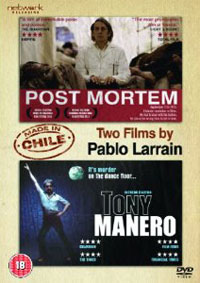

Made in Chile: Two Films by Pablo Larrain

08 February, 2012Pablo Larrain’s latest release, Post Mortem (reviewed separately here) frames a dark and twisted story of obsession and lust in amongst the chaos of the 1973 coup in Santiago, Chile. Morgue worker, Mario Cornejo, ends up being present at the dubious autopsy of Salvador Allende, but not before he manages to indulge a fantasy for a dancer called Nancy. With Haneke-like bleakness and very little mercy, Larrain shows how the bodies pile up and the love story disintegrates even further from its shaky beginnings.

Although also available separately on DVD, a box set Made in Chile: Two Films by Pablo Larrain has now been released which brings his earlier film, Tony Manero back into prominence for a side-by-side viewing merited by overlaps in style and content. Both feature Alfredo Castro playing the main protagonist, are set in 1970s Chile and visit similar themes.

Tony Manero sees Alfredo Castro play the part of a Saturday Night Fever obsessed fifty-something in the run up to him competing in a TV talent show:

“What is your profession?”

“This.”

“What’s this?”

“Show Business.”

But it is clear from an early scene, where Raul beats an old woman to death for very little reason at all, that this is far from an innocent or healthy aspiration.

The juxtaposition of a disco dancing impersonator with the life of a sociopathic murderer is not actually as harsh as it may seem at first. Saturday Night Fever, to those who have seen the full version, is a film about dark twisted and unsettling aspects of urban life, from which disco offers an escape. Tony Manero and his friends get into violent scrapes with local gangs, attempt rape, commit suicide and his older brother even loses his faith as a Catholic priest in a move which crushes his whole family.

Raul’s obsession with this film leads him to see it multiple times, so as to perfectly memorise the dance routine, but he also commits to memory large parts of the dialogue which he recites in English to an impressed crowd, who are unlikely to know what it means.

“One day you look at a crucifix and all you see is a man dying on a cross.”

Raul is a typical anti-hero. As the audience, we are forced to identify with him as we are privy to parts of his personal life which almost make us sympathetic towards him — like watching him dance alone in his room on a homemade under lit dance floor — and we are pulled along by his story from his viewpoint, his troubles are our troubles, which makes it all the more difficult to accept him when he steals, lashes out violently or betrays.

Alfredo Castro, who also has some of the writing credits for Tony Manero, plays his characters in both films with so much social awkwardness and so many creepy mannerisms that they become joys to behold in quite a strange and unsettling way.

Also throughout both films, Larrain uses nudity to similar effect. Sex is always nasty, sleazy and cringeworthy. The naked bodies of the main love interests are totally unappealing: they are the skeletal, grubby and perverse nudes of an undernourished and impoverished society, where desperate attempts to escape the daily misery cannot even be made through sensual gratification. Perhaps this is why Raul must yearn for something which he perceives as being as lofty, artistic and ephemeral as the mystery of the dance to lift him from the mess of his trapped material existence.

Another thing which both films manage brilliantly, like so much Latin American cinema, is to raise political issues without being preachy. The stories are set at different points during the Pinochet regime but choose to focus on the slices of society from the ground upwards, rather than hammer home the political implications of the Generals’ struggles to keep power. Political activism, whether for or against the regime is always something dangerous that other people seem to be doing.

Another thing which both films manage brilliantly, like so much Latin American cinema, is to raise political issues without being preachy. The stories are set at different points during the Pinochet regime but choose to focus on the slices of society from the ground upwards, rather than hammer home the political implications of the Generals’ struggles to keep power. Political activism, whether for or against the regime is always something dangerous that other people seem to be doing.

Admittedly, Castro’s characters are both clearly outsiders due to their inability to interact with other people, and it is somewhat frustrating that no back story or real explanation is given to justify their such extreme traits, but in the tense and stressful life under dictatorship which these films portray, we are shown that all kinds of unpleasant things can happen, normally without justification and usually to those who don’t deserve it.

Made in Chile: Two Films by Pablo Larrain is available to buy now on DVD

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.