Have You Heard Of Beiradão? Know The Story Behind The Amazon’s Most Popular Sound

25 February, 2022More than 7 million, this is the number of views accumulated by the Portal do Beiradão channel on YouTube. Led by the musician, singer and composer Hadail Mesquita, the channel has been on the air since 2016 and has been gaining popularity in Amazonas by promoting a new Amazonian music scene announced in its name: Beiradão.

For Hadail, the idea of making the channel was born out of necessity. In an interview with Portal Embrazado, he said that he had not found space to publicize his work and realized that other musicians in the region also had the same difficulty.

“A singer who lives all the way there in the interior of Amazonas will never have a shot on a radio show here in Manaus. There will never be a TV appearance, you understand? So there had to be someone to take their work and somehow advertise it. There had to be a channel to tell the story of some musicians who were forgotten, who were dying and taking the story with them”

Hadail, who despite living in Manaus, is from Largo do Limão, a town in the municipality of Iranduba.

Today, with over 36 thousand subscribers, Portal do Beiradão follows the trend of channels such as Kondzilla (São Paulo), Tops da Arrochadeira (Bahia) and Thiago Gravações (Pernambuco), which also work as music distribution labels and trendsetters, leveraging peripheral scenes by centralizing releases on their YouTube channels, concentrating artists who identify with their respective market niches and who previously did not find spaces for production and dissemination in traditional media.

In this way, Hadail managed to give visibility to the musicians and above all he raised his own name. His music video for “Com Caboquinho é Assim” is perhaps the biggest indication of this turning point in his career. The song exploded in Amazonas and neighbouring states, gained versions in different musical genres and has helped boost Hadail’s name, who until the arrival of the pandemic had a very busy concert schedule.

The lyrics evoke folkloric elements from the Amazon, such as the caboco fish-eater, a forest environment and the tides on river navigations. The highlight, however, appears in the cosmopolitan reprocessing of the boto encantado myth [the boto encantado is a creature that is dolphin by day and lady-seducing man at night], adept of relationships without compromise. Although the song sounds like an electronic forró or lambadão in the cuiabano style, what draws attention is precisely the beiradão, which appears not only in the title of the channel, but also as a genre of music.

Before The Beiradão, The Beiradões

The first documented reference to the beiradão dates back to 1958, when journalist and politician from Amazonas, Álvaro Maia, launched a novel of the same name. At the time, Álvaro used the term to speak of the banks of white water rivers, populated by the first explorers of those lands and their descendants. “There, big chestnuts and rubber trees were found, without the wealth and abundance of the tributaries of black waters, as well as towns and municipal headquarters”, defined the author.

62 years after the publication of the book, this notion of beiradão has gained new interpretations. In an interview with the webseries A Poética dos Beiradões, musician and art-educator Eliberto Barroncas points out the role of broadcasters in the capital of Amazonas to shape new meanings: “They said: ‘there will be a party at the beiradão X, at the edge of the Costa do Catalão, there in Cumã, Paraná do Autaz Mirim… There at the ‘beiradão’… ”. Thus, in a period when the radio was one of the main vehicles of communication among the inhabitants of Amazonas, the manauaras [people of Manaus] began to create another cultural notion of the beiradões, which now included the festivities and music played in these places.

Already at that time, the festivities were usually associated with religious events, football championships and/or the harvest season, such as the Festa do Guaraná in Maués. The boats, decorated for the event, started the festivities while still on the long trips crossing the rivers of the Amazon, with shows and much dancing before they even landed on the beiradões. At the climax of the festivities, the interest was turned to music and dances in the terreiros, which are open spaces in the field; or at the headquarters, which are small places, built with wood, for community meetings and social actions, or parties with musical attractions.

Xotes, baiões, lambadas, cumbias, sambas, frevos, chorinhos, and boleros were musical genres that composed the repertoires of these festivities and also the daily lives of the residents.

Despite becoming better known among the manauaras with radio broadcasts, these festive traditions in the beiradões date from a period when this media did not even exist. Eliberto draws attention to this in an interview published in the researcher Rafael Norberto’s master’s dissertation:

“Beiradão music has been around since rubber exploration times, when the north-easterners came here. At that time there was no radio, so they played music, had their own parties, danced man to man in the rubber fields, due to the absence of a social life with women. They danced with women, but they also danced with men”.

