Defining Cumbia with ‘El Libro de las Cumbias Colombianas’ + Classic Cumbias Mixtape

27 October, 2020What is cumbia? A musical genre? A dance? An event or celebration? A rhythm? In truth, it’s all of these things and more. It has been more than a decade since electro-cumbia spread across European dance floors and interest in the genre’s original form once again ignited. After its initial heyday in Latin America from the 50s through to the 70s, it seemed like it had finally found a form that would stick outside of its home continent, finding a place amongst other tropical and/or migrant musics, largely thanks to its fusion between local and global, rural and urban.

In Latin America there are a variety of sounds, dances and instrumental formats that each country calls cumbia and claims as its own. We also know that, despite regional differences, cumbia has become the backbone and the sound matrix that brings together followers from the south to the north of the Americas. Finally, on a local level, in the case of Colombia as the birthplace of this genre, we find that there is a great proliferation of music called “cumbia” which could just as easily be called porro, cumbión, puya, gaita or mapalé – the term “cumbia” in that sense has become a catch-all term for many rhythmically-linked genres.

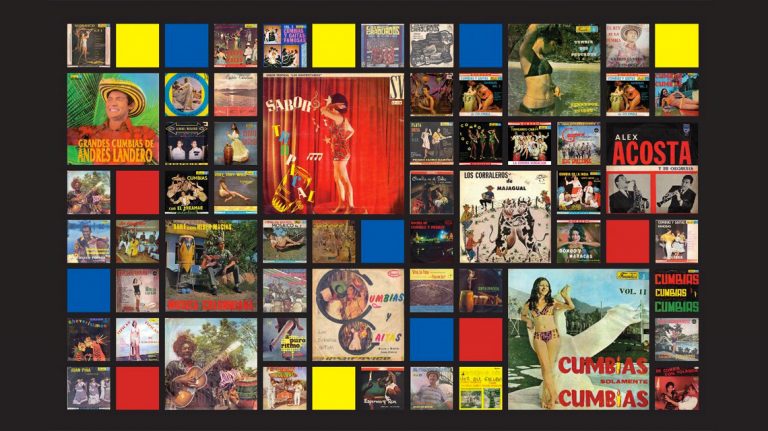

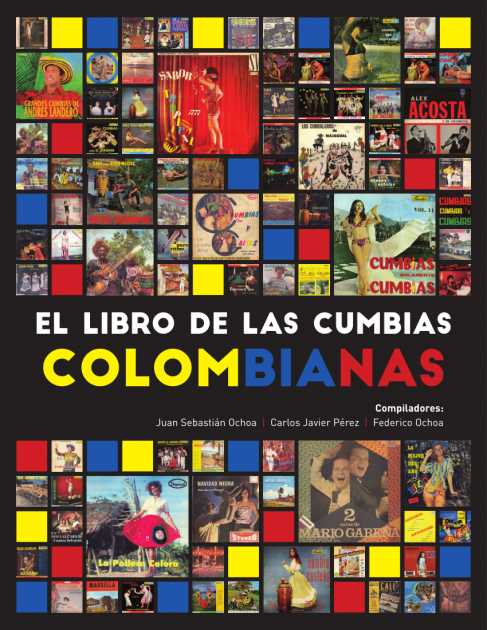

The book El Libro de Las Cumbias Colombianas (2017), compiled by Juan Sebastian Ochoa, Carlos Javier Perez and Federico Ochoa, highlights the need to formulate the question of “what is cumbia?” in its plural form: ‘The cumbias’ and not ‘the cumbia’. The book aims to give an account of the heterogeneous and complex “musical universe” that in Colombia is called ‘cumbia’. In first place, it suggests a repertoire of 90 Colombian cumbia songs that, especially throughout the history of recordings in Colombia, could be considered the cumbia canon. To do so, it proposes a categorization into three major types of cumbia that differ mainly in their instrumental formats: cumbias de flauta de millo (cane flute cumbias), cumbias de acordeón (accordion cumbias)and cumbias de orquesta (orchestral cumbias). Although the gaitas largas (large flutes) are central to the imagery of traditional cumbia and the ancestral discourse about it, songs with these main instruments are not included in the book for a simple reason: traditionally, the instrumental format of gaitas largas interpret rhythms such as gaita, porro, merengue and puya, but not cumbia. In second place, the book seeks to document this repertoire with a transcription of each song in lead sheet format scores along with discographic, aesthetic, and contextual references. It could be said then that we have a first Real Book of Cumbia.

