Roger Glenn: A lifelong Latin heart

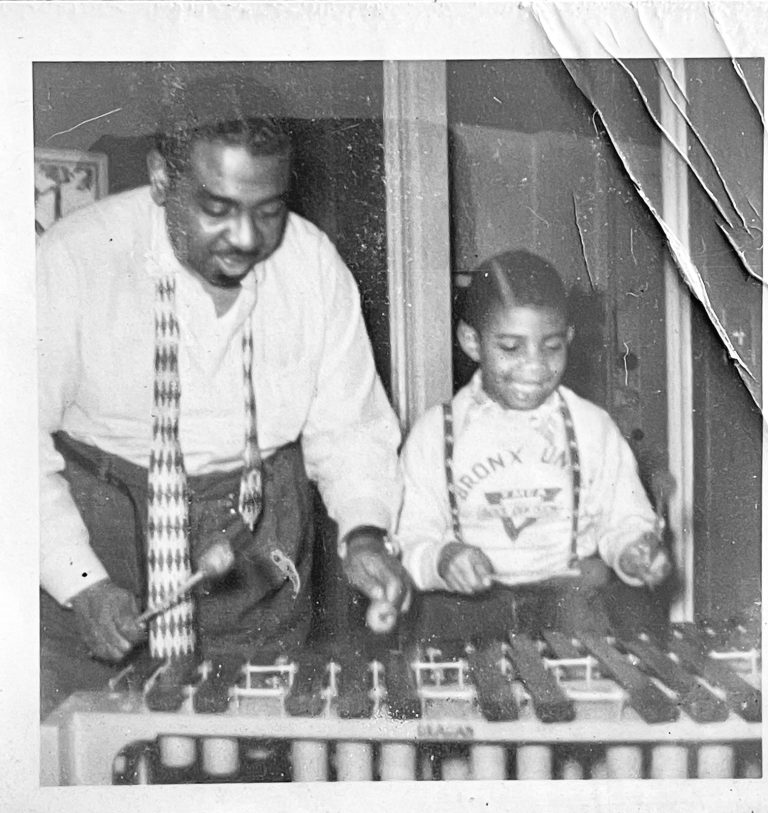

23 December, 2025The photograph shows the hero of this tale, Roger Glenn, sometime in the late 1940s when he was five or six, learning to play the marimba with his father, Tyree. An alumnus of the Swing Era, Tyree Glenn played trombone with Cab Calloway during the orchestra’s “Hi-De-Ho” prime between 1939 and 1946 and with the small-group-within-a-group, the Cab Jivers. He was even implicated in the notorious “spitball” incident that led to a young disruptive Dizzy Gillespie getting his marching orders. Was it Gillespie or was it Glenn? In any case, Glenn senior went on to play trombone and vibes with Duke Ellington before quitting life on the road to be a staff musician for CBS for radio and TV work in the New York area, then latterly securing a slot with Louis Armstrong’s All Stars. Being present during Roger’s childhood meant that he was able to pass on his musical talent to both his sons.

I spoke to Roger on Zoom, ensconced in his sitting room with his wife Beth in their home in Pacifica (“a pretty cool place,” as the strapline goes) with a view across San Francisco Bay. We chatted initially about some of his childhood memories. “I remember going to a rehearsal with my father with Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn [the Duke’s regular co-composer] was there,” Roger reminisced. “And for that famous Great Day in Harlem photo [an iconic photo from 1958 of many of the New York jazz giants of the time arranged on the front stoop of a Harlem brownstone], my father asked me if I wanted to go with him, but I said ‘no, those are your friends.’ I never really thought that one day I’d be playing with some of them. The first artist I ever recorded with was [pianist and composer] Mary Lou Williams. That was 1969. Before that, I played in the army band with Grover Washington and Billy Cobham. That was ’66 to ’69.”

