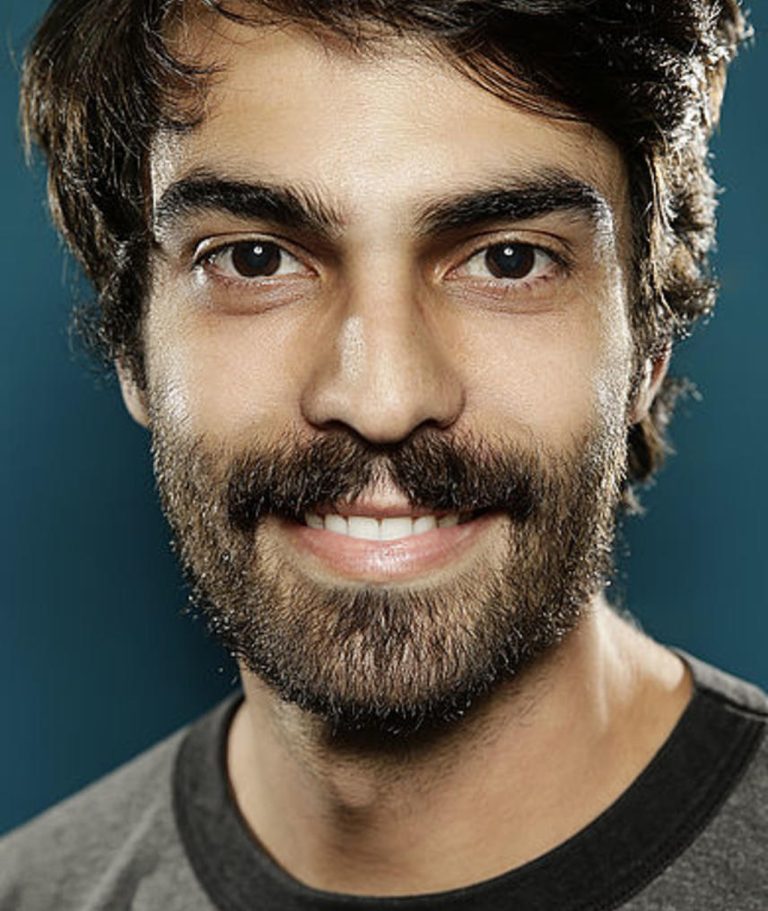

‘Cinema Was An Important Refuge For A Kid Who Understood That The World Wasn’t a Safe Space For Being Queer’: An Interview with Brazilian Director Gustavo Vinagre

27 June, 2022Gustavo Vinagre is a Brazilian film director and screenwriter, who aged 37, already has 19 productions under his belt – including series, features and short films. His most recent film, Three Tidy Tigers Tied a Tie Tighter (Três Tigres Tristes, 2021) won the Teddy Award for the best queer film at this year’s Berlinale, and will be shown later this week at the Barbican Cinema’s Forbidden Colours – a programme which celebrates rarely seen queer-focused films from places where LGBTQ+ people still suffer societal oppression and struggle for equality.

Three Tidy Tigers Tied a Tie Tighter follows three young queer characters living in São Paulo amidst the fourth wave of a pandemic, which makes people suffer from memory loss. Sounds and Colours spoke with Vinagre via email ahead of the screening, and his thoughtful responses can be read in the interview below.

What triggered your love of films and the desire to be a film director?

That’s a tough question. I think it has always been the possibility of reimagining the world. To me, growing up, cinema was an important refuge for a kid who just felt really awkward and who understood that the world as it is/was, wasn´t a safe space for being queer. I was also influenced by my cinephile older sister, who was always showing me cool films, and making me think about them.

You’re a very prolific film director, with 19 productions under your belt. Can you tell us how you’ve been able to make this extraordinary number of films in a period of less than 15 years?

I think that is crazy. And it also has to do with some privileges… being a middle-class cis (for Brazilian´s standards) white man allowed me to have some stability in my life. But, of course, not only that. I also create my films from a production point of view, making very simple choices that will allow me to shoot with a small crew, and in a really short amount of time. When I left cinema school, I decided that I needed practice, and If I wanted to become a filmmaker, I should make films, good or bad. So that´s what I did, all kinds of film: fiction, documentaries, porn, with a cell phone, in one night, in three days, in a month. Most of them with close to zero budget and the help of friends; a few of them financed by my country’s cultural politics.

What other Brazilian film directors of your generation do you consider to have a similar guerrilla approach to filmmaking, and which of their films would you recommend?

