In the Footsteps of Orellana and Carvajal

03 December, 2013When Gaspar de Carvajal, the Dominican friar, chronicled the voyage of Francisco de Orellana (1541-1542) down the Rio Napo and into the Marañon and thence to the Amazon in Relación*, his account was lodged in the Archivo de Indias and largely forgotten for 353 years.

Indeed, it wasn’t until 1895 with publication of The Discovery of the Amazon, subtitled “According to the Account of Friar Gaspar de Carvajal and Other Documents” by Chilean historian, José Toribio Medina, that much was known about this expedition. Later it was republished by the American Geographical Society in 1934 and is now available as a Kessinger Legacy Reprint.

Medina’s study was the first serious analysis of Orellana’s role (with supporting texts) in Gonzalo Pizarro’s expedition to La Canela – the Land of Cinnamon – in February 1541 and what happened thereafter.

*[Full Title: Relación del Nuevo Descubrimiento del Famoso Río Grande que Descubrió por Muy Gran Ventura el Capitán Francisco de Orellana/Account of the Recent Discovery of the Famous Grand River which was Discovered by Great Good Fortune by Captain Francisco de Orellana.]

Putting the Record Straight

The historical record, hitherto, had relied heavily on exerpts that appeared in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo’s Historia General y Natural de las Indias (General and Natural History of the Indies, written in 1542 but not published until 1855). In it, Orellana was accused of abandoning Pizarro’s hunger-wracked party to their fate, when he set off with 50 men (and Pizarro’s consent) to try and procure supplies downriver. It was February, 1542. He didn’t return. Oviedo’s reading of events, however, clashes with the affidavits given by those who accompanied Orellana and, by the man himself, in a statement to the Emperor Carlos V (Carlos I of Spain).

Having travelled 200 leagues (a league equates to 2.6 miles) down fast-flowing rivers through inhospitable country where food was scarce, in the end his party hadn’t the food, the capacity, the support or the means to alleviate Pizarro’s predicament. There was no way back. They were both in the same famished predicament only in different places.

Tantalus

Private empire-building was not unusual among the conquistadores. Indeed, the battle between the Almagros and Pizarros for control of Quito and Peru (Nueva Castilla) is a case in point. But as Carvajal’s testimony attests, Orellana, was put in an impossible position from which, like Pizarro, he was fortunate to escape.

Whilst dreams of El Dorado primed the imagination of everyone from Diego de Ordaz (1480-1532) to Francisco de Coronado (1510-1554) to Hernando de Soto (1496/1497–1542), for the most part the accounts from Indians about the existence of El Dorado often turned out to be tantalising promissory notes.

Sold on Going Down the River

Gonzalo Pizarro (1502-1548), Francisco de Orellana (1511-1546) and Lope de Aguirre (1510 -1561), three conquistadores who entered the Amazon jungle’s clutches in the first half of the 16th century, escaped by the skin of their teeth. Others weren’t so lucky.

Indeed, at the conclusion of Colombian writer José Eustasio Rivera’s novel about the rubber boom of the 1920s, La Voragine (The Vortex, 1924), the narrator says of the hero (Arturo Cova) and his compadres: “The jungle swallowed them up.” For many adventurers the jungle has been seen as a monstrous natural autarchy that consumed all who fell within its grasp.

Emerald Heaven or Emerald Hell?

Werner Herzog, who directed Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes (Aguirre: Wrath of God, 1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982), talks of an “emerald hell”.

Europeans didn’t fair well in this milieu nor, as subsequent events and epidemics would prove, did the indigenos who came in contact with the Spanish and Portuguese. For the Europeans, it was another “dark continent”, where if disease didn’t get you, hunger, insects, wild beasts, hostile Indians or madness would. The world knew it as a place of seeming abundance, which paradoxically couldn’t, so it was thought, support more than isolated bands of hunter-gatherers.

Small World

Carvajal’s tale appeared fantastic. His claims of extensive human habitation and societies organised on more than a village level seemed fanciful. Some, like American archaeologist Betty Meggers (1921-2012), didn’t believe that the nutrient poor, acidic oxisols (soils) could support more than the minimum recycling of nutrients required to sustain an unchanging fetid equilibrium. In Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise, published in 1971, she was unequivocal: there just wasn’t enough resources to sustain agriculture, significant population densities or social organisation beyond that of the “pop-up” hunter-gatherer village.