Eliberto Barroncas

Instruments and Regions

Ethnomusicologist Daniele Colares Lins, in her master’s thesis published in 2018, reinforces this argument by Eliberto. By invoking elements of the personal trajectory of Seu Rosário, a violinist residing in the city of Parintins, the researcher gathers important information to enable a reconstruction of the history of the festivities of the beiradões of the lower Amazon region. She points out the existence of these celebrations at least since the middle of the rubber cycle, at the beginning of the 20th century.

The influence of north-eastern migration on the sounds of these festivities is also reinforced by Daniele, when the author points out the presence of rabecas made by north-eastern workers and also by the indigenous people of this same region, both seeking to build a violin from the materials accessible there.

If in the Parintins region the rabeca (a kind of violin) and / or the violin assumed a certain role in the sounds, on the opposite side of the state, in the border regions with Acre and Colombia, the accordion was a more popular instrument and the north-eastern forró was the most present rhythm.

Researcher Rafael Norberto, through an interview given by Zoom, was the one who contextualized us stating that, despite identifying these signs, he recognizes that these regions of the state still lack more dense studies in the area of ethnomusicology. However, for the researcher these characteristics denote how the protagonism of certain soloist instruments is related to the geographical dimensions.

Accompanying the violin, rabeca and accordion, there are also instruments such as banjos, drums, tambourines, comb flutes, espanta-cão and xeque-xeques. However, considering all regions of Amazonas, it seems that the sax has become the most relevant instrument.

The phenomenon is visible in the number of saxophonists who stood out in Amazonas from the beginning of the 20th century and also in the remarkable resilience of a sound that is still widely sampled.

This is due to an important factor — the military bands of Amazonas were essential in the popularization of the musical instrument among the riverside inhabitants. In many beiradões, the musicians of these bands were the only readers of musical notation in contact with the riverside people, whose learning was often at parties, in contact with other musicians, and/or listening to the radio. Rafí do Sax, a deceased police officer and member of the Military Police Band Ensemble, is a recurring name of reference among older saxophonists, as revealed by Rafael Norberto’s research.

Let My Sax In

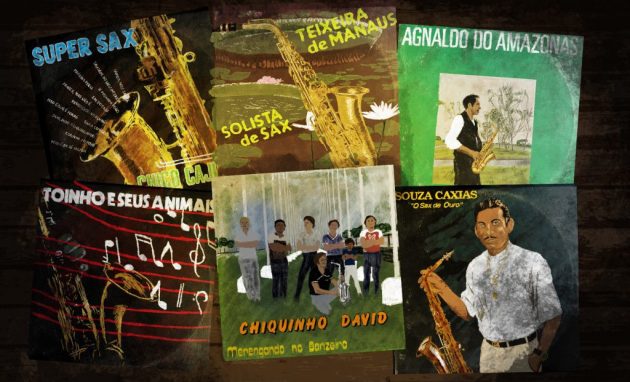

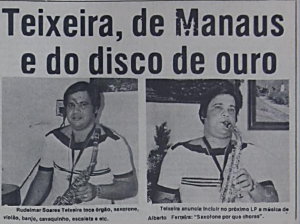

The year is 1981, the most successful album in Amazonas is Solista de Sax, the debut of Teixeira de Manaus. The album was recorded in five days at the Copacabana Discos studio, in São Bernardo do Campo, São Paulo. Rudeimar Soares Teixeira would never have imagined that he would change the history of music in Amazonas once and for all.

Darle Silva Teixeira, daughter of the musician and researcher responsible for a dissertation on his father’s work, reveals that when he was invited by Pinduca to record the album, Teixeira doubted the proposal, thinking it was a joke.

In an interview with Jornal A Crítica, in January 1983, Teixeira de Manaus commented on the episode. “Pinduca insisted a lot. And I thought there was only going to be a feature on his album”, he said.

The penny dropped only when the musician saw the avenues Eduardo Ribeiro and Sete de Setembro, in the centre of Manaus, crowded for the event in which he would receive his first golden record (equivalent to 100 thousand copies sold) with a live transmission by Rádio Difusora.