I mean, to make cinema in a country that is actually killing its own people – black, indigenous, trans, queer, poor – daily and defaming its artists, is always a guerrilla activity. I would recommend films from Lincoln Péricles (Filme de Aborto), Caetano Gotardo (Seus Ossos e Seus Olhos), Adirley Queirós (Branco Sai, Preto Fica), André Novaes (Temporada), Marco Dutra and Juliana Rojas (As Boas Maneiras), Fábio Leal (Seguindo Todos os Protocolos), Julia Katharine (Tea For Two), and so many others.

When it comes to accessing independent films in Brazil, how can audiences go about rather than through film festivals? Are streaming platforms welcoming to these productions after they’ve been shown in festivals?

It’s a really hard process. Most of the films are confined to the festival circuits – and I am so thankful that at least festivals exist. Unfortunately, it is very hard to be on a streaming platform – maybe easier in the more artsy ones – because most of them are just based on audiences and mainstream taste, and conform to standards of what companies think cinema should look like. Also, inside Brazil it’s a huge struggle because going to the cinema is so expensive and, when people actually get to go, the cinemas are basically showing only American films that have a huge investment in their distribution. So, it is not a fair competition at all, and we are a country that is not really used to seeing itself on a big screen.

Besides directing Three Tidy Tigers Tied a Tie Tighter, you also wrote its script – alongside Tainá Muhringer. Where did the idea for this film come from?

This film’s first script was born in 2016, since then we had four versions, each totally different from each other. The last one, finally, embraces the pandemic, because that was the context we were living in, and to me it didn’t make sense to make a film inside this situation pretending weren’t in it. So, that really changed the whole story, and that plays a very important role inside the film’s narrative. But I think what all versions had in common was this idea of playing with a sort of naive feeling, I just wanted it to have this childlike vibe. I wanted to have a light perspective of some hard subjects, and try to create this world in between – between childhood and adulthood, serious and comical, realistic and theatrical, sweet and bitter sweet.

The film has been described as “queer cinema at its most radical”. Were there any artistic works which inspired you to approach this story like you did?

I think radical is a really open word – it depends a lot on the viewer. I mean, I have some explicit films that would be easily considered much more radical than this one, depending on the point of view. For this film, I had four films that inspired me, especially because I think they have a magical feeling of naivety to them, although they are really different films when they are compared to one another. They are Harold and Maude (Hal Ashby), Tampopo (Juzo Itami), House (Nobuhiko Obayashi), and A Dança dos Bonecos (Helvécio Ratton).

The film is filled with very timely social commentaries – for example a scene where one of the characters drinks from a baby bottle with a penis-shaped teat, which in real life was part of a fake news video that circulated in Brazil about an alleged “gay kit” that left-wing political party PT was supposedly distributing to nurseries. What is the message you hope they will help the film convey?

I am not sure about the message; I think it can be read in different ways. Maybe it’s pointing with sarcasm to the political absurdity we are living in. Maybe there is some other possible hidden message: I’m always really open to hearing from the audience what they think, that’s why festivals are also so important. They are a place of interchanging ideas, and I actually learn a lot about the films I do by listening to other people’s opinions. There are things you put unconsciously in a film, and that only become rationalized after some screenings and Q&As.

The film score includes the antagonistic sounds of a piano — with music from late 19th century Brazilian composers such as Chiquinha Gonzaga and Ernesto Nazareth — with synthesisers. Why this choice?

Well, it’s a film about memory and the loss of memory. We thought about bringing back these classical pieces and making the audience listen to them in a different way. The soundtrack by João Marcos de Almeirda was really inspired by Wendy Carlos’ A Clockwork Orange soundtrack. And, of course, we did not have to pay anything for it because they are in public domain – an example of what I said before about adjusting your creation to your budget.

The film includes a very evocative cabaret sequence in which all the characters — alive and dead — are reunited to see a live performance during the fourth wave of a pandemic, which causes people to suffer from memory loss. What does that sequence symbolise in the film?

To me that scene could be about creating a common space for freedom, memory, queerness, embracing utopia, but accepting its impossibility. It’s about embracing paradox, really, accepting failures… I mean, there is some kind of freedom, but there is still pollution, there is still capitalism, there is still fake news. But there is also music, re-encounters, loving objects in a transcendental way, and friendship. So, who knows? I want to figure that out also.

Do you have any upcoming projects that you can tell us about?

No. I would like to watch more films, read more books, and make more love.

Three Tidy Tigers Tied a Tie Tighter is showing at Barbican Cinema on Friday 1 July 2022 at 6.20pm. Tickets can be purchased in advance through their website.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.