‘Copa 71’ Uncovers The Buried History Of The First-Ever Women’s World Cup

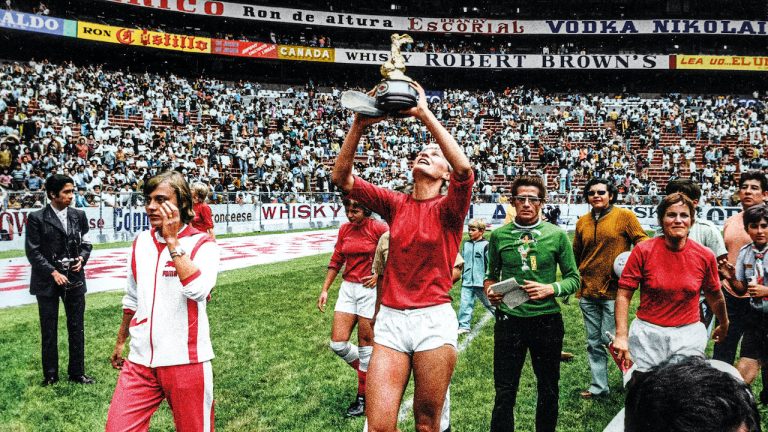

14 October, 2023According to FIFA, the highest attendance for a women’s football match is 91,648, recorded at Barcelona’s Camp Nou in April of 2022. That figure, as large as it is, pales in comparison with the unofficial number of around 110,000 spectators who crammed into Mexico City’s Azteca on the 5thof September 1971, for the final of what is now regarded as the first-ever Women’s World Cup. Despite the stunning scale of the event, however, the 1971 Campeonato de Fútbol Femenil has largely been forgotten, an historical oversight which Rachel Ramsay and James Erskine’s Copa 71 (UK,2023) aims to address over 90 minutes of captivating action.

The most arresting part of this film is the sheer scale and vibrancy of a forgotten spectacle. The immense stadia, rapturous crowds, armies of journalists and stunning footage – an endless feast of lush greens and pin-sharp crowd detail –make it genuinely baffling that these images have remained buried for over fifty years. Indeed, the incredulous response of Brandi Chastain – one of the most decorated female footballers of all time and someone as deeply immersed in the women’s game as it is possible to be – serves as a fitting tagline when she is shown clips of the tournament in the film’s opening scene: “Why didn’t I know about this?”. Chastain’s question is partly answered by the masterful David Goldblatt, who is on hand to describe the obstacles which have long been arrayed against female footballers. After some stunning early progress for the women’s game, the sport’s male establishment brutally retaliated, with the English FA banning any affiliated club from allowing women to play on their grounds. The FA ban, which was quickly copied across the world, effectively forced women’s football into obscurity, though girls of course continued to be enchanted by the game. Indeed, one of the film’s most edifying features is its depiction of the universal passions which football inspires. There is a strange correspondence, for instance, between England’s Carol Wilson, who first sparks at the roar of St. James’ Park in Newcastle, and Silvia Zaragoza, who “felt my freedom for the first time” with a ball at her feet on the streets of Mexico City.

These young women, alongside their counterparts from Denmark, Italy, France, and Argentina, found an unprecedented stage in Mexico in 1971, a first-of-its-kind rogue tournament which the film anchors well in the broader political context of the 1960s and 1970s. As the international movement for women’s liberation made gains in social, political, and economic spheres, football too became an arena for feminist progress, with Zaragoza’s teammate Elvira Aracén describing her own involvement in the tournament as “a political act”. FIFA, inevitably, was quick to impede any progress, and imposed a blanket ban on involvement from any affiliated football association. The organisation’s “negative, violent and aggressive” reaction, in the words of Goldblatt, is a constant leitmotif throughout the film, and very nearly snuffed out the tournament before it even started. Alongside this institutional conservatism came a wave of mockery for female footballers. In one early scene, a maddeningly twee journalist asks England’s Trudy McCaffery “what’s a nice girl like you doing playing football?”, while one French news report describes women’s football as “an erotic or comedic curiosity”. Against this ridicule and disrespect, there is a sense of shared mission between the competitors in Mexico. In one heartening scene, for example, when the Danish team bus breaks down on the way to their match against Italy, the Italian squad comes back to give them a lift to the stadium.

This solidarity did not mean the tournament lacked bite.Italy’s match against Mexico devolves rapidly into shocking violence, eventually having to be abandoned 10 minutes ahead of time with players from both teams sprawled on the turf. Later, before the final between Denmark and the hosts – which the former won by three goals to nil –, the Danish squad are forced to stay with compatriots across Mexico City to get some rest, so boisterous are the crowds gathered outside their hotel. The Danish players do not seem upset by this disturbance, however, interpreting it rather as proof of just how much the tournament was taken to heart by the Mexican public. This is by far the most inspiring element of the film, with one player remarking with surprise that not only women and children, but “grown men” filled the stadiums. Clearly, the film argues, the appetite for women’s football had always been present, with only a little bit of encouragement needed to create the spectacle we see in Copa 71. That is not to say that the attention was always positive, of course. Indeed, some of the coverage hits very awkwardly, with one Mexican journalist noting that a key part of media strategy was stressing that the players were not “muscular monstrosities” but “generally pretty girls”, and one organiser even suggesting that the uniforms be as close as possible to hot pants. Despite these drawbacks, however, the 1971 World Cup represents an enormous milestone in the women’s game, whose immense progress was proven – as if it needed further proof – by the success of the recent Women’s World Cup in Australia and New Zealand. Quite rightly, Copa 71 presents its own subject as a foundation for such achievements, and it is half-tragedy, half-outrage that the tournament has gone unheralded until now.

Copa 71 is showing as part of the 67th BFI London Film Festival running 4-15 October and will be released in the UK in 2024.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.