Chavela

18 October, 2017The life of Chavela Vargas, the Costa Rican-born canción ranchera singer who spent most of her adult life in Mexico, unfolds in a spot-on eponymous documentary film by Catherine Gund and Daresha Kyi. Chavela recounts a life writ triple X large by the excesses of alcoholism, sexcapades, ravings and profligacy, conveying the turbulence and turnaround of a tortured soul. The film-makers have invited as witnesses an appropriate and stimulating set of supporting actors in the story of her life, as well as artists, such as Tania Libertád and Miguel Bosé, whom Chavela touched deeply with the emotionality of her songs and her story.

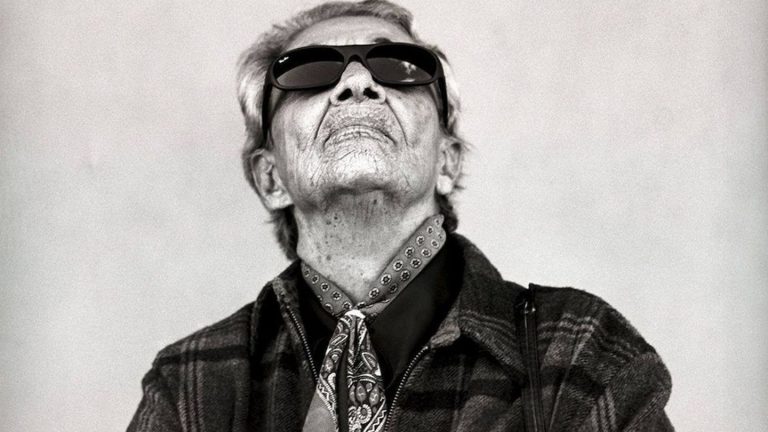

Chavela Vargas stands with Amalia Rodrigues, Billie Holiday, Maria Callas, Edith Piaf, and other women who extruded their suffering by developing magnificent instruments of vocal truth. Their’s is a raw pain that grabs the listener like a claw and doesn’t let go. In this tribute we see Chavela playing big stages and small; no matter the venue nor the time in her life, she chips away at our innards and gives us substance as well.

Isabel Lizano Vargas was born in 1919 in San Joaquín de Flores, Costa Rica. Growing up, she began to develop masculine-identified traits like the husky voice that would come to define her as she sang, and she eschewed little girl games and dress. Thus she was ostracized by her school and cohorts, called a niña-niño (girl-boy) and driven from her local church. Her family, too, withheld affection and attention, and when her parents separated, Chavela was abandoned and tossed about by various uncaring family members.

At 17, this self-proclaimed soñadora (dreamer) lived out her great dream: she escaped to Mexico where she began busking on the streets of the bustling, seamy, capital. Discovered there by ranchera icon, José Alfredo Jiménez, the two quickly bonded; he became her life, and artistic coach, bequeathing her with some of the most overwrought songs of a genre dominated by men and marked by passion, infidelity and loss. Chavela would come to possess, for example, “Amanecì en Tus Brazos” (I saw the light of day in your arms) and “El Ultimo Trago” (The last shot [of tequila is intended here]).

Jiménez opened up to Chavela the tavernas and boîtes of the city, where the rich and famous, and not so rich and famous, came to play and consume round upon round upon round of tequila. She took quickly to the crowd and their pleasures, and years of debauchery began, effectively precluding her rise to the more lofty halls of entertainment in Mexico.

Chavela is brightly lit by footage cut from a 1991 interview given at home to Ms. Gund and two other women, clearly taken by her and her story. In it, we see Chavela relaxed yet “on” all the while, a tough spirited and tough boned woman, (her profile, featured often as she speaks, is aquiline and awesome) who plays to the camera like a precocious child. Chavela dwells on her romantic life. She loved to be in love. This was another drug for her, a cocktail of devotion and rancour poured to the very lip of the glass, ready at any moment to spill over. Her affairs with women (she insisted that she had never, ever been with a man) were legion and included a tryst with Ava Gardner, a tumultuous 18 months or so with Frida Khalo (numbers meant little to Chavela, they were there to be finessed), and rumours of her carrying off young campesinas at gunpoint.

The account of Alicia Pérez Duarte, her partner of about three years, details the nasties of Chavela’s alcoholism, episodes of domestic violence, and her railings at those she loved. In lengthy reminiscences, Duarte seems to love her still, although they shared their lives during Chavela’s darkest days, as she spent over 12 years in drunkenness and obscurity. But she came away from them dry. Pérez Duarte claims to have given her lover an ultimatum in 1990 to which she acceded: you’ll not only lose me, but my children as well (whom she had grown to love) if you don’t stop. As Chavela tells the story, however, she was called into the hills behind Tepoztlán, where she was living, and cured after about a week spent with shamans there.

Dry now, she began performing again and was invited to Spain where she quickly fell in with Spanish cineaste Pedro Almodóvar. He had used a number of her songs in his films and seemed in awe of her when they meet. They shared a tender friendship until her death. Thanks to Almodóvar’s efforts, Chavela sang for the first time in a grand concert hall, the Sala Caracol in Madrid. It was her conquering moment: Spain was giving her the recognition that heretofore had eluded her in the demimonde of Mexico. She was able now to return, reborn and welcomed, to play the great halls that had been off-limits to her for so, so many years. With Almodóvar again her advocate, Chavela signed to perform at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City.

At eighty-one, esteemed now and free of her drinking and bad behaviour, Chavela came out as a lesbian. Of course her sexual identity had been an open secret: aside from the scandals arisen after she’d stolen away the sweethearts of many a powerful man, she refused all her life to change the gender of her signature rancheras, written in the masculine; her dress was characteristically “butch”; and her voice coarse and deep.

She was now ready to move on. One likes to think that she lived long, always looking for the redemption she did find towards the end of her life. She died at 93 after returning to Mexico from Spain. Fittingly, her memorial was held with masses of mourners outside, at the Palacio de Bellas Artes.

Chavela is a judicious film, one that, given its protagonist’s life, could easily have kicked up a storm of smut. But the film-makers were measured and objective, avoiding hagiography, yet remaining scintillating all the while.

Chavela is currently screening in select cinemas in the US and worldwide. See chavelavargasfilm.com/screenings for the latest screening news. The DVD will be released in January 2018 and will be simultaneously available on video on demand platforms, including iTunes, Amazon Instant Video, FandangoNow, and others.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.