A Creative Island: Rio’s Wunderkind Ana Frango Elétrico Talks Studios, Sex and Saudade

17 March, 2021“I remember just crying!” Ana Fainguelernt, perched on the edge of her bed at her mum’s house in Rio de Janeiro, is recalling the first time she heard her voice on record. “I was listening to it on the car’s CD player, driving back to Santa Teresa with my mum, and I was crying and exclaiming, ‘Mum, I don’t recognise my voice!’ It was uncanny – such a significant experience, bearing in mind, at this time, I didn’t even have a voice recorder on my cell-phone. I never forgot this moment.”

This affecting moment occurred when Fainguelernt was just ten years old – long before she became Ana Frango Elétrico (Ana Electric Chicken), the 23-year-old wunderkind whose 2019 sophomore album Little Electric Chicken Heart garnered plural awards, and, last year, a Grammy nomination.

Back then, Fainguelernt (hereafter, upon her request, Frango) preferred playing football and “kidding around” to studying music. In 2008, she was the shy pupil of guitar virtuoso Aloysio Neves, who had encouraged the ten-year-old Rio native to record a song she’d written in a studio. But, though moved to tears when hearing her voice, this recording session was hardly the spark that set Frango’s extraordinary career in motion. Indeed, despite having already studied at Rio’s esteemed Villa-Lobos music school, the young Frango didn’t get on at all with academic music.

“I remember my mum saying I’ll be thankful once I’m older and, now, I’m thankful to have had the conditions to learn what I did. But at the time, I didn’t like it. I was really shy so it was difficult for me…”

“Back then, I’d never know what chord I was playing. When I was a bit older, I’d research, like, ‘jazz chords’, and just pick one and make a song with it. And I can now see that those chords I learned as a kid, I still use today in different inversions. So it’s cool to look back on. But, back then, I wasn’t like, ‘I’m going to be a songwriter and singer’. I just really didn’t feel that.”

That began to change for Frango at high school when she, alongside her classmates, formed the band Almoço Nu, borrowing the translated title of William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch. “That was my first really happy and exciting experience of music. It was a first experience of music that wasn’t so lonely. With the band, it became something shared, a common interest. And it was really beautiful to create with such fabulous, artistic people – like JOCA [Frango’s friend and nascent R&B talent whose 2019 debut A Salvação É Pelo Risco was received favourably by Brazilian press].

“We were sixteen then. And we had a real feeling of something happening. We made crazy songs – a lot of rock ‘n’ roll and maracatu and a little bit of cumbia and lots of different rhythms… It was at this time I thought, ‘hmm, I’d like to do that.’ I loved the stage. I’m not crazy in daily life but I really loved to play and sing and do crazy things with my voice on stage.

“And then, I started composing stuff that was different to what I was writing with Almoço Nu. This other music had something to do with grunge – I really liked Nirvana, though I’d never listened to much U.S. rock or other grunge… But I was making music, like–”

Picking up an acoustic guitar that had been lying on the bed behind her, Frango plays eight bars of fast blues, leaning on a walking bass. Atop, she sings in her distinctive youthful yelp, the opening lines of Mormaço Queima track “Picles”, leaping easily atop the accompaniment, before stopping as swiftly as she began.

“So anyway,” she continues, with emphatic cadence: “along came Ana Frango Elétrico.”

Taking the nickname ascribed to her grandfather by schoolmates who struggled with his Russian surname, Frango was first introduced as Ana Frango Elétrico when performing at a protest during 2016’s nationwide high-school occupations.

Introduced under this moniker by Eduardo Carvalho – now, a global reporter who was then in charge of the occupation’s sarau (musical programming) – it was a turning point for the creative teenager’s career. Nevertheless, for the daughter of a visual artist, music was always fighting for centre-stage with other arts. And Frango’s burgeoning music career coincided with her enrolling in Fine Art at the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro.

Even though in the last three years, Frango has released her first two albums Mormaço Queima and Little Electric Chicken Heart, and blossomed from awkward and unassuming indie kid to Brazilian music’s poster-child, she has maintained a multidisciplinary dialogue.

“While, in the last three or so years my output has just been music, I’ve had other works going too. I have notebooks in which I probably draw more than I write.”