From The Brothel to National Success

More than a sales success, Teixeira de Manaus became the precursor of the phenomenon that gave record labels an Amazonian accent in the way of performing popular rhythms of that time. In this first record we can hear samba, merengue, lambada, carimbó and forró, all played in a very particular way and with striking peculiarities: short lyrics of two or three sentences, sung only in the choruses, contrasting with the long solos and the always present harmonic instrumental, made for dancing.

Although residing in the capital of Amazonas and discovered by Pinduca while performing at a brothel in the city of Manaus, Teixeira fulfilled most of his schedule of shows on the edges of the Amazon. And in the wake of the success of the first album, musicians such as Chico Cajú, Chiquinho David, Agnaldo do Amazonas, Souza Caxias, Toinho e Seus Animais and many others who were already popular names in the interior of the state emerged, but only after the explosion of Teixeira they had access to the record label circuit.

In this way, Teixeira — who is not from Manaus but a native of the Costa do Catalão community, in the municipality of Careiro da Várzea, two hours away from Manaus — involuntarily started to boost Amazonian music after achieving national success.

The Guitar Boom

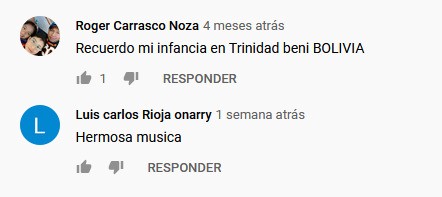

Along with the success of the saxophonists, in that same decade of the 80s other instrumentalists gained space in the songs of the beiradões. Nonato do Cavaquinho was one of them. His biggest hit, “Cumbia Exportação”, animated parties not only in Brazil, but in Bolivia it also marked a time for some people, as shown by some of the comments on its publication on YouTube.

Although the cavaquinho had its presence, the insertion of the guitar was definitely of greater impact. The albums of Oseas e Sua Guitarra Maravilhosa, André Amazonas and Magalhães da Guitarra were nationally successful and are seminal in the history of Brazilian guitar.

Of these, Oseas was the first Amazonian guitarist to record a solo album and his introduction in the phonographic market was also by invitation of Pinduca, who told us how he discovered the musician from the city of Tefé.

“On a given Sunday when I — even partying a little, Sunday morning — had nothing to do, I went for a walk and someone said ‘There is a place they call Casa dos Artistas. Let’s see what’s going on there.’ I got there and saw that little boy playing the guitar, but playing at a very good speed! I was pleased”

Pinduca

Before recording his own album, Oseas recorded for the group Lambaly (in 1981) and also for the collection Guitarradas (1983), by Gravasom, under the pseudonym of Carlos Marajó — the same name that would later be assumed by the paraense guitarist Aldo Sena [this name, Carlos Marajó, was created by the Carlos Santos, owner of Gravasom]. On his first solo album, Oseas stood out. In an interview with the webseries A Poética do Beiradão, the musician tells that he even got a golden record and performed at the TV show Bolinha Show, which was a huge hit at the time.

For researcher Rafael Norberto, when compared to the sax, for example, the guitar was not so popular in the beiradões. He claims that the riverside people had already been playing with the instrument before the first records, but the consecration came later.

“It was not the most popular instrument among riverside folks, among the inhabitants of the interior. The guitar arrives and will actually become popular with the phenomenon of recordings, around the 80’. Right after André, Oseas, Magalhães started playing… Then there was a guitar boom in the countryside.”

Norberto

Oseas stood out among all, not only for being the precursor, but above all for having invented a unique language that characterized the Amazonian guitar, celebrating lambadas, forrós and sambas with frantic solos in dance music. André Amazonas and Magalhães, who recorded soon after, had a language closer to choro and frevo, for example.

However, they had in common a way of playing that was similar to the sound of the saxophone. “In general, if you are going to analyse the musical issue strictly, you will see intervals that are normally used on the saxophone”, points out Rafael.

Stay tuned for a second article in this series which will look at how the movement became invisible around the 1990s and speak about the return of beiradão as a musical genre from 2012.

This article was originally published by Portal Embrazado, an essential portal for discussing marginal music in Brazil.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.