The Time and Being of Gilvan Samico

26 November, 201325th November, 2013 was a strange day. It was the day Sounds and Colours released our new book/CD Sounds and Colours Brazil. It was also the day that the incredible Brazilian artist Gilvan Samico passed away. The following article about Samico was originally written in Portuguese by Arthur Dantas and was published in the Brazilian magazine Soma+ in 2009 (you can read the Portuguese version here). We are huge fans of Samico’s work and wanted to make him one of the featured artists in our upcoming Brazil book so translated Arthur’s article into English especially for the book [The translation was done by Julia Duarte]. The fact that he passed away on the same day the book was launched has left a bitter-sweet taste in our mouths. Salve Samico! You were one of the best! – Russ

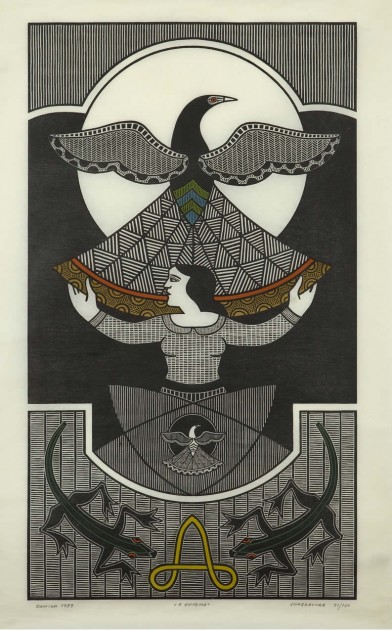

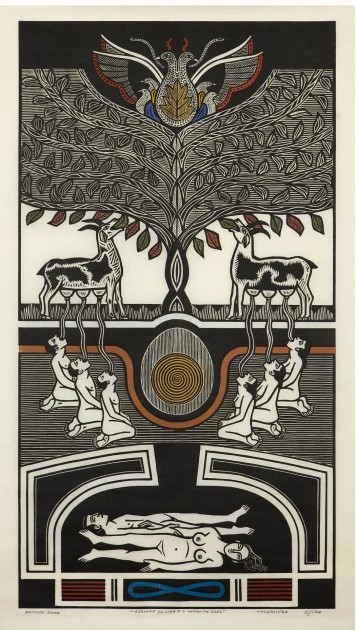

“Time runs slow for the artist. Engraving takes patience and craft. Samico is not virtuous, ‘I am not skilled’, he often says. Instead, he works empirically, on the basis of error and accuracy. But when the work is completed, we are certain that it will be flawless, a work of art of breathtaking beauty. Samico balances, in defined doses, imagination and detachment, fantasy and technique.” – Frederico Morais, in Gilvan Samico: Works from 1980 to 1994.

It is said that the Pernambucan artist Gilvan Samico (pictured above left, with Derlon Almeida), 85, does not like talking. Like his art, his conversation is direct and frank. From his home-studio in Olinda, just steps away from the Monastery of St. Benedict and overlooking the city of Recife, he talks to me by phone.

Samico attributes luck to all the artistic achievements of a career in which destiny really has been a faithful and generous partner. “Back in Afogados [a neighbourhood of Recife], I used to live with my aunt and her two children. One day, I found a notebook in her house with a woman’s head, a movie star, which she had drawn. I looked and thought: how could someone copy it so well that I recognized it was a movie star?”

The young Samico had discovered a whole new world that would unfold before him. His family, without any intellectual or artistic pretension (“there wasn´t even a book at home”), begrudgingly began to encourage the talents of their child. One day his father took him to the house of the artist Hélio Feijó, who looked at his early drawings, still reproducing what was in the magazines and said: “Instead of copying magazine covers, copy what you see, what’s in front of you!” It was then that Samico started drawing trees and animals like goats, birds, snakes, frogs. This was an artist primarily interested in his own land.

The artist and former art dealer Giuseppe Baccaro says that the process of engraving is difficult, almost ascetic. Engravers are often elusive types, with no special effects in life or in art. It’s a theory that’s seen in Brazilian artists of the genre like Goeldi, Abramo, Gruber, Roberto Magalhães and Gilvan Samico, to name a few.

Samico is not just “anyone” in Brazilian art: he has works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and has participated in two Venice biennials, where he has won awards. But these are nothing new in a career in which Samico started as a painter before moving into engraving. He made the first of these in 1953. “It was not my choice. Abelardo da Hora thought it was easy to make an outline of wood and plaster on top of glass. When dried, it was polished already. But the plaster is brittle, a horrible material to engrave with. At home, I made a couple of pieces using wood engravings and this was my experience until I moved to São Paulo.”

The Masters, Goeldi and Lívio Abramo

In 1957 Samico decided to try his luck in São Paulo. “There was a lot more going on there, there were museums of art, it was a big city, with many more attractions for artists.” With recommendations from experienced artist friends like Aloísio Magalhães and Francisco Brennand, he decided to study with Livio Abramo in São Paulo, who would, in turn, recommend that Samico study under Oswaldo Goeldi in Rio de Janeiro. This first phase of Samico’s work is consistent with the great work of Abramo and Goeldi, featuring expressionist engravings in which the cut would often simulate lines of a pencil drawing, evident in the piece Três Mulheres e a Lua (1959).