From A to Z

The Amazon has always been a good place to disappear. Colonel Percy Fawcett, an eccentric British adventurer and surveyor, vanished in 1925 in search of the Lost City of Z, a latter-day El Dorado thought to be somewhere on the Upper Xingu in Mato Grosso. The jungle lived up to its reputation. Fawcett is thought to have misread Manuscript 512, housed at the National Library of Rio De Janeiro by Portuguese explorer (bandeirante) João da Silva Guimarães, who claimed to have visited a ruined city in the sertão (outback or hinterland) of Bahia (not Mato Grosso) in 1753.

In his book The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon (2009), Michael Grann claims that Fawcett was really onto something. The archaeological site of Kuhikugu on the Xingu shows evidence of defensive ditches, pallisades, huge plazas (one of which is 490 feet across), canals and roads. Other evidence that the Amazon basin wasn’t as wild as it is now comes in the form of work by Alceu Ranzi, a Brazilian geographer, who discovered geoglyphs, roads and large-scale encampments, when flying over the deforested areas of Acre, the lowland Brazilian state which abuts the frontier with Peru.

Terra Preta

The presence of terra preta (black earth), nutrient-rich anthropogenic soils (high in nitrogen, phosphorus, calcium, zinc, manganese etc.) on the Amazon and some of its major tributaries, has come as something of a surprise and has led to a re-appraisal of Carvajal’s account. Perhaps the large-scale tribal confederations and settlements that stretched hundreds of leagues weren’t merely a figment of a fertile imagination after all. What is evident from the distribution of these soils, is how well it matches those places described by Carvajal, namely the territories of the Aparia, Machiparo, Omagua, Picotas and Amazons. As for most of the rest of the Amazon basin, Megger’s view still holds.

The Land of Aparia

Carvajal describes encountering four pale-skinned Indians with fine hair to their waists, who stood “a span taller than the tallest Christian”. They spoke of wealthy cities in the hinterland, but acccording to Carvajal bade their leave never to return. The areas they referred to were part of a confederation which included Aparia the Lesser and Aparia the Great, part of which extended 80 leagues from the Rio Caracuray to the Rio Javari. Carvajal noted that the settlements were so close to each other they were separated by “less than a crossbow shot”. Similarly, the Machiparo territory, a neighbouring confederation, extended 190 leagues (from Rio Juruá to the Rio Japurá/Caquetá).

Cultural Sophistication

According to Carvajal, Omagua territory extended 80 leagues and had 50,000 men between 30-70 years of age under arms; younger men were exempt from military service. In a testament to the level of cultural development, he claimed that Omagua pottery “was superior to that of Malaga”, where the finest Spanish ceramics originated. The territory was described as having roads (“royal highways”) into the interior. One settlement was five leagues long and in a tribute paying relationship with an overlord, Ica, who was rich in gold and silver.

Land of Plenty

On the boundary between the Machiparo and Omagua confederations, there were redoubts on bluffs ruled over by Omaguci/Oníguayal. Paguana, a land of villages two leagues long, was described as having many sheep (llamas) like Peru, was rich in silver, pineapples, avocados, plums, chirimoya and roads, and lay at a point where the river was so wide they [the Spaniards] couldn’t see the opposite bank.

At the point where Omagua territory ended, the people were described as “stocky”, bore wooden shields and lived in stockades “fortified with walls of heavy timber”. Inside these “gated” fortresses, were large plazas in which carved wooden reliefs 10′ across stood in pride of place supported on “carved lions” (most probably jaguars).

Heads and Tales

Carvajal then describes the Provincia de Picotas (the Province of Gibbets – named because of the number of severed heads of vanquished warriors decorating its portals ) as extending 70 leagues downstream from Omagua lands.

After the land of the Picotas, Orellana came upon two white women and “many Christians” with Indian wives. It is intimated from the Archivo de Indias that perhaps these people were the survivors of the ill-fated Diego de Ordaz (1480-1532) expedition which in its search for El Dorado skirted the Amazon delta before heading up the coast to safety. One of the ships, under the command of Lt. General Juan Cornejo (1531), was wrecked just north of the Amazon and the entire party “lost to the jungle”.

