No Hay Revolución Sin Canciones: Bolivian Nationalism and its Journey to the World Music Stage

16 February, 2011Known as “the roof top of the world” due to its high elevation in the Andes mountains, Bolivia is a melting pot of indigenous and hybrid forms of music and cultural values. Although sixty percent of the country’s population are Indian, speaking mostly Quechua and Aymara, the traditional music of the country was not accepted as a musical idiom until the 1960s, when it became a key ingredient in the socio-political activism taking place in Bolivia, as well as other countries in Latin America.

Sounding Indigenous

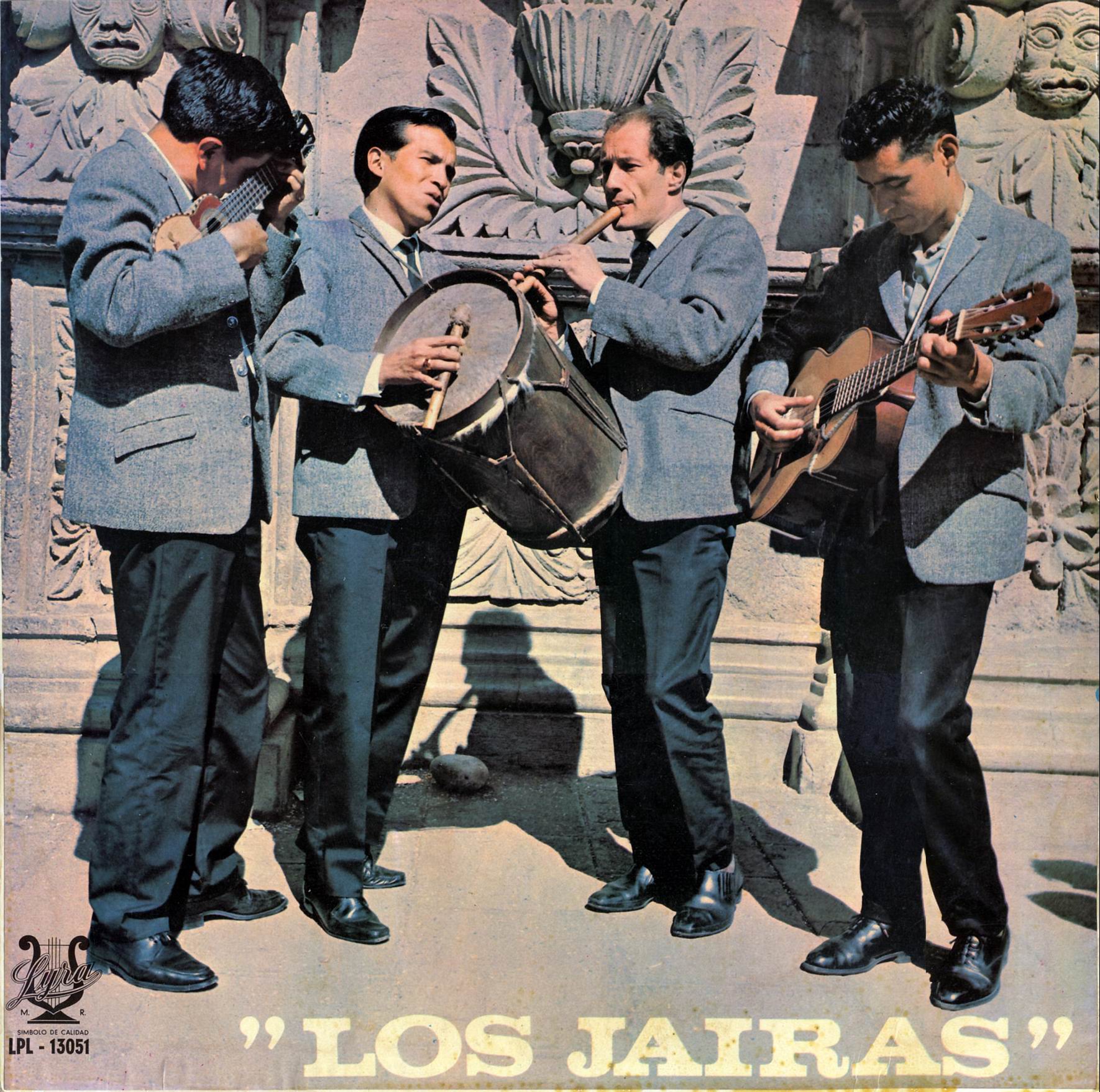

The hypnotic and sumptuous sounds of traditional Bolivian music were introduced and popularized by seminal Andean band Los Jairas. Hailing from the world’s highest capital La Paz (3,600m), the music of Los Jairas was first heard at the Peňa Naira, a traditional meeting place where musicians could voice their songs as well as political tendencies against the cultural colonialism of Latin America by North American and European values. The establishment of Peňa Naira was a result of the social and economic reform that occurred after the nationalist revolution of 1952. The Bolivian government also introduced new laws that favoured the Aymara and Quechua people whilst also initiating agricultural reform and enabling everyone the right to vote.

Previously, most rural communities were tied to a system of exploitation that required free labour in exchange for a minimal plot of land. Bands such as Los Jairas saw in music a means to establish a Bolivian identity as a defence against the upper classes of society who previously had objected to anything associated with the indigenous culture of Bolivia.

