In conversation with Juli Delgado Lopera: ‘Fiebre Tropical’, the Politics of Language and Representations of Maternity and Puberty

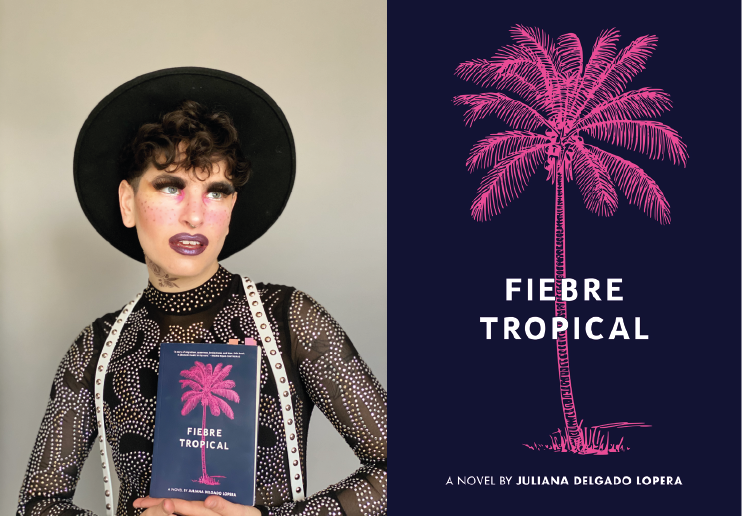

05 January, 2021Juli Delgado Lopera is a queer performer and writer. Driven by activism, literary performance and language, they have recently published their first novel, Fiebre Tropical. The story follows Francisca, a fifteen-year-old girl who just moved from Bogotá to Miami. It is a coming-of-age novel that deals with questions of sexuality, heritage and identity.

I sat down for a chat with Juli about their debut novel, the inspiration they got from Spanglish and the women in their life, what it meant to immigrate right in the middle of puberty, and navigating queerness in a Latinx context.

Click here to read Julia Garayo Willemyns’ review of Fiebre Tropical.

You chose to write the book bilingually and the vernacular is very personal – it goes beyond a simple mixture of Spanish and English. I was wondering if you could walk us through this choice. Do you make the switch between languages at narratively significant moments or do you simply write like you think, switching into and out of languages when it feels natural to you?

The use of Spanglish is twofold. It’s both a craft choice and my own linguistic experience. So, in terms of my own linguistic experience, I’m Colombian, I grew up there, I moved to the States when I was fifteen and I lived in Miami. I spoke very basic English when I got to the States. The English that surrounded me was English that was mixed with Spanish. I remember I would write stuff down all the time, like the really creative ways people spoke and made stuff up. My own family, my grandmother, my mom, my aunt, didn’t speak any English so they would make up words and say things phonetically. When I moved to San Francisco it was a little different because the Spanglish there is more Central American, so it has a different feel to it. But this also expanded my knowledge.

I’m very attracted to orality, to this blending of languages, to the language of the street. Spanglish is not something you see written in journalism; politicians don’t speak like that. It’s to me a discarded language. It’s allowed to be spoken on the streets or among family, but it’s not perceived as serious enough for literature or journalism or politics. Because it’s a phenomenon that happens in the US, although I use a lot of Colombian Spanish, there are a lot of modalities and languages that come from other people. It is a mix of all of us that come together from Latin America in the States. Writing in Spanglish gives linguistic legitimacy to a lot of immigrants and it speaks to my own experience as an immigrant.

When it comes to the novel, I had already been writing in Spanglish for a while and it is the linguistic space my stories spring from. Francisca exists in a marginal state and the Spanglish also highlights that experience of in-betweenness. When I was writing, it had a lot to do with intuition and rhythm. What’s fascinating about Spanglish is you don’t have a grammar book for it, and you can’t really teach people how to speak it. It’s something you have to immerse yourself in to really. It also has a lot to do with rhythm and has a very strong connection to music. So, when I was writing the book, I was very focused on how it sounded. The Spanish really took the sentences to a different level.