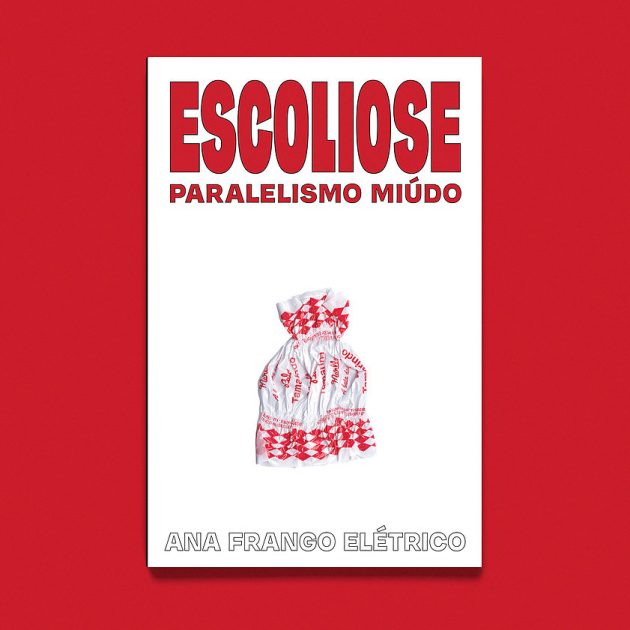

Redressing the balance is Frango’s latest release: Escoliose: paralelismo miúdo, a book, published by Rio imprint Garupa, that brings together poetry, prints and illustrations from 2015 to 2020. Flicking through the multi-coloured hardback, Frango tells me more.

“It’s part of a bigger search into my language: Portuguese words – and colours. There are three poems in here that became lyrics to my songs: ‘Roxo’ from Mormaço Quiema, and ‘Se No Cinema’ and ‘Torturadores’ from Little Electric Chicken Heart. And so this is a book that, maybe, once read, will allow someone to understand a little more about my universe that can be crazy but also ordinary, too.”

“Ordinariness” is, for Frango, at the heart of her inspiration: “I think my art has something to do with pop art and pop poetry,” she explains, while gesturing to the cover art: a crumpled sweet wrapper. “This is a tamarindo candy – a really, really sharp Brazilian candy. I love it – and, in the book, there’s a lot of sounds, colours and foods… Which are all ‘pop’ for me.”

I ask Frango to decode her abstruse title, which translates to “Scoliosis: Pint-Sized Parallels”, and, first tackling the alliterative subtitle, she gives more insight into her fascination with the “ordinary”.

“I sum up this sentiment best in a poem where I say something like: ‘your ceiling is the ground of the owner of your neighbour’s dog.’ There’s the parallel – what your ceiling is, for you, is something totally different for someone else. So it’s about ordinary little things that, once seen from a different perspective, become a bit different. It’s like taking a detour to view day-to-day life from a different angle.”

This “detour” is the curve-in-the-spine that becomes the title for Frango’s book (“Scoliosis”). But it just as well suits to describe much of our three-hour conversation which, led by an exuberant Frango, bounces and bends from one incongruous matter or memory to the next – always excitedly and sometimes incomprehensibly.

I ask the young multidisciplinary why Escoliose became a collection of different media – written poetry, visual prints, even song lyrics. Do you see these different arts separately, or always together?

“I experience them together a lot. Look at me! Look at my room!” Frango sweeps the camera from one corner of her bedroom-studio to the next. A white chest of drawers, absolutely blitzed with multicoloured scrawling, stands out, set off from bright blue canvas-covered walls. “I’m surrounded by all these colours – and sounds. I’m always listening to music and drawing and painting, and my girlfriend is a genius illustrator… So, I think very graphically: I think about music as colours and I use colours to communicate.”

What colours are your two albums Mormaço Quiema and Little Electric Chicken Heart?

“For me, Mormaço Queima is much more saturated – yellows, reds, purples… And like acrylic McDonald’s stuff. For Little Electric Chicken Heart, I had the idea of a deep blue album.”

Frango explores such synaesthetic associations in much of her music. The liner notes to Mormaço Queima identifies the debut album as “saturated with textures, tastes and colours”, and directs the listener to “eat something sharp and sweet (like a tamarindo candy)” while listening. Meanwhile, the lyrics to “Se No Cinema”, one of Little Electric Chicken Heart’s most dynamic cuts, begins: “Ah, if only in the cinema/ You could feel the temperature/ of love/ Of the couple on the screen, of her sex/ The smell of colour”.