Samico was very shy and learned more from listening than producing in his classes. He rarely showed any of his engravings to his teachers, focusing instead on what they said, how they judged his fellow students’ work. Once, Lívio Abramo was intrigued as to why Samico always worked in the shadows, in the corners. “When I was in front of an easel and someone walked behind me, I would stop”, said Samico.

The most curious thing, however, was a physical limitation that caused Samico to ultimately opt for engraving. As his city apartment was very small and there was a newborn daughter, the artist had to opt for the less space-intrusive choice of engraving. It was a moment of destiny for the artist, who would work on his engravings in his spare time, following a strict daily routine. Soon his work began to be noticed by art galleries.

Like a Cordel Tale

In 1965, after seven years away from Pernambuco, the good son returned to his homeland, though exchanging his hometown of Recife for the nearby Olinda, where he still lives today. Olinda would not be the only change in the artist’s life: a conversation with the writer and defender of popular northeastern culture, Ariano Suassuna, would change his life. “I was not satisfied with the engravings I was making. They were very dark and had no indication that I was an artist from Brazil. I said that to Ariano [and] he told me: ‘Samico, why don’t you take a dip into the world of cordel?’ That was like a kick from a mule to me.”

Samico started researching the covers of the traditional northeastern cordels. He studied them carefully and came to a logical conclusion: more than the pictures themselves, the solution was to concentrate on the texts, to confer graphically the most recurrent images of the cordelista [the writer of the cordel stories]. In the 60s magazine Senhor, Samico would clearly define the change of direction in his work: “I stripped excesses from my engravings. The concern to enrich them with different textures was replaced by the concern to enrich them with invention”. Thus, instead of creating a language similar to the popular engravers, he found his own, unique and original path.

It was a time of vain nationalist intellectuals, of artistic movements and manifestos, of mobilization in favour of Brazilian popular culture, continuing the policies of the Vargas era that had swung in that direction. In Pernambuco, Suassuna started working with artists around these principles, leading to the birth of the Armorial Movement, which in turn revalued northeastern popular culture, creating a studied Brazilian art from popular roots. Besides Suassuna, other artists and organizations such as Francisco Brennand, Raimundo Carrero, the Northeast Armorial Ballet, the Armorial Chamber Orchestra, the Orchestra Romançal and Quinteto Armorial were involved in the movement. Samico, who found his own artistic ideas perfectly in line with the ambitions of the group also participated. He explains, however, that it was an armorial avant la lettre. “I don’t conform to the ideas of the Armorial Movement: I was already armorial without even knowing it!”

Far From Reason

His work since then has become more “Brazilian”. Instead of spying on the European expressionism happening on the other side of the ocean, Samico returned to the figurativism of popular engravers and looked to purify his work through economy of strokes, perspectives and colours. He turned his engraving inside out, revealing light where there was darkness, deepening the volume of the images and creating definitive black lines. He abandoned any pretension towards perspective, removed excesses and went to work with designs that included a maximum of three characters or subjects.

The procedure transformed everything and brought to light his unique plan, with no sense of depth or perspective and keeping just the minimum of details. “I reduced the engraving to a figure in linear form, some black areas, and a slight stroke to animate. It had no hint of sky, cloud, anything resembling a naturalistic space.”

With his exposure at MoMA in New York) and at two Venice biennials, as well a plethora of group and solo exhibitions around the world, Samico claims that his only frustration is not being recognized as a painter. “It’s a little thing that happens with some artists that, using more than one technique, are the most recognized in one, at the expense of others. I would like to have the prestige I have, not only as an engraver but also as a painter. I may not be able to show my paintings, but I put colour in my engravings.”

Gilvan’s work has an extreme accuracy. The exhibition Samico – Drawing the Engraving, which took place between August and September 2004 in the state Pinacoteca, is proof of the absolute zeal with which he treats his creations; there are some works in his catalogue which come accompanied by reproductions of the many stages of ‘study’ for the final piece. It’s a somewhat disturbing process. Now in his 80s, Samico says, not without a dose of his quirky humour, that he prefers to work less, “I can´t change my ways [even though] engraving tortures me.” Thus, for more than ten years Samico has produced only one work per year, limiting pressings to 120 copies for his fans and collectors.

A few days after the interview, my appreciation for Samico and his work increases, I think about going to Olinda to give him a hug and thank him for a life devoted to recreating the world as we know it. I call to solve some small bureaucracies and take the opportunity to thank him once more for the pleasure of sharing a few words with me. I mean I was afraid, because of his reputation as a man of few words. “Yeah, I invented a legend that I was walking down the street distracted and hit my head on a post and since then I can´t stop speaking,” laughs Samico. Maybe the post of his personal fiction is the same one that our head hits when confronted with his engravings.

You can see lots more of Samico’s art on this dedicated Facebook Page.

This article was published in Sounds and Colours Brazil, a book and CD focused on Brazilian music and culture. You can find out more about the book at https://soundsandcolours.com/issues/sounds-and-colours-brazil.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.