One of the most interesting aspects of the narrative is how you deal with these moments of marginality or intersections of identity. Do you think these questions of identity Francisca grapples with go beyond what traditional coming-of-age stories explore?

I don’t know if I can say it goes beyond traditional coming-of-age stories. Francisca is not concerned with being an immigrant who is reacting to whiteness or the American world around her. And that is the immigrant narrative that has been thrown at me all the time, and it is a reality. We all have to deal with how our otherness takes space in an American context. That being said, I was just interested in her story. She’s a misfit and a kid and she’s in a new place.

The villains or antagonists in the story are all immigrants and mostly women. I didn’t necessarily seek out to write this, but it just happened to be that what interested me was this tight-knit community of Colombians. I wanted to be able to have immigrants in my story who are horrible people and who have full humanity. I think that often when you are part of a disenfranchised group, your narrative is expected to be exemplary and respectable, and I’m just really not interested in that. I wanted my characters to be able to be messy and bad. I seek to give them full humanity in my work. I don’t want them to just react to whiteness, that’s why there are no white characters or American people in the story. Francisca is just reacting to her own mother and her church and the people around her.

Almost all of the characters in the novel are women. Why was it important for you to focus on female characters and relationships?

I think I didn’t necessarily seek out to not include any men, but I grew up around lots of women. My mom has five sisters. My grandmother has five sisters. That matriarchal world comes easily to me. I think there is a lot of romanticisation of the matriarchy, especially when it comes to feminism, and, don’t get me wrong, I’m a feminist and I studied Gender and Women’s studies, but I wanted to explore the toxicity of the matriarchy. I am fascinated by how women, and especially Colombian women and the women I know, communicate, through gestures, silence, body language – the unspoken language women have. A lot of this comes back to this idea of women as fully fleshed out characters.

When it came to the mother and grandmother, I didn’t want them to exist only in relation to Francisca, which is how women are usually portrayed – in their relationships to others, either as mothers, daughters or wives. I wanted them to explore their own sense of self.

All the female characters are quite complex, especially the maternal figures. Are there any sort of specific stereotypes you were trying to combat?

When I write I follow a story. I didn’t set out to demythicise something about women or immigrants. I was just interested in this story of a girl who moved from Bogotá to Miami. All of these bigger motifs or themes take on a larger shape and I see that now but when I was writing it, I just wanted to follow the story. I hear you when you talk about breaking stereotypes and, while it’s not what I set out to do, I know I am working against the stereotype of the immigrant mother or grandmother that is benevolent and good. Those stereotypes were very much imposed on me and my family when we moved to this country, but, I’m tired of the same poor immigrant story where people have no agency over their lives.

I’ve realised that I’m just really interested in women. I really wanted these women to be the default human experience. Usually the default human experience is a white man and I wanted these failing immigrant women to be the default for once.

Focusing on the story itself, there is this moment when Francisca grabs Carmen’s leg and for a second it feels like it could develop into a love story, but quite quickly it turns back to Francisca and the maternal figures in her life. Something similar happens closer to the end when she meets Andrea. Why did you decide to explore unrequited love?

I wanted her to join the church in some way. She needed to have something to hold onto. Carmen became a figure of hope for her. She hated everything else in her life: she had just moved, the heat was horrible, there was the church, her mom, all these things were happening simultaneously. I wanted her to want something so much and get close to getting it but never really get there. You know, feel that deep longing, which I think people do a lot as teenagers.

I also wanted to explore what it means to be a teenager and not necessarily have a community. Kids now have Instagram and stuff, but it was different then. She has no point of reference for her sexuality. I think that Andrea at the end represents some of that hope but in a different way because Andrea actually sees her. Carmen is always teasing her. You know she’s into it, but she never says anything. Whereas Andrea is the first person who actually sees her. That’s why I decided to end with that. Francisca cries at the end and is able to let go and she finally has someone who sees her.

You mention the church and I think your treatment of religion is also particularly interesting; you neither condemn it nor praise it. There are obviously some homophobic moments but at the same time Alba’s experience with a nun is homoerotic. I was wondering if you could talk to the complex relationship between queerness and religion in the narrative, because it doesn’t seem to be clear-cut.