Before Los Jairas, the urban popular music was música criolla, a style that was enjoyed by middle and working class people. It was based on a vast repertoire – huaynos, bailecitos, cuecas and the yaravi and performed on instruments such as guitar, mandolin and accordion – instruments that were distinctly set apart from Bolivian indigenous culture. One of the main figures of música criolla was Don Gilberto Rojas, a composer of classics such as “Jenecheru” and “Palmeras”.

During the 1940s and 1950s, estudiantinas, ensembles of around 15-20 players of guitar, charango, mandolin and violin were highly popular amongst the masses. However, instruments such as the charango were frowned upon for its association with indigenous Bolivian culture, especially from the upper classes who deemed it as an instrumento de cholos. Instead, the music of Brazil, the Caribbean, Mexico and Europe were the preferred choice of song of the Bolivian elite due to its aestheticism of exoticness and non-Bolivian values.

Nueva Canción Movement

Musical forums such as the Peňa Naira were not entirely exclusive to Bolivian urbanites. By the mid 1960s, the Nueva Canción movement had spread to most Latin American countries and was intertwined with the revolutionary sentiment of the period. Chilean folklorist and social activist Violeta Parra was a main figure of the Nueva Canción movement whose Andean folk songs were highly political and nationalistic in their lyrical as well as melodic content. Songs such as “Hace Falta un Guerrillero” (It Takes a Guerrilla) and “La Carta” (The Letter) are full of anti-government sentiments, reflecting the solidarity among Latin Americans and their cries of socialist sentiments. Interestingly, the Peňas that were taking place over Latin America were to a certain extent, similar to the Greenwich village scene of New York, where young people were voicing their political opinions through their own folk music revival.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YFL_kWWR-nI

Música Folklórica, Los Jairas and the Transformation of Indigenous Instruments

Back in South America, the Peňa Naira gave way to a hybrid musical form – música folklórica, an urban style that incorporated features of the criollo tradition (Spanish heritage) which transformed elements of indigenous Quechua or Aymara folk music. Indeed, it was Los Jairas with their forging of new rhythmic and melodic style and their re-structuring of traditional Bolivian melodies that paved the way for a musical genre – one that would appeal to an urban, middle-class audience. Founded by Edgar “Yayo” Jofré in 1965, Los Jairas laid the foundations for a musical idiom that would inspire countless bands to come. The original members of Los Jairas included Jofré as singer and percussionist; Julio Godoy as guitarist; Ernesto Cavour as charango player (small ten-stringed guitar) and Swiss-French Gilbert Favre playing the quena (notched-end vertical flute).

Back in South America, the Peňa Naira gave way to a hybrid musical form – música folklórica, an urban style that incorporated features of the criollo tradition (Spanish heritage) which transformed elements of indigenous Quechua or Aymara folk music. Indeed, it was Los Jairas with their forging of new rhythmic and melodic style and their re-structuring of traditional Bolivian melodies that paved the way for a musical genre – one that would appeal to an urban, middle-class audience. Founded by Edgar “Yayo” Jofré in 1965, Los Jairas laid the foundations for a musical idiom that would inspire countless bands to come. The original members of Los Jairas included Jofré as singer and percussionist; Julio Godoy as guitarist; Ernesto Cavour as charango player (small ten-stringed guitar) and Swiss-French Gilbert Favre playing the quena (notched-end vertical flute).

Later they were also joined by renowned guitarist and composer, Alfredo Dominguez who also had a highly successful solo career. From their debut album Grito de Bolivia (1967), Los Jairas gained fame on a national, as well as international scale, winning several prizes and touring with popular figures such as Violeta Parra during her European and South American tour. Songs which gained immense success include “El Llanto de Mi Madre,” “El Llanto del Olvido,” “Alboroza Kolla,” “Memorias” and others popularized abroad such as “El Condor Pasa.”

Los Jairas recognised the potential of traditional instruments such as the charango and quena, transforming them into concert-solo instruments that required real virtuoso technique. Favre, also known as “el gringo” of the band learnt to play the quena in a European style, using vibrato, dynamics and sweeping glissandos – features that had never been dreamt of on a traditional instrument before. Favre’s playing of a Bolivian instrument is also significant in that it heralded the enfranchisement of an indigenous instrument and its peasant connotation vis-a-vis the upper and middle classes, encouraging people to accept Bolivian autochthonous values. In addition, with his highly technical solos and innovative plucking styles, Cavour also opened the flood gates to a newly respected view of the charango, which was now endowed as an instrument of calibre. Cavour even designed a guide to charango, aimed at the middle-class, aficionados- presenting a new tablature for melodies whilst also introducing a various tuning devices.

Thirty-five years ago, Los Jairas marked a milestone in the history of Bolivian music – transporting the music of the Andes to the global stage, reaching the best headphones around the world. In doing so he created a unique pan-Andean sound. Today, the music of Los Jairas presents a significant transition in the history of a post-revolutionary Bolivia that inspired numerous bands such as Los de Canata (1972), Aymara (1973) and Wara (1974). Chilean president Salvador Allende once quoted, “no hay revolución sin canciones” (there is no revolution without song). In regards to Los Jairas, the Peňa Naira and the political revolution it grew out of, his words could not have been more apt.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.