Chapter 3: Que Bonito es el Turismo

10 August, 2016Day 3 / 3rd May 2016

The housekeeper at Casa Marmol offers me breakfast of an omelette with ham, toast, tropical fruits and coffee so strong, it keeps me wired all day.

After some WiFi time at Plaza Céspedes, I head to Sala Dolores, where I was told Ariwo will be rehearsing and again run into Aaron Liddard, who’s headed there too. While hanging out inside the rehearsal room watching the band I realize that I am very content to be where I am at that moment, witnessing the creation of entirely new forms of music drawn from at least four different historical sources: Persian music, electronica, Afro-Cuban and jazz. This is, after all, the whole point of Manana: to bridge cultures and generate forward-thinking electro-folkloric musical collaborations between Cuba, the UK, Europe and the Americas while simultaneously honouring and spreading awareness of older Afro-Cuban music.

Aaron Liddard, Saxophonist & Stand-Up Gent

Yelfris, Noda and Hammadi from Ariwo

I break away to catch the tail-end of the festival’s official opening ceremony speech at Teatro Herédia, a mixed bag of Cuban propaganda and arts advocacy with Alberto Lescay, Manana ambassador and designer of the massive sculpture at the nearby Plaza de la Revolución. The plaza sculpture, which is the largest in the country, depicts Santiago’s native son and hero, Antonio Maceo, sitting atop his horse in front of 23 huge machetes that look like an abattis designed by Richard Serra. When I wander off to explore the Teatro Herédia complex, I discover that there is no running water in the bathrooms and no flushing toilets, which is a bit worrisome given the hundreds and maybe even thousands of people expected for the festival tomorrow.

Plaza de La Revolución

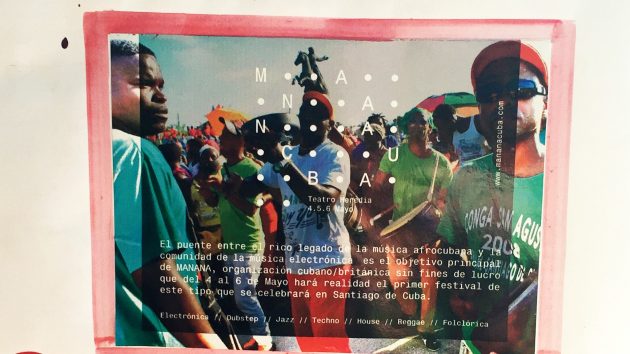

Hand-drawn sign for MANANA CUBA

Hand-drawn sign for MANANA CUBA (detail)

As I return to the veranda I notice the people assembled for the opening speech moving inside the Teatro Heredia. so I follow the crowd inside where I hear the distinctive sound of Batá drums and bells. Given the revered place that Yoruban percussion and singing has in Cuban cultural and spiritual life, it’s not surprising that the ceremonial opening of the Manana festival begins with a group of Batá drummers called the Santiago Batá Ensemble:

After the performance, I speak with a member of the group, a man named Silvio Bell Echevarría, about the significance of this opening performance and of the Batá drums that already seem to be everywhere at Manana. I’ve been pondering about this, not only for my research but as a fellow percussionist. Silvio’s face perks up with a warm smile and a rich baritone voice belying years of musical experience. He tells me about how and where different types of ceremonial (Fundamento) vs. secular (Aberikula) Batá drums can be played and with which rhythms. It’s all a bit much to remember amidst the constant stimulation of new visual and aural information I’ve been taking in since I arrived in Cuba, so after we finish our rum and cokes, I ask him if he’d be interested in doing an interview the next day. He accepts my request and we agree to meet up the next day for a few performances and a late-afternoon interview on camera.

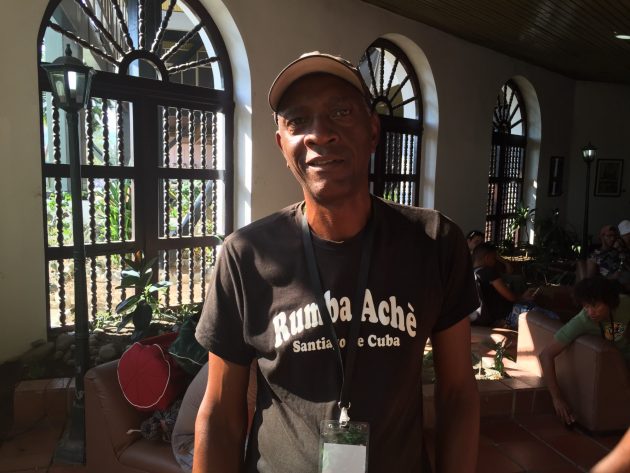

Silvio Bell Echevarría

As the week continues, Silvio and I will fall into a sort of barter-based, professional friendship, spending hours together each day, during which he will educate me about the different types of Afro-Cuban rhythms and song forms presented at the festival, as well as the differences between music of the Oriente (East, i.e. Santiago) and the Occidente (West, i.e. Havana/Matanzas) of Cuba. He will describe styles such as Tumba Francesa (Santiaguero music societies with Franco-Hatian origins), Guaguancó, Changüí, Son Montuno, Son Cubano, Gagá, Vodún, Rumba, Son, Merengue Haitiano, and expound on the differences and overlaps between music of various Afro-Cuban religious sects from Ifá to Palo.

By the week’s end, I will have bought a couple of CDs from Silvio, T-shirts, and many drinks for us both. In return, he supplies me with a wealth of insight into Afro-Cuban music and its cultural and spiritual roots. Our conversations last for hours and Silvio never seems to tire of my questions.

From my end, it’s more than a fair deal.

That night, after taking in a spectacular sunset at Balcón de Velasquez…

Sunset at Balcón De Veláquez amidst Zika virus fumigation

I make my way to Casa Micaela, formerly Casa de la Música, expecting another performance, but the place is still empty and the band is still rehearsing. Gradually, the place fills with a mix of foreigners and Santiagueros. This show is not officially part of the Manana Festival programming but many of the artists performing — DJ Jigüe & Guampara Productions crew, Wichy De Vedado, Nickodemus, Uproot Andy — are on the festival schedule. It seems word of the off-site performance has gotten out because I see professional video cameras start to set up and it’s not long before the press presence begins to dominate the space, with cameramen edging onto the stage to get their close-up shots.

Despite the large film crew presence onstage in such a tight space, the artists eventually get comfortable enough to dance and perform while navigating around the half dozen active camera operators, and deliver an electric performance nearly until dawn.

While a I wait for a moto-taxi at the plaza to take me home for the night, a staggering drunk man sings boldly into the night to an audience of none, though with an incredible voice that makes me think this man should be a star.

“One day I’m going to become a millionaire from my music,” he tells me when he passes me by.

Then, “Can I have 3 CUCs so I can get some more rum?

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.