Sounding Out the Swamp: Recife, Pernambuco, and The Cultural Rise of Northeastern Brazil (Part Two)

19 September, 2011In the second part of Sounding Out the Swamp: Recife, Pernambuco, and The Cultural Rise of Northeastern Brazil (read part one here) Gregory Scruggs looks at how manguebit affected the musical landscape of Northeastern Brazil, starting with the question “What does the post-mangue era look and sound like then, when Recife is neither so desperate nor so isolated culturally?”

Helder Vasconcelos, who played in Mestre Ambrosio, one of the other mangue originals who did to forró what Nação Zumbi did to maracatu, met me at the Livraria Cultura in Recife Antigo. He explained that on their first tours, the band travelled with a Pernambuco flag, because localising themselves not just as Brazilian (when touring abroad), but as specifically from this corner of Brazil, was vital. Nowadays, that is less of a concern. “In music, there are no more borders, those are political distinctions,” Vasconcelos argues. Likewise, “We don’t think any more in tradition and modernity, just in music.” As the current generation of Recife-based musicians interacts with music both old and new, the space to experiment opened by mangue is essential. No different, Vasconcelos claims, than the legacy of tropicália on his generation.

Pedro Farias, a young researcher at the Chico Science Memorial, a freshly renovated colonial-era townhouse that gives onto the Pátio São Jorge, downtown Recife’s principle outdoor stage, sat down with me to speak about the mangue legacy and contemporary Recife. “Pernambuco is known nationally now, far beyond Luiz Gonzaga [a composer and musician from the state who became nationally famous in the 1940s for his baião and other country rhythms],” Farias explained. “The scene is very rich and much more concerned with assimilating and protecting northeastern rhythms.” He rattled off a list of names, from Johnny Hooker to Orquestra Contemporânea de Olinda to Academia da Berlinda to DJ 440 to the Lumo Coletivo – all musicians, artists, and producers operating in the milieu pioneered by the image of an antenna protruding in the mud.

Nowadays, Vasconcelos says, the more appropriate image would be a mobile antenna popping out of a backpack, as digital culture simply did not exist in the heady days of the early 90s. Dolores agrees, his eyes getting wistful when he speculates on what he and his compatriots could have done with PCs and sampling technology. In the early 2000s, with such equipment finally in hand, which he called “a door to the world,” he produced a multi-instrumental blend of northeastern music with an electronic overlay under the name Orquestra Santa Massa, and later mounted a band to perform the album live.

Orquestra Santa Massa reunited this year for a series of live performances, including an electrifying April performance at Rival Mais Tarde in Rio de Janeiro and a 7am sunrise stomper at São Paulo’s all-night Virada Cultural (below is a video of the group from 2002). The infectious and energising show synthesizes fiddle, trombone, drum ’n’ bass, and the stirring vocal style of northeastern ciranda singers. When asked what exactly is the je ne sais quoi of Maciel, the son of Mestre Salustiano, who sings in the current incarnation of the band, Dolores smiled and shook his head: “Just a beautiful voice.”

The relative success of Santa Massa aside, Dolores acknowledges persistent challenges in the dissemination of Pernambucan music to other parts of Brazil, even 20 years after mangue’s splash. Earlier this year, Circo Voador, by far the most diverse and open-minded live music venue in Rio, brought him to DJ between sets by two local living legends, Lia de Itamaracá and Dona Selma do Coco, for the debut of a new event, Coisa Nossa, which intended to showcase lesser known Brazilian music and musicians. But the very fact of someone like Dona Lia exists outside the record industry sunk the chance for an audience, and the empty house made the first edition into the last. At the same time, the Brazilian press didn’t fail to note that fully a third of tracks on the compilation Oi! A Nova Musica Brasileira! were from Pernambuco, as music critic Carlos Albuquerque wrote in his January review for O Globo.

Ultimately, Dolores believes that if mangue is not the creative model of contemporary Recife, then its DIY spirit remains powerful. Vasconcelos points out that the band Mombojô was one of the first in Brazil to give away mp3s for free on its website, and mangue originators Mundo Livre S/A (the name, Free World Inc., already speaks volumes) recently headlined the Digital Culture Festival in Rio, an event very much ideologically in line with the copyleft movement and ideas likes Creative Commons and free culture. Vasconcelos also sees mangue’s influence in one of Brazil’s most noteworthy contemporary cultural scenes, the Circuito Fora do Eixo (Outside the Axis Circuit).

Emerging from Cuiabá, the unassuming capital of Mato Grosso – its dubious claim to fame is a reputation for being the hottest city in Brazil – Fora do Eixo has steadily caught underground fire over the past several years as a new platform for Brazilian indie and alternative rock music. The network now extends across several cities far from the economic, media, and cultural poles of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. In fact, it has become so successful that there is now a Casa Fora do Eixo in, of all places, the eixo: a live music venue in São Paulo. With Internet access, Vasconcelos affirms, the mangue artists of the 90s would absolutely have done something similar.

Crisscrossing the Interior

Despite interconnectivity – Farias told me that everyone his age in music has a home studio with a PC and some bootlegged software – Dolores remains a bit jaded, believing that the social phenomenon in Recife is more interesting than the music itself. He also views the city as isolated from the interior, the hundreds of kilometres that extend away from the coast. For all of Brazil’s leaps and bounds in economic growth and national development, a small town in the sertão (dry backlands), a four-hour (or more) bus ride from Recife, can seem markedly removed, culturally and socially, from the capital.