Yeah, you’re right; it’s not clear-cut but I think that sometimes that’s what things are like. There is a lot of space for homoeroticism in Latino culture for women. Carmen and Francisca are able to lay down in bed and hold hands. If they were two boys, they probably wouldn’t be able to do that.

Francisca also wants to belong. She has nothing else. She has no friends. The church is a place where she finds community and a sense of belonging. I wanted to complicate this idea of the church. It is homophobic, the church is fucked up, and yet it’s a place where she finds a herself even if it is distorted. I wanted to complicate it because the church does provide a sense of belonging and that’s what human beings need; we need other people and we need people who hear us and understand us. Francisca is constantly seeking that. She hangs out with her neighbour, Pablito, but doesn’t quite get there and there’s the cool kids at the pool she’s never going to be able to hang out with and then this church girl opens up space for her to be part of something. It’s funny because she believes in God but is pursuing and daydreaming about the pastor’s daughter.

My mom joined the evangelical church when we lived in Miami and I wanted to explore why someone would join such a cult-y thing that, to me, was destroying a lot of our family. I wanted to explore what it means to arrive somewhere that is completely alien to you and how the church can be the one place that opens its arms to you. There is a lot of religiosity in my writing because I grew up in an extremely religious context. Things were very Catholic in Colombia and then extremely Christian when I moved to Miami, so religion is something that is very much at the forefront of how I came into being, even as an extremely queer person.

When it comes to the nun and the grandmother, you know, she’s fifteen, it’s the 1950s in Cartagena, a coastal city in Colombia. I wanted to be able to explore what it meant to be a girl at that time who didn’t have the language to articulate her desire. When I look at my grandmother and some of my older aunts, I see a lot of women who married men because they had to, but the real connections they had were with women. I wanted to explore what it would have meant to desire something else without the language to articulate it. I have all these words for my body. There is a queer world that is palpable and real, and it has its own language. This wasn’t the case then. Not only does the grandmother have this desire for the nun but she’s also never really explored her own body, and that is because she can’t.

Specifically, when it comes to Alba, it seems like gender is also problematised in a subtle way and like you said there is no language for it, so the topic isn’t breeched directly. Was this something you set out to explore or did just happen naturally in the storyline?

It’s natural but it comes from my own interest in gender. I am the first person in my family to come out as queer, but I also know I’m not the first one. Queer people have existed forever. I wanted to be able to explore the intimacy, the secrets and the darkness. I think some of these women in my family may have had those moments of desire or of gender questioning but there was no support then. They all grew up straight and cis. It was just the way the world worked.

I wanted to carve spaces where these moments of gender otherness or other desires are opened up. Because I know women in the fifties, sixties, seventies were feeling this and yet there was no history of it in my family. I think it’s because there’s never been the structures to support this. I’m interested in this line of women who have had narratives imposed on them. This was also something that was imposed on me and I had to rebel against it to get to where I am, but I live in a different world and I have the structures that support me.

That’s all I have in terms of questions, but I was wondering if you had anything else you wanted to say?

One of the most important things to me and the biggest inspiration for the book is my grandmother; which is interesting because the grandmother in the book has a small role but has a very big impact on the girl’s life. This is similar to the role my grandmother had in my life. She spoke no English, but I would go to the grocery store with her and she would just talk to people and make up words and say all of this really weird stuff phonetically and she managed to navigate a world that was completely unknown to her. A lot of my love for Spanglish and storytelling began with her. She introduced me to playful creativity when it came to language. She didn’t care about being right, she just wanted to make us laugh. I was fascinated by her ability to be so creative and brilliant but also by the way people looked down at her. People were demeaning but I thought she was actually really brilliant. She was just trying to make sense of a world that was very different to her. This book and the birth of this book has a lot to do with her and her ability to navigate a world that was completely alien to her.

Fiebre Tropical is published by Feminist Press and is available to purchase at bookshop.org.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.