Stranger Than Fiction

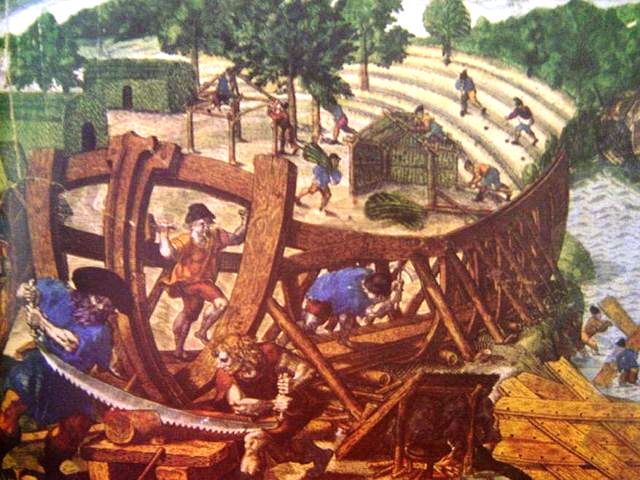

From the largely pacific and compliant lands of the chief, Aparia, on the upper tributaries of the Amazon, Orellana, thereafter, ran the gauntlet of fast currents and tribes so hostile it was difficult for the ships to put into shore. At one point the brigantine (which they’d built en route) had so many arrows embeded in its timbers it “resembled a porcupine”. Yet, nevertheless, Carvajal continued to remark on encountering thousands of Indians, hundreds of canoes, villages of “glimmering white” and areas that were so thickly settled they took “two days and two nights” to pass. Given that shore visits were sporadic, for the reasons described, the implication of this is that such things were commonplace and clearly visible from midstream.

Of Overlords and Amazons

Carvajal describes “13 overlords”, chiefdoms and tribes which went by the name of Irimara, Irrinorrany, Amurians, Conuipuyara and a further “26 overlords”. None of this concurs with the idea that the Amazon littoral was an almost primordial wilderness. Indeed, the mere mention of words like “overlords” and “tribute” is suggestive of a much more complex political and social order.

When it comes to the eponymous Amazons and beyond, Carvajal said: “There are very large cities that glistened white and besides this land is as good, as fertile, and as normal in appearance as our Spain…” Of the Amazons themselves, Carvajal noted their bravery and described their mores and customs through the aegis of an indigeno press-ganged into service as a guide. Was Carvajal accurate in this or was he bigging it up for the delectation of others? There is little doubt that “very large cities” is a relative term but then Carvajal was at least familiar with places like Sevilla and the Royal Capital, Valladolid, for reference.

Approaching the Delta

The Provincia de San Juan, which extended 150 leagues, was ruled over by the overlord, Couyuco/Quenyuc. This same region was said to be densely populated (according to Indian guides) and had roads and stone houses with doors. In these tidal reaches, dominated by Carib tribes, the chief Arripuna was “the overlord of white men and Christians”. Further on there is mention of Tinamostón, chief of La Provincia de los Negros (actually tribesmen covered in black body paint) and the chiefdom of Nurandaluguaburabara-Ichipayo, which resided in fortresses built on hills stripped of vegetation.

Fables and Facts

Unless Carvajal was a congenital liar, a fantasist, a madman, given to exaggeration, or perhaps all four, there is every likelihood that any future infra-red satellite surveys of the Amazon littoral and its principal tributaries (especially where they join the Amazon) will show up what history has alluded to, what the jungle has concealed and what archaeology and social anthropology have so far missed. It may not reveal El Dorado but it will certainly improve our understanding of the level of development of pre-Columbian culture in this region.

Whilst Carvajal’s account lacks the observational flair and drama of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (1488/1490 -1557/1558) Naufragios, published in 1542 (which recounts his peregrinations round the Gulf of Mexico from Florida to Culiacán, Sinaloa after the Narváez expedition was shipwrecked), or Bernal Diaz’s Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España (The True History of the Conquest of New Spain), it does suggest that the Amazon littoral wasn’t how we perceive it today.

The Discovery of the Amazon: According to the Account of Friar Gaspar de Carvajal and Other Documents by José Toribio Medina and Bertram T. Lee, edited by H. C. Heaton (Professor of Romance Languages, New York University), was published by the American Geographical Society (1934) and is republished by Kessinger Legacy Reprints.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.