For one perspective on musical life in the interior, I spoke with Gregg Mervine, a percussionist who has been living in Monteiro, Paraíba and a member, among other ensembles, of the group Old Goats, which plays work songs from northeastern Brazil. On the one hand, Mervine explains, “You have people who lived before the days of radio and electricity, so they remember how to make a party with pifanos and drums.” On the other hand, he cites a local soundscape with forró of all kinds (traditional to electronic), brega, and electro-pop. “The northeast interior is going through a huge transition culturally and what’s emerging is really interesting,” he asserts, continuing, “There’s also a discourse in the cities and the interior, which borders at best on obnoxious and at the worst on fascist, about having to protect the roots and identity.”

Potential paternalism is always a fraught issue when classifying, and ossifying, music as “traditional.” One organisation that has taken the issue head-on, however, is Outro Brasil Music. A record label and booking agency based out of France, Outro Brasil has been one of the strongest proponents of Pernambuco abroad, releasing albums and promoting tours for the likes of Silvério Pessoa, Seu Luiz Paixão, and Coco Raízes de Arcoverde since 1998. For them, connecting the interior and Recife, which serves as a jumping off point to Brazil and the world, is a fertile aspect of contemporary Pernambuco culture.

Director Marc Régnier was kind enough to put me in touch with Renata Rosa, who lives in Olinda, a UNESCO world heritage site on account of its cobblestones and colourful colonial-era houses. During Carnival, the narrow streets are jam-packed as the twin cities of Recife and Olinda hold their own against Rio and Salvador, the stalwarts of Brazil’s pre-Lenten chaos. She has been coming and going from her native São Paulo since 1996, but several years finally transferred her voter registration, which told her family the decision was final: Olinda was her new home. In a gorgeous, spaciously appointed house – she believes it dates back at least 150-200 years – Rosa and I had a late afternoon cafezinho and discussed her musical trajectory.

“I’ve been singing since I was a kid,” she began, recounting her childhood in Brás, a working-class São Paulo neighbourhood where she befriended a neighbouring family, the Suiras, with indigenous roots. Soon she began passing her school holidays in Tchydjo, a village in the interior of Alagoas, where the family had relatives. “Everyone is a singer there, and they have a culture of polyphonic vocals,” Rosa explained. Over the years she trained her voice the same way, which soon got her into trouble in formal music school, where she was told it would harm her voice.

That kind of prejudice wasn’t unique to her musical training. Rosa laughs incredulously when remembering the story of Siba, another ex-member of Mestre Ambrosio, at his first Brazilian musicology class in Recife. The professor cavalierly declared, “The blacks only make batuque [music for Afro-Brazilian religious ceremonies] and the Indians don’t have any musical tradition, so we’ll begin with Mineiro baroque,” a European tradition adopted by the Brazilian elite during the gold era in Minas Gerais. So much for the Freyrian argument of enduring African influence on Brazilian civilization. This was some time ago, however, and today the Federal University of Pernambuco boasts an ethnomusicology nucleus, founded in 1997, with a bit more respect for its surroundings.

Undeterred, Rosa became an ardent student of the northeastern interior. The neighbouring village to Tchydjo had some serious rodas de coco and Siba introduced her to rural maracatu. She ultimately became a contra-mestre in the Zona da Mata, the forested region between the coast and the dry backlands. Her experience in the Zona da Mata in part led to her debut album, Zunido da Mata (listen to a track from the album below), which won the 2004 Choc de l’Année award in France and bookings at Womex. She won the Prêmio da Música Brasileira in 2009.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2UeSnvTPZrc

Working with old-timers like Seu Luiz Paixão, a renowned fiddler whose album Pimenta com Pitú (Pepper with Cachaça) Rosa produced, is “an exchange that’s like a broth, a culture in two sense of the word, the traditional and also like a yoghurt culture.” Olinda also has a serious concentration of artists, and, she believes, “The informal encounters are where this broth comes from.” Historically, meanwhile, she believes, “If it were not for the mangue movement, I wouldn’t have stayed here.” For someone raised in the country’s cultural epicentre but with an interest in Brazilian roots, Recife in the late 90s was a kind of clarion call.

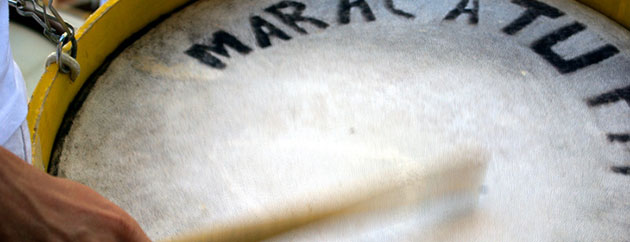

Its an attraction that persists today, with contemporary musicians, producers, record labels, and the like the beneficiaries of a massive history and an evolving present. Helder Vasconcelos, in his typically energetic fashion, marvelled when I asked him about Carnival in Recife. “It’s a locura de tradição [insane amount of tradition],” he repied, rattling off boi, maracutu, afoxé, samba, and frevo, before turning to caboclinho, a Carnival folk dance, and explaining that alone has five different rhythms to it, then more or less so does everything else. The multiplication was both overwhelming and exhilarating.

Gregory Scruggs is a freelance writer, DJ, and urban researcher who lives in Rio de Janeiro. He focuses on the intersection between audio culture and urban space.

Plus, listen to new music from Pernambuco via our compilation Musica da Massa! New Sounds of Pernambuco and also check out our In A Nutshell guide to the Mangue Bit movement: In A Nutshell: Mangue Bit.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.