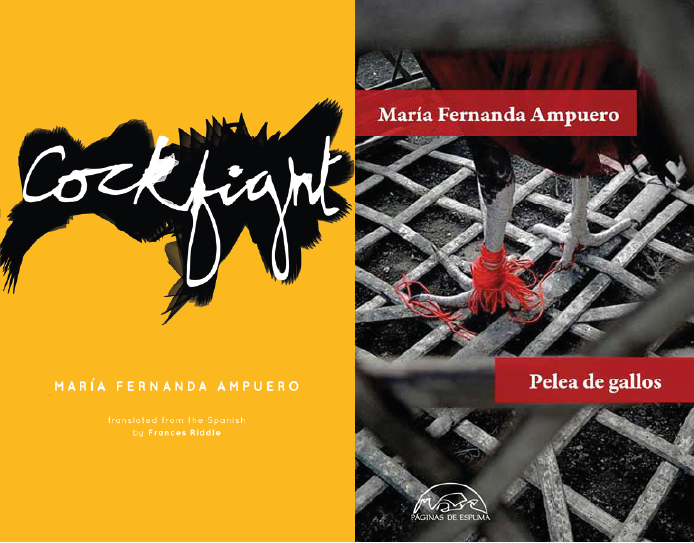

María Fernanda Ampuero Targets Family Violence in ‘Cockfight’

18 August, 2020Award-winning author María Fernanda Ampuero, leader of a new wave of Ecuadorian writers according to The New York Times en Español, bites again with her first collection of short stories, Cockfight. Not for the faint-hearted, this is a gory, gruesome collection of nightmares and fairy tales that coldly narrates the lives of contemporary Latin American women. Through sparing prose and exacting detail, with no time for decoration or pomp, Ampuero delivers timeless feminist fiction that packs a punch and sticks with you like tar.

The short stories begin from a child’s or a teen’s point of view, marking a loss of innocence and an often shocking introduction to the brutality of female existence in Latin America. “To be a woman is to be in the epicentre of violence”, Ampuero claimed in an interview at the 2019 Guadalajara International Book Fair. But in these stories, women are not only placed at the receiving end of such violence; they take matters into their own hands and liberate themselves through often crafty rebellions. After brutal scenes of gendered violence, we feel the victory of female emancipation. Ampuero’s characters learn to speak the language of violence, spitting out the dirt and grime they’ve been subjected to in order to loosen the apron strings and escape their gendered fate.

Cockfight unflinchingly offers a window into the home – “the most obscene institution that exists today”, according to the author. Only in the ‘comfort’ of the home can horrors still be silenced; only in the home is there still impunity for those in power and no hope for reparations. “It’s time to question this institution”, Ampuero insists.

Sparse prose accentuates the shocking contrasts within the domestic setting and there is an overarching sense that what lies behind closed doors is far more menacing: middle-aged women’s gossip proves fatal; young girls learn not to fear ghosts but to fear the living; no amount of money can buy domestic safety. Maids are present throughout the stories, appearing to have lived “four hundred more lives” than their employers and offering critical insight into toxic family dynamics. The domestic space is a distinct experience for each character, although it is clear that violence and misogyny cut straight through class and wealth diversity – marking everyone’s existence.

At times the tales are amplified by hyperbole, the storytelling magical but gruesome. Narcisa, a family maid, appears to have strong, masculine hands to the girls she looks after, “Her fingernails, long and pointy, could open sodas without a bottle opener”. At other times the narrative is bare and painfully relatable. A lack of decorative contextual detail allows the stories to speak to women all over the world, familiar especially to women across Latin America.

US imperialism quietly dominates the dark corners of wealth and poverty alike and incest reeks from most of the pages, as do the lasting effects of abuse in its many forms. Amongst the gore, rot and sordid sexual nightmares are stark critiques of the futility of faith, corrosive attitudes towards female pleasure, soul-destroying punishment of children’s curiosity and upper-class denial of mental health issues. Despite the shocking nature of these tales, there is still much to be read between the lines. Often they feel like fables that could apply to numerous lives and situations; some include an overt lesson and others end with a question.

Ampuero’s playful language is an intellectual respite in these grotesque tales of abuse, post-natal depression, human trafficking and servitude. Coro, a story that stuns with its wordplay brilliantly translated by Frances Riddle, pushes harmless gossip to its violent limits and exhilarates with its presentation of female brutality. Bleach contrasts the struggle of local life with the lonely luxury of a privileged holiday: “The bathrobe with the hotel’s golden logo feels like the fur of a polar bear, thick and downy, after bathing in a cold mountain spring.”

“ If we could see women’s pain in colour, if we could hear it in sounds; living in this world would be insufferable.”

A visceral attack on the senses, Ampuero’s Cockfight reminds us that the heart is a viscera too. She claims that these stories came from her entrañas, her guts, her deep intestines, her very being. These stories came from her own suffering and that of her friends, sisters, mothers, cousins. “If we could see women’s pain in colour, if we could hear it in sounds; living in this world would be insufferable”, she insists.

Born in Guayaquil, Ecuador, in 1976, Ampuero has published articles in newspapers and magazines around the world, as well as two nonfiction books: Lo que aprendí en la peluquería and Permiso de residencia. Her experience as a journalist, relating the cold hard tales of daily life, underpins her storytelling in Cockfight, Ampuero’s first short story collection and her first book to be translated into English.

Cockfight, translated by Frances Riddle, is published by Feminist Press and is available to purchase at Blackwells (UK) and Bookshop (USA).

Watch María Fernanda Ampuero’s interview with France 24 at the Guadalajara International Book Fair here (Spanish, no subtitles):

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.