“It’s got a lot to do with synaesthesia, that song,” Frango grants. “Little Electric Chicken Heart, for me, is about nostalgia. And I think there’s a lot of nostalgia sparked by smells.”

The sound-world of Little Electric Chicken Heart is imbued with this nostalgia. “It’s an album that, people tell me, evokes the seventies,” Frango recognises. “I think this is because it’s not a loud album – nor is it very compressed. There is a real big-room sound, and a tape sound that I really wanted: big-room drums, horns in every song and backing vocals…”

I prompt Frango to continue describing her sound – something she’s been reticent to do in other interviews.

“I was really listening to Nora Ney, this fantastic, beautiful singer from the fifties and sixties, and a lot of samba canção which is sad but kind and cosy too. I listened a lot to Burt Bacharach’s first album – and lots of Quincy Jones and Blossom Dearie. But mainly, I listened to Brazilian music.”

I suggest that the album shares an intimate tone with Rita Lee’s 1970 debut solo album Build Up.

“Build Up is a really big reference point, of course. Johnny Alf, Dalva De Oliveira, Jorge Ben’s arrangements… ‘Tem Certeza’ is rooted in Jovem Guarda musicians like Roberto Carlos, Erasmo Carlos… ‘Devia Ter Ficado Menos’ to me is really Os Mutantes, as well.” She sweeps up her guitar and plays the latter’s stumbling melody line, over-performing as if a member of the extremely eccentric and influential tropicália outfit.

Knowing her disinclination to be pigeon-holed as a member of Brazil’s MPB canon, I’m surprised how vociferous Frango is when rifling off her national influences – most of which belong to this música popular brasileira lineage.

“I don’t like MPB, I love MPB!” She retorts when I suggest as much. “I love João Gilberto, I love Jorge Ben, I love Caetano Veloso, I love Gilberto Gil, but this name, this signifier: ‘música popular brasileira’, ‘popular Brazilian music’…” She rolls her eyes, her exasperation palpable. “The popular music today is not guitar music. It’s funk, it’s axé, it’s many things that have names and are beautiful… So why is my music called ‘Nova MPB‘ [‘New MPB’]?”

“I just don’t assign to this idea of genre. Artists are like creative islands – like Tyler The Creator. You can’t give a name or genre of music to Tyler! We now live in a generation that has lots of access to musical information, so we are not one thing. It’s important to give the possibility to the artist to tell you what she does, you know!”

So what do you do?

“Mormaço Queima, I’d normally say is ‘bossa pop rock’. And Little Electric Chicken Heart is ‘ballad-rock jazz’. But, really, it’s not jazz, it’s not bossa, it’s not rock – what the fuck is it? I don’t know! It just doesn’t need to be something!”

Frango grins, a weight visibly lifted.

Zooming in on the opener “Saudade”, which Frango understands as a sonic and thematic overture for the ensuing album, I ask about its gorgeous piano intro. To me it sounds like Debussy…

“It’s [drummer, trombonist, and long-time collaborator] Antonio Neves! He was doing the arrangements and he played me this piano part which he initially wanted to transfer to horns. I love it because it has a lot to do with the main melody on ‘Saudade’.” Picking up the guitar, Frango skips through the piece’s doo-wop head melody and then the piano introduction, stressing their melodic similarities.

“I really like arrangements that discreetly give away melodies that will happen later. When you hear the main melody later, you already feel this nostalgia because you’ve heard an inversion of it before on the piano.”

Nostalgia, already stressed as one of Little Electric Chicken Heart’s primary themes, is further emphasised in the album opener’s title: “Saudade”, that famously untranslatable Brazilian feeling, the happy-sad complexity of which English equivalents such as “longing” – or, indeed, “nostalgia” – just fail to grasp at.

“I think that it’s this common feeling, this saudade, this nostalgia, this feeling of missing. And it’s happy as well as melancholic.”

It’s remarkable for such a young woman to find her creative wellspring in this collective nostalgia – this implacable yearning for a mirage-like past that, for Frango, only extends back twenty-three years. It’s characteristic, though, of a young woman, who often flits from kiddish charm to a keen wisdom far surpassing her age.

“I’m just twenty-three years old,” Frango reminds me throughout our chat, as if her opinions warrant some kind of disclaimer. “I don’t know a lot about what we’re talking about. I think I’m a work-in-progress. I have two albums and a book and many ideas for many things. But I don’t know what to say, because I’m just living!” She laughs somewhat sheepishly before conceding: “maybe I’ll say something that, when I’m 25 years old, will make me go ‘wow, you were a stupid kid!”

