteristic quite like Comuna 13. If you’re visiting Medellín, I would highly recommend a visit. Comuna 13 has a tumultuous past, but a bright future.

*names have been changed to protect the identity of respondents

All photos by the author.

Emma Saville is the Senior Researcher at PositiveNegatives. She has written two books, Human Trafficking as a Weapon of War: Sudan a Case Study and Women and Machismo in Santiago de Cuba: A Failed Gender Revolution?, Her article, When Human Trafficking Becomes a Weapon of War, discusses the first of these publications. She tweets at @Emma_M_Saville.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.