Don Ca

25 May, 2014The documentary Don Ca, from Colombian director Patricia Ayala Ruiz, is ostensibly the story of one man, sixty-year old Camilo Arroyo, who has spent a large part of his life living in the town of Guapi on Colombia’s Pacific coast. As the only white person in a town entirely comprised of African-Latinos, Camilo arrived as a young man to integrate himself into a community situated in a region noticeably divided along racial lines. His tale is an interesting one, but the film’s main strength lies in a largely unspoken socio-political commentary which is interwoven throughout striking imagery and a strong central narrative. What unfurls is an enveloping document of distinct aspects of Colombia’s social fabric which is by turn uplifting, critical and ominous.

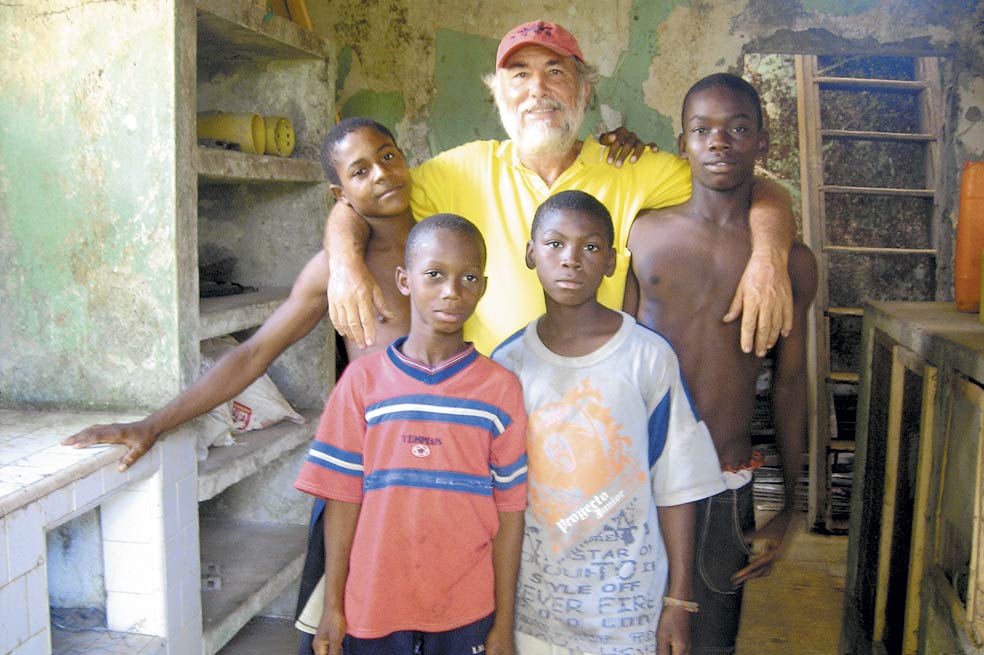

Having come to Guapi as a 24-year old, Camilo is a well-known member of the community and at ease among his fellow residents. He spends much of his time working on his house and land amid the sweltering regional humidity, while also seeking to contribute to the greater good as and when he can. A major part of this is achieved by taking in a number of boys who are either orphaned or have been abandoned by their parents, and his relationship with them is another key feature of the film. His has a strong bond with the boys, addressing them as men and giving them roles of responsibility, and the rapport he shares with fifteen-year old David and seventeen-year old Jaime is one of mutual respect and affection. The boys’ welfare provides Camilo with a sense of purpose, as well as necessary help around the place, and he in turn gives them stability, guidance, and a home. It ensures that their relationship easily avoids the potential suspicions of an aging man sharing his home with vulnerable youngsters.

These scenes make for largely positive viewing, and the early stages of the film contain an optimistic warmth that manifests in simple but happy images of the boys happily leaping off a pier into the river or, even better, a monkey stroking a kitten. Yet dark and dangerous realities soon become apparent: the threat of violence lurks in the shadows and Guapi is subject to frequent visits from heavily-armed soldiers or paramilitaries. Drug trafficking and political upheaval have turned the region into a tensely-inhabited combat zone and while the violence has so far largely bypassed Guapi, the menace remains.

It is the contrasts depicted in the film that give Don Ca its overall depth and a tone of conflicting emotions. The idyllic natural beauty of the region is at stark odds with the hi-tech military presence, as soldiers packing huge assault rifles come into contact with scrawny, bare-chested townsfolk. The most marked feature of Camilo’s relationship with the likes of David and Jaime lies in the irrelevance of the obvious differences between them. Then there are the rooted discrepancies of Colombian society. When Camilo heads back to his home city for Easter, the total segregation of the region is plainly clear. In contrast to Guapi’s African-Latino population, the only black faces here belong to some of the soldiers participating in the semana santa processions. It is a universal segregation that speaks of intolerance and disharmony, giving further context to Camilo’s life in Guapi. As he explains, he was largely accepted into the community as the locals ‘needed someone from another culture to speak for them.’

While many of the film’s qualities arise from the subtlety with which it addresses key themes, it is as much in what it overlooks that make for its biggest criticism. As the protagonist of the title, Camilo obviously features throughout but I would like to have heard more from the boys, particularly David, whose one granted time alone with the camera sees him divulge how to deal with armed men entering the community to help themselves to petrol, machinery, food and so on: let them take it or die. It is a brutally simple explanation of survival and emphasises the challenges faced in the region. But there is little by way of background detail regarding the boys. How did they come into Camilo’s tutelage? What does their future hold? The individual circumstances of David, Jaime and the other boys warrant further exploration and by omitting this in order to focus on the sole white person, Ayala leaves the film open to a charge of downplaying its black participants. After all, this is a film that essentially observes the African-Latino experience through white eyes.

Aside from this criticism, however, Don Ca both captivates and alarms, and pointedly addresses themes of race, violence, masculinity and duty. Camilo is by no means morally unscrupulous, yet he provides a strong central mast around which other aspects of the film can emerge, even if they are not as fully expanded upon as they may have been. It ultimately lacks the scope to fully scrutinise the social complexities that are raised but as a piece of observational filmmaking this is a deftly constructed work, and one that opens a portal on several distinct and thought-provoking aspects of Colombian society.

For further information, check out the Don Ca official website.

Don Ca will be screening as part of the Colombian Film Panorama taking place in London, Paris and Barcelona in June 2014. More details at colombianfilmpanorama.tumblr.com

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.