Miguel Grau: The Gentleman of the Seas

10 October, 2012Wartime demands an insurmountable amount of sacrifice from those who are fighting it; so much so that enlisted men and women are scarred from the experience, whether physically, psychologically or, very often, both. Such intensity makes those who fight forgetful of their humanity, and implies certain heartlessness in times of war. But even in the darkest hours, there are those who can still remember to live honorably.

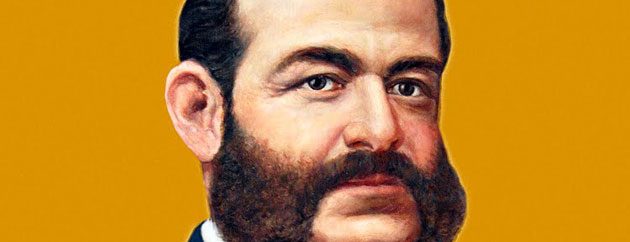

From 1879-1884, Bolivia and Peru waged war against Chile over a number of profitable provinces that the three countries shared. It was called The War of the Pacific and it was during this war that a tactful and chivalrous hero emerged: the Peruvian naval officer, Miguel Grau. Though he died prematurely at the young age of forty-five, Grau established a reputation for himself that lasts to this very day as El Caballero de Los Mares, or “The Gentleman of the Seas.”

Before I go on, I would like you to consider Grau’s nickname: being a gentleman is already a difficult task for most men. But Grau was able to do it in the midst of wartime, where he probably saw blood as much as he saw water. On top of that, he was in the navy, stuck on a boat in the ocean. Let me remind you that it is this kind of environment that inspired the simile, “to curse like a sailor.” If Miguel Grau was able to live in this state and still remain a gentleman, then it is no wonder he is so honored in his homeland.

Before he was given his famous moniker, Miguel María Grau Seminario grew up in Paita, a seaport city in northwestern Peru in the district of Piura. It was in Paita where Grau’s love for the ocean blossomed, due to encouragement from his mother. His maritime fascination led him to enroll in the Paita Nautical School, through which he had his first oceanic experience, travelling aboard a maritime schooner to Fortune, Colombia before he even hit puberty. And as though the fates were laughing at him, the schooner sank, and Grau had no choice but to return home. But the young man only saw it as a minor setback, and he continued his journeys by sea, travelling on merchant ships to America, Europe, Oceania and Asia. These early adventures made their mark upon Grau, and set the stage for a lifetime on the water.

By the time he reached nineteen, Grau decided to change his maritime course. He left his position as a merchant marine and enlisted in the Peruvian Navy. This militaristic choice may have been homage to his father, who fought alongside Simón Bolívar for independence from Spain.

With such passion for the water, combined with a strong spirit, Miguel Grau easily made his way up the ranks in the navy. He began as a military officer on a steamer, and then quickly received a promotion, travelling to Europe. While he was there, he oversaw the construction of ships for his country’s fleet, which seemed to promise even bigger and better opportunities.

Yet just like his first adventure on sea, Grau’s goals and dreams were cut short, and he was imprisoned a year after coming to Europe. The Peruvian government had made plans to hire a foreigner to control their navy, a move in which Grau and fellow officers refused to participate, leading to some time behind bars. Rather than seeing it as a nationalistic and dedicated stance, the Peruvian government feared resistance from one of its best officers. But as soon as Grau explained his choices in his trial, it was decided that his political choices were for a just cause.

Once he was released from prison, Grau became commander of the Huáscar, a ship that, during his stay in Europe, had been constructed under his authority. Grau was bonded to the Huáscar for the rest of his career in the navy, even to the point where the ship became his deathbed. It was at this time that the navy man’s career saw no obstacles, and his promotions remained continuous. Upon his return to his native land, Grau and the Peruvian Navy joined forces with Chile to drive out the Spanish, who were attempting to reconquer the lost lands of Latin America. The two countries eventually drove Spain off, and Grau’s tactile commitment and talent on the sea brought him another promotion — this time as Frigate Captain for the entire fleet of Peru.

Several years later, the Peruvian people elected Grau as congressman for the Congress of the Republic of Peru, where he represented his native area, Paita. Grau temporarily left the navy for this political career, but in time, he did return to sail across the Pacific. Despite his return to his original passions, Grau was able to leave his mark on congress, just as he did for everything in his life. To this day, congress calls Grau’s name during the beginning of each meeting, where every congressman and congresswoman declares the navy man “present.”

But Miguel Grau left the political life as soon as The War of the Pacific took form. The war had stemmed in the Atacama Desert, which Chile, Bolivia, and Peru all shared territorially. The desert was a valuable resource for all three countries, due to the fact that large amounts of nitrate had been discovered in the mines there. Though Chile was the country that actually ran the mines, they were owned by Bolivia, who imposed a tax on the Chileans. At the same time, a bond grew between Peru and Bolivia, which Chile saw as nothing but trouble. Chile was gaining large profits from the Bolivian mines, yet the taxes they had to pay caused resentment towards Bolivia. Along with the fact that Peru had been the center of the Spanish Empire, which allowed the country to remain profitable and successful over the years, Chile began to see Peru and Bolivia as a threat to its economic growth. Chile’s contempt became clear to both countries, and as a result, Peru and Bolivia signed a political alliance. Around the same time, Bolivia increased the taxes that Chile had to pay. These two moves acted as the straw that broke the camel’s back, and Chile declared war on Bolivia.

