Héctor Abad Faciolince – El Olvido Que Seremos

24 September, 2018“It is one of the saddest paradoxes in my life. Almost everything I have written has been meant for somebody who can’t read me.”

Héctor Abad Faciolince’s El Olvido Que Seremos (published in English as Oblivion: A Memoir) is an arresting book one simply cannot put down. Part personal memoir, part biography of his father, part novel about Colombia’s violence, the sheer magnetism of the confessional first-person auto-biographical narrator attracts the reader’s undivided attention from start to finish.

The author’s father, Héctor Abad Sr. (1921-1987), was a Colombian doctor and academic who taught epidemiology at the University of Antioquia. His strong belief that health was a social and political issue was his justification for taking students to some of the poorest neighbourhoods in the city. He wanted them to see in the flesh rather than in textbooks the very real consequences of poor nutrition, lack of vaccinations and polluted water. In one of the book’s most glorious lines, Héctor Abad Sr. defines himself as “Christian in religion, Marxist in economics and a liberal in politics.” It was his Marxism which flagged him up as a potential threat in the eyes of right-wing groups, whereas his political liberalism encouraged persistent criticisms from the hard-left. Navigating this rocky middle-ground route in a highly polarized Colombian context populated by left-wing guerrilla groups and right-wing paramilitaries was undoubtedly of great intellectual courage. His life-long struggle for social justice through the design of preventive health policies eventually grew into public denunciations of the right-wing government for their constant violation of human rights during the 1980s. Unsurprisingly in this context, Héctor Abad was tragically murdered by two sicarios in 1987.

Twenty years after the event, Abad Faciolince produced this heartfelt novelized biography of his late father, which is also a carefully designed radiography of the violence which engulfed Colombia in the period. Yet the pain of writing such a novel is visible at every stage of its process: “I draw out these memories from within, as one gives birth, as one removes a tumour.”

Broadly speaking, the book is divided into two main parts. The first is an earnest portrayal of family life in the Faciolince household, where Héctor, the only boy, has five sisters. The male bond is perhaps one of the reasons which explains young Héctor’s unconditional devotion to his father. When his dad was away for work, he would go to his bed just to smell him. Indeed, their physical expression of love was mocked by young Héctor’s friends at school. In an Antioquia pervaded my machista cultural norms, Héctor Abad’s caring and sensitive nature was reason for scorn. This constitutes the first gender reversal in this idiosyncratic household, which, as eminent novelist Mario Vargas Llosa has eloquently put it, “it is such a lovely family one wished it were his own”. The second reversal is that Héctor’s mum is actually the main bread-winner in the house, having created her own management company. This, in a way, is what allows Héctor Sr. to be such a vocal critic of the government without worrying about the financial consequences of losing his job.

As Ernesto Calabuig has suggested in El Cultural, an evident risk of such a narrative is the slippery slope towards a sugar-coated, sentimentalized portrayal of a loved one. Yet Abad Faciolince treads this precipice without ever tumbling. His language is devoid of poetic flare; its plain simplicity attempts to recover these long-hold memories in as specific a manner as possible. The unmitigated love for his father is conveyed through anecdotes rather than concatenations of adjectives. Most importantly, the author vividly portrays his dad through the lens of a young boy, rather than a nostalgic superimposition into the past. This first part is perceived through the eyes of young Héctor as convincingly as To Kill a Mockingbird is presented from the point of view of Scout. However, the real narrative talent is evident when Abad Faciolince combines this perspectival narrative viewpoint with meta-fictional reflections from the older author in a seamless, rather than a truncated, manner.

The second part contains two tragedies which mark the family: first, the death of one of his sisters (sixteen year-old Marta) to cancer, and second, the murder of his father. The poignant description of Marta’s slow deterioration constitutes one of the most moving pieces of narrative I have encountered in recent years: “The past and present of my family were split with Marta’s devastating death, and the future would never be the same again for any of us.” Though not explicitly stated in the book, these deaths might not be unconnected, since Héctor Abad Sr. declares that if one is going to die, better to do it for his own beliefs: “If they kill me for what I do, would it not be a beautiful death?”