Although there are sources that prove the existence of the term ‘cumbia’ before the 20th century, it is necessary to emphasize that at that time it was not used in the same context: it referred mainly to a dance closely linked to the music. It was from the 1950s, and as a consequence of the boom in the recording industry that the name ‘cumbia’ began to be used to label a ‘musical genre’ and differentiate it from others in the exploding music market. According to the authors, in 1963, Colombia ranked sixth in the world in terms of the number of records sold in relation to the population. Many of those records were also produced in Colombia by record companies that dedicated their productions to music of the Colombian Caribbean and, thanks to their great success and growing demand, the golden age of tropical dance music and, of course, cumbia happened. In fact, the corpus of selection for this book is Carlos Javier Perez’s personal collection of more than 15,000 records focused mainly on tropical music produced in Colombia during the 1950s and 1960s. So, within such an exuberant sample as this, how is it possible to select ‘only’ 90 songs?

As the authors want to make clear, the intention of this book is not at all to determine the borderline between what is and what is not cumbia, since, although it would seem to be a simple challenge to resolve turning to specific musical knowledge, in the practice many ambivalences and contradictions are found. The book rather proposes to select THE cumbias that are considered as most relevant because of their impact and recognition above all for the public, collectors or avid listeners. In other words, consensus is one of the main selection criterions. Furthermore, after going into detail on the main musical aspects of the three types of cumbia, and listening carefully and transcribing the 90 selected songs, the authors reveal to us some common elements that could help an untrained ear to recognize a cumbia:

- The binary subdivision of the beat and a moderate tempo, slightly syncopated rhythm with emphasis on downbeats and upbeats.

- Sober lyrics that reflect a certain serenity. This is clear when we take into account that an important characteristic of Colombian Caribbean music is the playful character of its lyrics, sometimes with double meanings.

- Also regarding the lyrics, many of these songs tell us about the practice itself of cumbia: how and where it is danced, which instruments there are and how they are played?

- The self-referential character of the cumbia. Many names of songs include the term “cumbia” and it is very common to hear a “cuuuuuumbiaaaaa” at some point in the song. By doing so, the genre is made explicit and, although it’s not something we can blindly trust to determine whether a song is cumbia or not, it provides an element of authenticity.

In the introduction, Juan Sebastián Ochoa states that this book is “anachronistic”, because “it addresses in the 21st century a typical need and attitude of the 20th century”, that is, the folklorist attitude trying to analyse, categorize or normalize musical practices. In fact, although a lot has been said about cumbia, there are few works dedicated to its rigorous analysis and to deepen the knowledge about this music. And although this book does not intend to solve this gap completely, it is undoubtedly a good motivation for further musicological researches. Also, this book may be of great interest to musicians, as they can find in the transcribed scores a guide, regarding the most relevant aspects in terms of melody, harmony and form. It is also of great interest to collectors, selectors, fans and music lovers who want to know more about the time and space, aesthetics and anecdotes surrounding the discographic production of these classic cumbias.

Finally, after having avidly read this book and listened to the proposed selection, here is a small personal practical exercise: a “selection of the selection”, a playlist of 20 from the 90 songs in Las Cumbias Colmbianas. Of course, the result depended mostly on the availability of those songs in my own collection, but also on the personal and collective experience that makes me consider them as my favourites. I allowed myself to include, as an intro and an outro, two cumbias de gaita larga, since this sonority is indispensable to immerse oneself in the magical world of cumbia. We have listened to these songs over and over again, in their original, electronic, fusion or reinterpreted versions; but nevertheless, they still echo and bring us to dance. Hope you enjoy them!

What are your 20 favourite cumbia classics?

Tracklist:

0 Tierra de poetas – Los Gaiteros de San Jacinto (Not in the book)

1 El millo se modernizó – Los gaiteros de San Jacinto

2 La Rebuscona – Pedro Ramayá Beltrán

3 Santo Parrandero – Cumbia Soledeña

4 Cumbia campesina – Los Corraleros de Majagual

5 Cumbia costeña – Alejandro Durán y su Conjunto

6 La pava congona – Andrés Landero y su Conjunto

7 Marbella – Pedro Ruiz y su Conjunto

8 Reina de cumbias – Conjunto Miramar

9 Mi Cumbia – Lucho Bermudez y su Orquesta

10 Yo me llamo Cumbia – Leoner Gonzalez Mina

11 Navidad Negra – Pedro Laza y sus Pelayeros

12 Noche de Estrellas – La Sonora del Caribe

13 La piragua – Gabriel Romero

14 Cumbia del Caribe – Edmundo Arias

15 Güepa je – Edmundo Arias y su Orquesta

16 Cumbia sabrosa – Clímaco Sarmiento y su Orquesta

17 La Nena – Juan Piña y sus Muchachos

18 Cumbia en Do menor – Lito Barrientos y su Orquesta

19 Cumbia de Sal – Los Falcons

20 Esperma y ron – Los Guacharacos

0 La cumbia – Gaitas y tambores de San Jacinto (Not in the book)

Find out more about El Libro de Las Cumbias Colombianas

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.