Had Bolivia been alone in the war, they would have quickly lost to Chile. The mines they owned were on the Pacific coast, and at that time, Bolivia was void of any kind of naval defense. But thanks to the alliance that Bolivia had signed with Peru, the latter country defended its ally, and took on full responsibility as the oceanic defenders.

As mentioned, Grau took to the seas once more in order to battle. Ironically, the last time that he had taken part in naval warfare, his country had fought alongside Chile; for The War of the Pacific, the former allied country was now his opponent. But Grau felt no hindrance involving himself in the war, and took command of the Huáscar once more.

Shortly after returning to the seas, it appeared as though Grau had never left them. Using Huáscar to its full advantage, Grau defended the coasts of Peru and Bolivia, and held back Chilean forces with agility, speed and strength. Chile had absolutely no success invading either country when Grau and Huáscar were on the seas.

But even in his success during wartime, Grau was a gentleman at heart, and during the Battle of Iquique, Grau revealed his strong character to both his home country and his adversary. In 1879, the Chilean ship Esmerelda created a blockade in Iquique, a Peruvian port. When the Huáscar arrived, Grau asked Esmeralda’s captain, Arturo Prat, to surrender peacefully; Prat refused. In Prat’s mind, Grau would destroy Iquique if he fired upon Esmerelda. Yet the Chilean captain made the wrong assumption, and as soon as Grau fired, Prat and his crew suffered immense damage. The Peruvian Huáscar suffered none.

Rather than realising that he should just cut his losses, Arturo Prat made a passionate speech to the still living members of his crew, encouraging them to never surrender. Being the honorable man that he was, Grau once again pleaded with Prat to surrender, and once again Prat refused. Shortly thereafter, Huáscar sunk Esmerelda along with its captain. Not all of the Chilean crew had drowned with their ship, and upon seeing so many men in the water, Grau ordered his own crew to save as many men as possible. Once they made it to dry land, the men that Grau had saved praised both him and Peru.

One could easily consider Miguel Grau a gentleman by this point, but the navy man still persisted in his kindness. Feeling downtrodden by the death of his foe, Grau wrote a letter of condolence to Arturo Prat’s wife, and did the same for all the Chilean men who had died in battle. He collected Prat’s belongings, and sent them to Prat’s wife, including the following letter:

“Dear Madam:

I have a sacred duty that authorizes me to write you, despite knowing that this letter will deepen your profound pain, by reminding you of recent battles.

During the naval combat that took place in the waters of Iquique, between the Chilean and Peruvian ships, on the 21st day of the last month, your worthy and valiant husband Captain Arturo Prat, Commander of the Esmeralda, was, like you would not ignore any longer, victim of his reckless valor in defense and glory of his country’s flag.

While sincerely deploring this unfortunate event and sharing your sorrow, I comply with the sad duty of sending you some of his belongings, invaluable for you, which I list at the end of this letter. Undoubtedly, they will serve of small consolation in the middle of your misfortune, and I have hurried in remitting them to you.

Reiterating my feelings of condolence, I take the opportunity of offering you my services, considerations and respects and I render myself at your disposal.”

Once Grau sent the letters and the saved Chilean men returned home, the Peruvian captain’s moniker was born, and he became “The Gentleman of The Seas” to Peruvians, Chileans and Bolivians alike. Grau’s nobility became renowned, and his stereotypical oceanic look — muttonchops and all — was legend. And even after all of his honorable efforts, even after the opposing country had given him his distinguished nickname, Chile focused all of their efforts on eliminating Grau. Though they considered him “The Gentleman of The Seas,” Grau’s naval prowess and talent far outweighed his generosity.

Several months after Grau earned his moniker, Chile sent their entire fleet to attack the Huáscar, eventually trapping it at the Punta Angamos. Despite all of his military and oceanic expertise, Grau and the Huáscar could not compete against the entire naval fleet of Chile. The Chilean ships fired several heavy-duty shells at Huáscar, one of which took the life of Miguel Grau. The crew of the Huáscar continued to fight, but Chile succeeded in the battle, and without Grau and his prized ship, Chile eventually won The War of The Pacific.

But such defeat could not shake the admiration that so many had for Miguel Grau. His home country has remembered him fondly, and honored him as much as they possibly could. Just about every district in Peru has a street with Grau’s name on it. In 1967, the Peruvian government posthumously gave Grau the title of Grand Admiral of Peru. In the year 2000, Peru’s people voted Miguel Grau “the most important figure of the millennium” in the country. Peru has even established a holiday for Grau, celebrating his legacy on the eighth of October each year, the anniversary of his death.

In short, if this legendary Peruvian has taught us anything, it is this: even in the most destructive settings, a gentlemanly attitude can have more rewards than one can imagine. Happy belated Miguel Grau Day.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.