Forced to retire in 1982 after turning 60 years old, Héctor Abad Sr divided his spare time between gardening and participating in the media in defense of the government’s victims. This increasing visibility as a vocal critic of the regime that denounced the numerous cases of desaparecidos transformed him into a target. A leaked list to a radio station on 24th August 1987 announced that Héctor Abad was going to be murdered. His response was that he felt proud to share a list with other many notables figures he admired. The next day he was killed. In his pocket a hand copied version of a poem by Jorge Luis Borges was found, whose opening verse gives this novel its title.

In his laudatory review of the book, Vargas Llosa describes it as his most enthralling experience as a reader of the past few years. It is unsurprising that these two prominent Latin American novelists concur given the thematic similarities in their thinking. In his non-fiction articles in El País, as well as some of his novels such as Historia de Mayta or Conversación en la Catedral, the Peruvian Nobel laureate often produces scathing criticisms towards fundamentalist points of views, both on the left and right of the political spectrum. Abad Faciolince’s description of his father could easily be applied to Vargas Llosa himself: “He saw all kinds of fundamentalism as pernicious, not just that of believers, but also that of non-believers.”

Verdict: The intimate confessional nature of this memoir, in combination with its gripping style and the vividness of its detail transform this novelized biography into a contemporary Latin American classic.

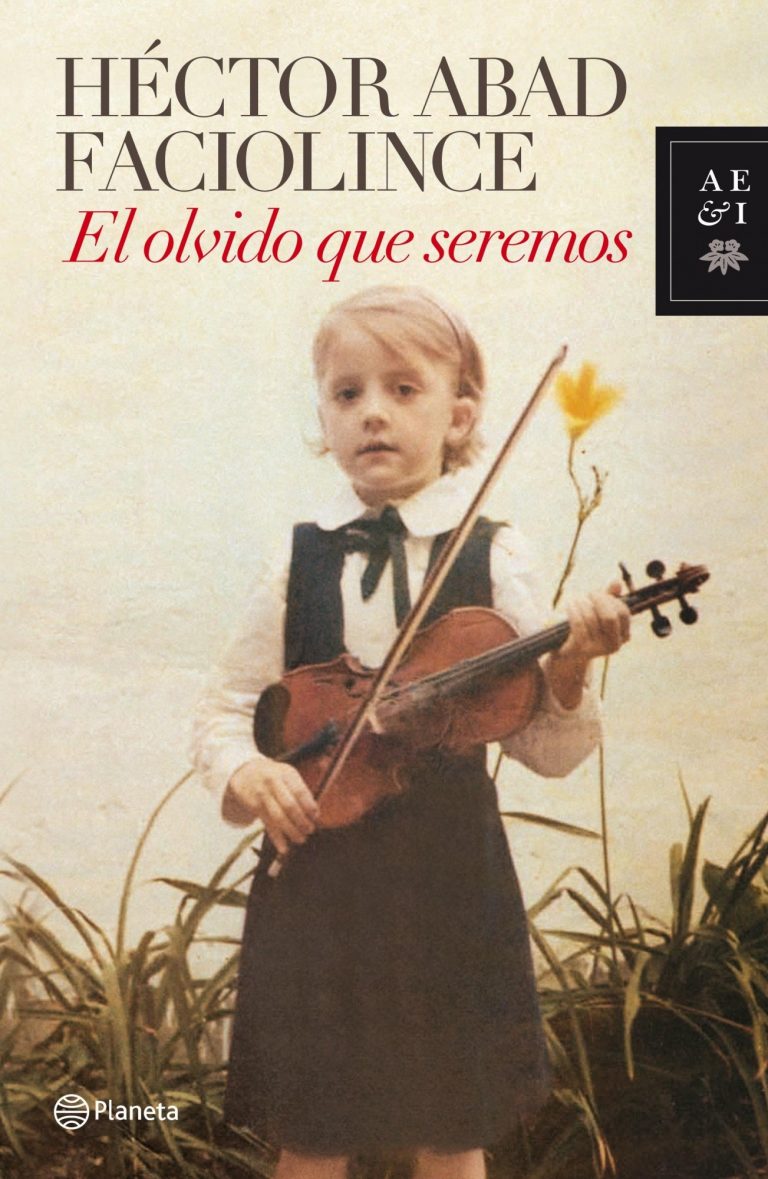

El Olvido Que Seremos was originally published by Planeta in 2006 and was recently republished by Alfaguara. It’s translated into English by Anne McLean and Rosalind Harvey as Oblivion. A Memoir.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.