Her Grammy-nominated Little Electric Chicken Heart, though, has captured the imagination of critics and fans of all ages – including “the internet’s busiest music nerd”, The Needle Drop’s Anthony Fantano. The mood permeating the album’s music and words seems universal – substantiated by the album’s Japanese re-pressing. For Frango, this universality is underscored by the title.

“I already knew the name of the album before anything else – the same with Mormaço Queima. I know the names for my next three albums too!”

Why an English title?

“The phrase itself came from having a barbecue with friends. I was filming this chicken heart that was cooking and the phrase popped into my head. The idea of a ‘little electric chicken heart’ comes back to ‘paralelismo miúdo’: the idea that it is a teeny-weeny heart – inconsequential, but it is also ‘electric’, and it sounds big!

“I actually think the title is really Brazilian. My writing in English shows a Brazilian way of thinking in English. It’s all ‘love, baby’!” Frango giggles. “These are our words, too. We say, ‘I love you’. So, within the little-big idea, there’s a lot of humour – it’s a bit silly.

“But I think it stuck because it sounds like cinema.” Frango stretches her arms wide and repeats the name as if it’s up in lights: “‘Little Electric Chicken Heart’. Everyone around the world can understand that. I began thinking in a more cinematic way. And I was thinking about cover art that would show that. When talking to Caio Paiva, the artist who designed the cover, I was explaining that the name had to be on the cover, like really vintage.”

Paiva had other plans though. Doing away with the title, the final cover simply shows Frango spot-lit and close-up – in fact, so close to the lens that she’s out of focus.

“Instead, he really gave emphasis to ‘Ana’ and not to ‘Frango Elétrico’ [“Electric Chicken”]. And, in the end, I really loved that he saw the album as really intimate as well as cinematic. For me, it’s really difficult to expose my feelings, but on this album I think, less so in the lyrics, but in the sounds, I am front and centre: me, myself and I. I sing in a more closed way, and lower than on Mormaço Queima.”

Frango has always evaded intimacy within her art, lurking behind colourful characters, such as Nóia – an alter ego Frango invented while afflicted with a bad bout of mononucleosis as a teenager. The invention of Nóia coincided with her writing her first proper song “De Mim Para Nóia”. She attributes the term “noiada” to her compositions from that time. I propose that the inspiration for such creative role-playing might be found in one of her early musical icons: Hannah Montana. The suggestion is met with laughs and nods in agreement.

“Yes of course, it really has a lot to with this. I’m still learning to give space to this stage person – it’s really good to me.”

Latest single “Mulher Homem Bicho” (“Woman Man Creature”) gives space, instead, to the real Ana. Its lyrics, written by Frango’s friend and fellow alternative music trailblazer Ava Rocha, go as follows: “Não se assuste comigo/ sou mulher homem bicho” (“Don’t be scared of me/ I’m a woman, man, creature”). And, while penned by Rocha, the song’s story – which details Frango falling in love with a woman, and confronting her gender identity – is as personal as it’s got for Frango so far.

“I asked Ava, ‘could you give me Rita Lee lesbian lyrics?’” Frango explains of her single which, incidentally, sounds uncannily like Lee’s 1979 hit “Chega Mais”.

“I think I’m understanding my sexuality more and more, nowadays. And, that is what this song is about. I am in love with my girlfriend, a girl – not for the first time, of course, because a lot of girls have broken my heart. But, right now, I’m an open book because I’m living and I’m young and I’m discovering. Me and my girlfriend, we enamora – how do you say that in English? She’s my enamorada and we enamora…”

“Love each other?”, I suggest.

“Hmm… You don’t have a word…”

Frango, naturally, takes a lot of care over her words. The published writer’s exasperation shows throughout our chat when she can’t express herself as she might in Portuguese. But she concedes, now: “English is a much better language for non-binary people, of course. Portuguese is very binary…”

Do you identify as non-binary?

“I’ve never felt like a girl or a woman with pink everything – never, never, never in my life. I recognise a lot of masculinity in me and identify with men often. I really love the beard filter on Instagram, and when I started to have boobs, I was like ‘ugh’. But nowadays, I’m trying to get cool with my boobs. Maybe one day, I’d like to remove them, or maybe I won’t – maybe it’ll be fine, you know. I don’t have to push myself, though – I am Ana Frango Elétrico and that can be male or female or anything. Removing my paternal surname, and being more or less genderless, it gives me the comfort of being whatever I want at any point.

