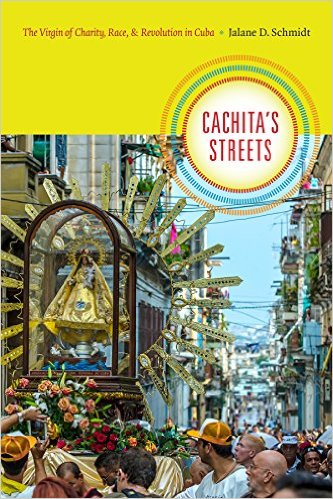

Cachita’s Streets: The Virgin of Charity, Race, and Revolution in Cuba

13 November, 2015Cachita’s Streets: The Virgin of Charity, Race, and Revolution in Cuba by Jalane D. Schmidt is an impressive history of Nuestra Senora Caridad del Cobre (Our Lady of Charity of El Cobre), the patron saint of Cuba. It charts the miraculous arrival of the Virgin in 1612, floating on the surf in the Bay of Nipe, Oriente, through the colonial period, the War of Independence (1895-98), US interventions (under the terms of the Platt Amendment, 1906-09 and 1912), the dictatorships of Gerardo Machado (1925-1933) and Fulgencio Batista (1933-1959), and on to the Cuban Revolution (1953-1959) and the present day.

The Three Juans

The finders of the Virgin were Indian brothers, Rodrigo and Juan de Hoyos, and a black slave boy, Juan Moreno. The story soon converted two Juans into three. This flexibility with the verity was not confined to the original devotees of this cult. Indeed, over time, the Virgin has had more colour palettes, depending on the pervasiveness of racism in Cuban society and ecclesiastical thinking, than a Bobbi Brown model. Similarly, she has gone from being the object of reverence to an almost exclusively black and mulatto population to becoming the patrona of all Cubans (Catholic or not), a symbol not just of piety and national identity but much more besides.

Regla Guys and Gals?

The idea of Afro-Cuban piety to a Catholic icon could only make sense to much of the Cuban establishment from colonial to modern times, if the Virgin were the subject of syncretism or else was an outright proxy for the characteristics or the personification of something originating in the Yoruba or Kongo Santería (aka Regla de Ochá or La Regla de Lucumí) or even Voodoo. In this interpretation, Catholic saints were seen as interchangeable with the orishas or saints such as Eleguá, Obatalá, Yemayá, Changó, and Ochún. The supposed correlate for the Virgin of Charity was the orisha/spirit, Ochún (the saint of fresh water, sensuality, flirtatiousness, female sexuality, love and fertility).

Culture, Identity and Nationalism

Schmidt does a thorough job of cutting through the back catalogue of racism, official duplicity and Catholic pragmatism and establishes a good case that the predominantly black (slaves and cimarrones, escaped slaves) and mulatto population of El Cobre, revered the Virgin as a Catholic symbol and not as something “other”. She achieves this by drawing on a rich array of historical and cultural sources (colonial and modern) including Juan Moreno’s original testimony rediscovered in the Library of the Indies in Seville in the 1970s.

The reality of Catholicism in Cuba, historically and in modern times, was that observation and participation were low among the exclusively white patrician class, the mulattos and the blacks alike. The difficulty for the Catholic authorities, as Schmidt points out, was to accord the same practices and standards to Afro-Cubans as it did to the Spanish-born or Spanish-descended population, particularly as the complexion of the population changed so markedly in late 19th century and early 20th century with the influx of settlers from the Canary Islands and Galicia, respectively. The mulatto population, the result of miscegenation, was similarly disparaged as the personification of a kind of louche feminised licentiousness, nowhere better exemplified than in the often raucous excesses of carnival or tourist-inspired travel posters.

Schmidt demonstrates quite effectively that Santería (aka Regla de Ochá or La Regla de Lucumí) and other African-influenced examples of spiritualism, were largely noticeable by their absence in Oriente, where devotion to the Virgin of Charity was at its strongest. Indeed it wasn‘t until the influx of refugees from Haiti (during its War of Independence from France in the early 19th century) and the arrival of slaves from West Africa in the late 19th century, that such practices were observed, and then they were mostly confined to the slaves who worked on the sugar plantations around Havana, Matanzas and in central Cuba. When slavery was abolished in the 1880s, these practices gravitated to cities of the west and centre. Oriente, remained owing to its isolation and poor transport links, what it had been for much of its history, a backwater. Its predominantly black and mulatto population in and around Santiago de Cuba and the mines of El Cobre, was long-established, dating back to the 17th century and was largely self-propagating.

Independence, Dictatorship and Revolution

Schmidt uses a neat quote from Arjun Appadurai, the contemporary social-cultural anthropologist, which tellingly summarises the nature of history, culture and much else: “Humans of course create objects. But objects may also be said to create humans.” From Cuba’s War of Independence from Spain (1895-98) right through to the present day, this frail icon has been used as a convenient instrument for social, political, cultural, racial and national evangelism.

To the revolutionary hero Céspedes and the mambises (revolutionaries) she was a talisman, to the dictators Machado and Batista, she was either disparaged as subversive to Catholic orthodoxy or else a convenient propaganda tool, to Castro she was a means to an end and thence surplus to requirements, and to the Catholic Church she was both Nuestra Senora and its best asset for self-preservation against a rise in Protestantism, Santería and Marxist-inspired materialism. When Jesus’ birthday was reassigned by Fidel Castro to Enrique Jorrín, the father of the cha-cha-cha, you can see why it acted as it did. Castro saw fit to ban Christmas for 30 years, banning all religious processions and replacing carnival with public proclamations and exhortations to the nobility of the worker. Religion is dead, long live religion!

Praise Be

After Pope Benedict XV made her ‘la patrona de Cuba’ in 1916, at the behest of petition by the mambises, she was the subject of a Canonical Coronation by Pope Pius XI in 1936, accorded the Papal bull Quanto Christifideles in 1977, by Pope Paul VI, who designated her shrine a Minor Basilica, crowned again by Pope John Paul II in 1998, awarded a Golden Rose in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI and enshrined in the form of a brass statue (a gift from Cuban bishops in 2008) and given her own special place in the Vatican’s gardens in 2014. Even Hemingway awarded his 1954 Nobel Prize, to the Virgin’s shrine at El Cobre.

What Schmidt’s work makes plain, aside from the Virgin’s evident meaning to the Cuban people as a national totem, is that people don’t take too kindly to being told what to think, say or do. The evident survival of the Virgin as a devotional object is in no small part due to the Catholic Church’s persistence but in essence this has been aided and abetted by the proscriptive and somewhat empty puritanical tenor of the Marxist experiment. No ‘New Man’ worth his salt would ever voluntarily forego carnival to listen to four hours of deadening rhetoric. Similarly, faith and spiritualism have been with us long enough now (Virgin of Charity or not) for there to be strong circumstantial evidence that man really can’t live by bread (or shopping) alone.

Cachita’s Streets: The Virgin of Charity, Race, and Revolution in Cuba is published by Duke University Press and available from Amazon UK and Amazon US

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.