Dedication On A Micro-Budget: Alexandre Moratto Talks About Debut Feature ‘Socrates’

04 September, 2020The Brazilian film Socrates (2018) is released in cinemas and on streaming platforms in the UK on Friday 4th September. Its director, Alexandre Moratto, found a break to speak to Sounds and Colours about his first feature whilst working on the post-production of his newest project, which he finished shooting before the quarantine. About his debut film, he says,

“[Socrates] has been the centre of my life and it’s been a lot of work to get it out here. I got it off my chest and it feels wonderful. It’s a massive relief – that’s how it feels.”

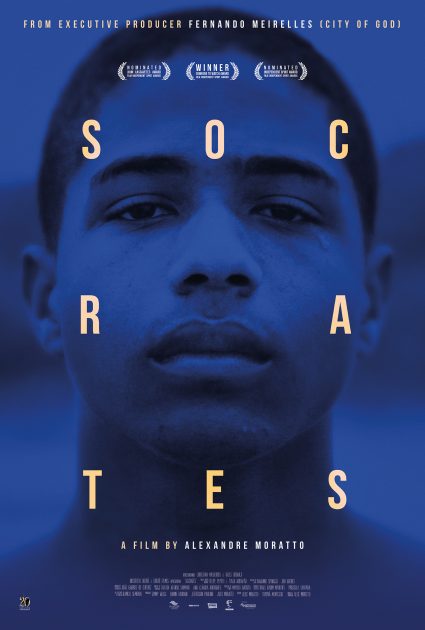

The film tells the story of a gay black teenager in Brazil, facing homelessness and discrimination for his sexuality after his mother’s sudden death. It is produced by Ramin Bahrani (winner of the FIPRESCI Prize at the 2005 London Film Festival for Man Push Cart) and Querô Institute, a UNICEF-supported charity that provides social inclusion to teenagers from low-income communities through film-making. The film’s Executive Producer is Fernando Meirelles (Best Director nominee at the 2004 Academy Awards for City of God). Shot with a micro-budget of under 20,000 US dollars, the film has collected 17 award wins and 13 nominations so far.

Christian Malheiros, who plays the character that the film is named after, is exceptional in his first role, which gave him a Best Male Lead nod at the 2019 Independent Spirit Award – Moratto took home the Someone to Watch Award that year. The actor has seen his popularity grow since the film was released, landing the main role in the Netflix hit series Sintonia (2019), the Brazilian production which recently debuted its second season.

It is a major accomplishment that Socrates got made and equally amazing that it is being seen around the world. Yet, it is not an easy film to like. The camera movements can sometimes be too hard, even for a story increasingly aggravated by prejudice and neglect. The suffering of the main character is excruciating and at times so hurtful to watch that it desensitises you. Any resemblance with real life is no mere coincidence here, both on the screen and in front of it. Causing such a strong reaction that makes one dettach emotionally is no easy feat nowadays though. It’s important to consider what that says about the film itself, but even more pressing that we try to assess what that says about our humanity.

Below is the interview Alexandre Moratto gave via video call from his home in the USA.

Can you tell us a bit of your Brazilian-American family background?

My mum was Brazilian and she did graduate school in the US. She met my dad and then they got married and had me. My mum stayed in the US, but she wanted me to have a lot of contact with her family – she was very close to them. I would go to Brazil with her about once a year for a couple of months. She was a teacher, and because I was growing up, the time our schedules would align would be during summer vacations. Then I did six months of high school in Brazil, and during college I wanted to get to know the country better and spend more time there. I’ve always been a dual citizen, but I’ve lived more in the US and did most of my school here. Now I just come and go a lot.

What got you into films in the first place?

I would watch a lot of movies with mum. Lots and lots of movies. That was what we would do. She’s from São Paulo, a very cultural city: people love film, arts and culture. So she raised me with that. Before being a teacher she worked in culture, so I guess she surrounded me with that. It’s just something we would do every day, back when we would watch movies on VCR, and then it was DVDs, and then we’d go to the movies occasionally. So I grew up watching lots of movies – she had a really deep respect for them. She would read what the critics would write and she would show me reviews by her favourite critic, David Ansen from Newsweek magazine. So I grew up reading his reviews, which made me understand not just the experience of watching a film, but from a critical standpoint what makes it interesting and what are the things you can talk about. Now he is a friend; I actually met him. He runs a festival that my film screened at and I’ve known him for a few years now. He’s been just wonderful.

Did you then go to film school?

I did. I knew I wanted to make films. At one point I didn’t know if I wanted to be a critic or if I wanted to make films. I felt like I had things that I needed to say as an artist or as a person, so I felt that the better decision for me was to make films. I went to UNC [University of North Carolina] School of the Arts. That was where I met Ramin Bahrani, the great film-maker. He was making his fourth feature, Goodbye Solo. I worked as his assistant. I was with him for maybe four or five months, every day. We just really got along. He saw my short films, my student films, and I think he sensed that, for lack of a better word, there was a voice there that needed to be nurtured. But that I needed to learn how to write a script and how to tell a story. So he really put me through film-maker bootcamp and I learned a lot with him. He kept nurturing me. Throughout college we kept in touch, and after I graduated he would read my scripts, work with me on them and help me bring what I wanted to life. He’s been there with me every step of the way. He is a producer on Socrates and he is producing my new film too, which we’re working on.