“I have a girlfriend. I have had boyfriends. So I don’t know… I believe that fluid sexuality and fluid possibilities and identifications are natural. This is what ‘Mulher Homem Bicho’ is about. And Ava was really ingenious with capturing all this in the lyrics.”

Was it strange having your friend write about such a personal topic?

“Well I trust Ava a lot. And, also, I think the most beautiful songs are those that anyone can sing and think ‘this is my song’. I’m really interested in making more songs like this as well, because my research nowadays is much less rooted in lyrics. I’m thinking a lot more about production, harmony and melody.”

Frango has always shared production duties, since learning the ropes on Mormaço Queima. But, following Little Electric Chicken Heart, which she co-produced with Martin Scian, she’s focussed on production more than ever. Her latest two singles “Mulher Homem Bicho” and “Mama Planta Baby” were produced single-handedly.

“I really like studios,” she confesses. “The studio part is what I enjoy most about being a musician – recording and building an album. I don’t really have a home studio, but during quarantine I’ve begun putting things together – a drum machine, monitors, some good plug-ins… I think at the beginning I didn’t hear sounds separately, but nowadays I pay a lot of attention to the sounds of instruments, the frequencies, the timbres… So, the two singles I’ve released during quarantine have been important. I’ve been able to produce and take care of the sections on Logic, making a pre-mix with volumes and stereos that I wanted.”

The importance of this, for Frango, extends beyond her aesthetic concerns though.

“It’s a real marker for me, because in the past women’s role in Brazilian music was constrained to singing songs written by male songwriters. Nowadays, it’s a lot better – there are much more possibilities and no fear in producing, composing and writing for ourselves… And women can sing, too. But we can also be more than this. You can be non-binary and trans – this is the possibilities of being woman.”

Frango’s fledgling career as producer has begun to take flight recently. Two projects she produced in 2019 will be coming out this year: an EP she co-produced for Dora Morelenbaum, and the debut album for the band Sophia Chablau E Uma Enorme Perda de Tempo.

“I’m really excited,” Frango exclaims. “These were my first experiences of producing things that are not mine, and the two girls are my friends, so it was so great. And now I’m producing a song for the Bahian singer Illy, and a compact, and some other stuff, and Dora’s asked me to produce her album… It’s funny, at the beginning of 2020, I was like ‘invite me to produce, everybody!’. But now I don’t have a lot of time!”

Despite an extremely busy schedule, Frango has also found time to return to her first band Almoço Nu, with whom she has been quietly releasing music since December: first, “Em Mangatada”, and then “Consipração Da Teoria” – the second oldest song in the Almoço Nu repertoire, which Frango wrote about a cockroach revolution.

A mere three years since releasing her debut album Mormaço Queima, Frango is returning to duties with her school band as a far more mature musician – due, in no small part, to her experiences playing and learning from an older generation of Brazil’s avant garde.

“When I started to play as Ana Frango Elétrico, it was always around people who were older than me – the Quintavant collective, like Negro Leo, Ava Rocha… And that was when I was really like ‘I wanna do this’. Ava’s second album Ava Patrya Yndia Yracema was the album that really made me go ‘woah, woah, woah’. It was an exercise in attention – paying attention to the bass, to the percussion, the layers… I was hearing stuff I hadn’t heard before.

“So, I’m not the young one anymore!” Frango grins. “There’s lots of people younger than me, making really good and different things – like Sophia Chablau.” She pauses. “Then again, I never felt my age – I have sixty-year-old women who are really my friends, senior ladies who are really my friends, too.

This month Frango will be premiering a new video for the Little Electric Chicken Heart song “Promessas E Previsões” on Aquarium Drunkard. Her admiration for the Rocha family extending beyond Ava, the video will be directed by Ava’s mother Paula Gaitán – who has previously, among other works, directed a documentary about Negro Leo.

“She’s a really amazing director,” Frango eulogises. “I began talking to her through Ava. But I hadn’t realised I’d already known her before then because I’d seen Super 8, a movie of hers which was really amazing. I asked Paula to make the video with a personal touch. And, instead of me appearing in the video, it’s just Paula being free with the archives from Super 8. To me, this has a lot to do with the album because of that sense of nostalgia; this is where I knew her from at first.”

