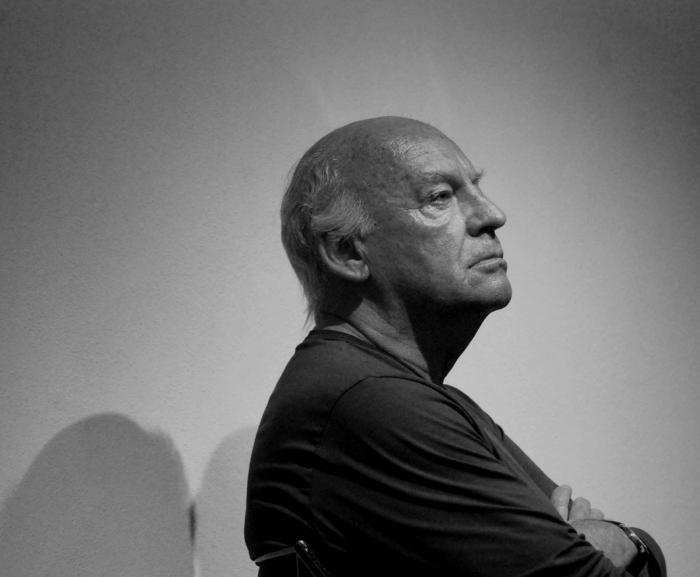

Eduardo Galeano Acknowledges the Weaknesses of ‘The Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent.’

10 June, 2014History and Eduardo Galeano have an intimate relationship. History offers Galeano timeless access to the scrolls that disentangle themselves across the planet for his perusal, yet the relationship is certainly reciprocal. In payment for this access, Galeano bears the burden of sharing this story: a continuum of voices and loves; of treasures found and mountains emptied; of secrets forgotten and memories made secret; of the waters, colours, and soil that shakes itself free and arrives somewhere else; of ardour, treachery and, above all, optimism. It is not that this task is the privileged prerogative of Galeano alone, rather he is simply one of the many who accept history’s offer to peer through her pages. This has allowed Galeano to view certain idiosyncrasies of history and our interaction with it – that history never says, for instance, “goodbye”, preferring instead to tantalisingly utter “see you later”; or, that, “because of the complexities of human nature, reality” – history’s cousin of the present – “can change.”

This was part of the justification that Galeano gave at the II Bienal Brasil do Livro e da Leitura in late April this year, when he publicly distanced himself from his most famous work The Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. “Reality changes,” Galeano said in response to a question about what the contemporary Open Veins of Latin America might be; “Time has passed, I’ve begun to try other things, to bring myself closer to human reality in general and to political economy specifically.” However, in contrast to those who feel that Galeano is renouncing and shaming his work and even leaving ‘the left’ in the gutter, I feel that, instead, he is acknowledging this book’s weaknesses and failings as a work of scholarship, while still believing the key tenets he witnessed, which provided the fuel to his passionate fire. As Galeano said in the interview, “…The Open Veins tried to be a political economy book, but I simply didn’t have the necessary education. I do not regret writing it, but it is a stage that I have since passed.” This self-criticism is well-founded, and similar criticism has before been levelled at the book. Ibsen Martinez, in a generally positive review of the novel and left-wing literature in general, suggests however that perhaps Galeano’s account may be too reductionist: “Mr. Galeano’s guileful writing may result in fascinating reading […] but history cannot be enslaved by our partisan opinions.” This book is not perfect – as nothing is. In my earlier review of it, I noted that there were some sections which were hard to wade through, and I feel that this is a manifestation of Galeano’s own self-admitted lack of necessary education (as well as my own inability to understand even the simplest economic terms!)

Nonetheless, it is important to note – especially in response to those who would like to suggest that the whole ‘Pink Tide’ movement toward the left, as witnessed in Latin America over recent decades, has now been undermined by the failure of one of its key documents – that the principle themes and ideals explored within Open Veins do not only exist within that book. This book is not pages fluttering in a void. There were many articles and books written beforehand and afterwards, including a number of very recent interviews, wherein the same arguments are fought. In Guatemala, País Ocupado (Guatemala, Occupied Country), published two years before Open Veins, Galeano vehemently attacks North American imperialism and their shadowy hands, fiddling with apparent impunity in the political situation of Guatemala. Perhaps even more importantly, in an interview in July of 2013, Galeano claimed, perhaps forlornly, that we suffer from “collective amnesia” which is “where we forget the injustices of the past.” Galeano advances, “It’s not a person [who is responsible for this forgetfulness.] It’s a system of power,” dominated by “the most powerful institutions, the IMF and the World Bank [which] belong to three or four countries.” Place a mirror up to this quote, and one sees reflected the following from Open Veins: “The international division of labor was not organized by the Holy Ghost but by men – more precisely, as a result of the world development of capitalism.”

Therefore, personally, I understand Galeano’s most recent comments on his book less as a rejection of the arguments he so passionately pursued and more as a process of self-criticism and analysis. As a man whose works are read worldwide, it seems to me that Galeano has come to feel the execution of his arguments, the act of turning his passions and anger into ink, was flawed due to a lack of specific education. Furthermore, there exist very few arguments and beliefs to which there are no somewhat justifiable retorts or reservations, and Galeano is aware of this. In an interview in 2001, he noted that even his own “certitudes have doubts for breakfast.” For me, this is the realistic realisation that there are other points of view that oppose his arguments – Galeano is not saying his are supreme nor that they will remain timelessly certain. Reality does indeed change. Structures crumble; institutions morph and sprout other arms and divisions; lands are sown with new seeds and sweat; certainties

evolve uncertain (the world is flat); before unfelt or unseen considerations emerge important from the shaking and speeding-by history. Nonetheless, the structures and “voices of power” that Galeano was writing about in the early 70s still survive today, and he still seemingly opposes their existence, although – as is often true of Galeano – his optimism shines through, this time apparent when in an interview from August last year, he anticipated a change: “From day to day, hope is incubated, little by little, and in a while will rise up and teach us to fly in the dark, like bats.”

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.