The film is dedicated to your mother. Is the story in any way inspired by your own experiences?

Sure. Lots of it. It’s not an autobiographical film – and I didn’t want to make one. But I’d gone through something very tough when she passed away, and her illness leading up to her death too. It was a really really tough moment for me: financially, personally, emotionally. It was a very isolating experience because she was in the US and her family was in Brazil, and my parents are separated. I was with her through those last couple of years. I felt like I needed to express what I’d been through, so that found its way into the film but in a totally different context from my own. And I wanted to make the film with Instituto Querô because I’d volunteered with them when I was a film student. I was 19 and I spent three months with them during one of the summer vacations.

What took you to Querô Institute in Brazil?

I was in my third year. I was 17 when I went to film school. I was really young because I skipped a grade. When I was 19 I went to Brazil and spent 3 months with them, which was really an incredible learning experience for me. I became friends with them and it was just wonderful. They were so nice and they showed me their world, and I told them what I knew about mine. So it was very much an exchange in that sense. I was a volunteer. I would go to the sets with them and we’d discuss film and I’d help them out, things like that. They just really embraced me. We had this dream that maybe one day we’d make a film together. For years we kept in touch but I just never found the right project. After my mum died I went back to Brazil to spend some time there with family and I reconnected with them. The feelings of the script were already in my head and being there on the ground again I sort of saw the way I would want to do it.

What inspired you to tell the story of Socrates?

Some of the students of Querô Institute identify as gay, so I’d heard some of the stories of their experiences. Something I found very strong and important. I started thinking about what it would be like to be really young, lose your mum, cut off from your family, in really difficult circumstances… what sort of strength you’d need to summon to survive. Not just the survival of paying your rent and putting food in your mouth, but how do you emotionally survive that. Because, see, that’s even the bigger tragedy than inequality and poverty, the lack of love towards so many people. That was the feeling I was trying to capture with this story. That’s how it started to come together. The first draft of the script came together very quickly, I wrote it in like a week because I had so much bottled up inside me. Then I presented it to the Institute and they loved it. I re-wrote it with Thayná Mantesso, who’s one of the young people from the programme. She was 18, [she had] great ear for dialogue, [she was] born and raised there. She brought a lot of authenticity to it, but she was also very talented. She has a great vision as a person and as an artist. She was quite a find for me. I was very happy that it worked out for us to rewrite that script together. The whole thing happened so fast. I had the idea to make the film in December 2015, in January I already had the script, in February we were greenlit by the Institute and by August 2016 we’d already filmed almost everything. We saved some budget to do pick-ups later. We were shooting in a sort of improvisational way, so I sensed we would probably wanna shoot more later, which we did a little less than a year afterwards.

When did the Executive Producer Fernando Meirelles come about in this process?

Fernando got involved when we were in the finishing stage. 02 got involved, [the production company which Meirelles co-founded, one of the largest and most prestigious in Brazil], because we did our finishing with them. Then 02 Play picked it up for distribution. Igor Kupstas, who runs the latter and is a very great sales agent, presented the film to Fernando and asked if he wanted to come onboard and help the film get more visibility. He loved it and said yes. So that’s how it all came together. Ramin [Bahrani, main producer of the film] and Fernando [Meirelles] are my heroes. If you’re lucky, sometimes you get to work with your heroes. That’s really special when it happens. I feel very blessed.

The film was shot with a micro-budget of under 20,000 US dollars. What would you list as the peculiarities and the perks of filming with such a reduced budget?

I didn’t make it that way because I wanted it. I made it with a micro-budget because for five or six years I tried to get funding to make a movie and all the grants, all the editais [a type of funding in Brazil, given by private companies through the government for tax incentive], all of the private investors said “no” to it. Being a film-maker is such an important part of my life, it’s kind of central to who I am as a person, so when you hear “no” every day for that long, it feels like a lot of doors slamming in your face. You start to question your self-worth. In a lot of ways, every time a door slams in Socrates’s face, that symbolizes how it felt when you sacrifice everything to try and get out there… this is not news, it’s what many film-makers go through. Many of them quit. You have to have a lot of stamina to put up with a lot of “no’s” like that and still think you’re worth it somehow. I made it with that [amount of] money because no wanted to give me money. I told the Institute that I thought I could do it through crowdfunding. In the end I didn’t have to. I’d been working and saving up, so I put a little bit of money in, then friends and family gave me U$500 or U$1,000 here and there, so I just put all in a basket and took it with me to Brazil. The Instituto understood the zero-budget idea behind it. Everybody worked for free. And boy, did they work! It’s a product of a lot of dedication. We didn’t have any money but we certainly had a lot of passion. They’re so proud of the film. By the end of filming they were professionals – it was amazing.

Socrates is screening in select UK cinemas and is available to stream on Curzon Home Cinema, Vimeo On Demand and BFI Player.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.