“I think it’s important, too, because she’s an older woman that I respect. And I respect her work so it’d be cool to bring her work to younger people.”

Considering she’s an interdisciplinary artist who has just released a book of poetry, talk of lyrics is conspicuously absent for much of our conversation. I press her to analyse “Torturadores”, one of the songs whose lyrics has been published in Escoliose: paralelismo miúdo. Sonically, it’s one of Little Electric Chicken Heart’s cutest cuts, with a gently lolloping rhythm section underpinning breathy vocals and twinkly guitar plucks. Remove the music though, and these lyrics are anything but cute. The words are an arresting response to the torturing which, carried out by members of Brazil’s military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985, has been frequently endorsed by current President Jair Bolsonaro.

“The song has a lot to do with the current government,” Frango explains. “We have politicians in charge who are talking about these tortures and about AI-5, which was the legislation in the sixties that allowed things to get so ugly.

“But I wrote this song after hearing a story about the wife of a Brazilian singer who had been arrested. The police came to her house and arrested her too and she was tortured. Then, six years ago, she was in a supermarket and she saw her torturer. After this she got panic attacks and depression.

“Within Latin America, Brazil is one of the countries that doesn’t have this resolved – we don’t know the names of the torturers, you know. Like who are these torturers? Where are these torturers? They are alive, and fuck that he’s 80 years old, I don’t care. I think that we at least have to know the names and addresses – it’s the least we deserve. Those names that we do know are being commemorated by our president… It’s a horror.”

She pauses, contemplative. It’s a rare moment of silence for the often animated young woman.

“Maybe I speak about it less than I should, I don’t know… At the same time, I’m not the right person to talk seriously about this stuff. I don’t speak a lot of politics but I’m a political person. There’s a guy I really love in Brazil called Jones Manoel, who’s a current writer and Marxist. He has an amazing precision when talking about communism, and he stresses how neo-colonialism is fruit of capitalism. Capitalism kills a lot of people every day. Ok, communism has killed people but it’s helped in a lot of places: in health and art and politics, in ways which capitalism doesn’t even think it experiences… We’re a really rich country and we just have the worst president ever that doesn’t have anything to contribute to society.”

Her dejection fades as the corners of her mouth curve into a smile. “Now, you guys are a bit better, but–”

I interject, exclaiming how embarrassing it is to be from a country led by Boris Johnson, but Frango, now loafing on her bed, laughs it off.

“Relax, because Brazil wins at this… We can’t even enter anywhere now.”

Frango continues from airing this grievance with a startling revelation, which she affixes nonchalantly, as if adding minor detail.

“It’s annoying because I have to go to New York to record an album at Electric Lady Studios, but I don’t know when I can enter the U.S. anymore.”

I start at this remarkably casual announcement: Electric Chicken at the Electric Lady Studios. It’s a mouth-watering prospect, worthy of a whole interview itself. But Frango continues like this revelation’s nothing, too engrossed in the technicalities of recording to see the big picture.

“It’s going to be all analogue and vinyl sounds,” she enthuses. “We’ve got to go in and do it in seven days, so I have all the concepts already built. I had moments where I wanted to do something really different to Little Electric Chicken Heart but it’s going to be fairly near, sound-wise. It will do some other stuff too, though. There’s always things I want to keep and also stuff I want to evolve. This album in particular has to be done at New York because the space has a lot to do with this sound and this idea.”

Frango is effervescent with ideas. Wide-eyed, she seems already transported to the studio. “It’s really good, I want this so much.” She beams, her enthusiasm overflowing. “I really want to do something with muted horns and flute, and I really want to record organ. I hear so many sounds that make me go, ‘hmm, I really want this, I really want that!'”

Compelled by seemingly limitless creative impulse, Frango hardly stops for breath as she rifles through various sounds, equipment and arrangements that she wants to work with. When exhausting her list, she seems as tireless as ever, already looking towards the next project. She stops and smiles, looking towards a horizon that keeps stretching out before her. ” And, then, after this,” she announces, “I’ll go on and do something completely different.”

Escoliose: paralelismo miúdo is out now at Garupa.

Little Electric Chicken Heart and Mormaço Quiema, as well as singles “Mama Planta Baby” and “Mulher Homem Bicho” are out now on Selo RISCO.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.