In view of his upbringing, I asked him whether the jazz life was therefore inevitable. “Well no, because I wanted to be a commercial pilot. But little did I know about how limited the opportunities were for black airmen at that time… In New York, you were exposed to a lot of different music. There was the Latin craze that was happening, the Mambo era of the 1950s. You went to the Palladium and places like that and Tito Puente would be playing, and downstairs at the Village Gate every Monday night “Symphony” Sid, the radio DJ, ran the Latin thing. So I was into jazz and Latin music, and my brother, who plays sax – he lives in Germany now – he was into jazz and R&B stuff. My mother liked Latin music, too, so that was my education growing up: a combination of jazz, Latin music and R&B. When I was coming home from school one day, I came across this record in the gutter, the label was washed off by the rain, and I took it home and discovered that it was Cachao’s Descargas. Later on, I recorded with him and Mongo Santamaria on Mongo’s Way. He brought in some great Cuban musicians for it, Cachao and others. It would have been 1971, ’72.

“When my brother was playing with his R&B band up in the Catskills one summer, he got a job for me working the spotlight for the shows in the evenings. So I’d listen to my brother playing and in the afternoons, there was a group by the hotel pool called La Plata Sextet. And that’s where I learned to dance [laughs]! And I’d sit in on flute and I learned to do the cha-cha, the mambo, the merengue. That was the environment.”

Roger plays more than 18 instruments, so I asked him about his musical foundation. “In fourth or fifth grade, they had like an instrument audition and they asked me what I’d like to play, so I said I’d like to play the flute because Herbie Mann and Johnny Pacheco and all was happening. But the guy leaned over to me and said, ‘We’ve got enough flute players, go over there by the clarinet section.’ So I started playing clarinet formally, and later on my father bought me a flute. But… the very first instrument for me was playing the vibraphone. Or rather, the marimba.” At which point, he dug out our cover photo. “He used to put them [the vibes] next to the crib, so they were always there.” Did he have a favourite instrument, I wondered? “Hopefully the one I’m playing at that time [chuckles]. It’s like the songs I compose: you know, this feels like an alto sax; this is a tenor sax; this is more a flute thing or a vibe thing. That’s how I go about it.”

Our conversation moved on to the subject of Roger’s appearance on Donald Byrd’s seminal Black Byrd for Blue Note in 1975. The interplay of Roger’s flute and the leader’s trumpet defines the sound of a masterpiece of jazz-funk – with pronounced rhythmic Latin influences. “That’s the Englewood connection [to where Roger moved in 1954]. Donald Byrd used to come to Englewood, New Jersey. Also, I grew up with Fonce and Larry Mizell [the album’s producers/arrangers and composers], and Larry called me up – I was living in San Francisco by then – because Donald wanted to do an album that was totally different to what he’d been doing, and so the idea of adding me on flute came up. So we put the album together down in LA and it became a big hit. At first there were no names on the album [sleeve], just Donald Byrd, and a lot of great musicians were on it, like Harvey Mason on drums and even Bobby Hutcherson [on vibes]. But no names! My mother heard this DJ playing it on the radio and he didn’t know who the flute player was on this great album, so she called the station and said ‘My name’s Gloria Glenn and my son’s name is Roger Glenn and it’s him playing flute,’ and the guy said, ‘Oh you’re lying!’ [laughs heartily]. It was crazy. But our names finally appeared on this album.

“So, with this hit going on, Larry was approached by Fantasy [Records] and asked if he knew of any artists to produce. My name was mentioned, so we went into the studio [to record 1976’s Reachin’] but it was really complicated by the fact that Larry wasn’t there much of the time. I put this band together and we were practising, but it was just very difficult. I guess the politics of the deal that Larry had made with them [Fantasy], it just didn’t work out. Larry was working with this other band down in LA and there was all this stuff going on and we just weren’t getting the attention that we needed. It was all just really ugly, and I guess that’s one reason why I never did any recording of my own [afterwards]. That’s showbiz!”

Our chat then shifted to the thriving Latin scene in the Bay Area. “Yes, for years I worked with this guy Cesar Ascarrunz, who had a club called Cesar’s Latin Palace. The first time I played there was on tour with Mongo Santamaria. Later on, I stopped by the club with the singer and the drummer in the band that my brother had, Tyree Glenn & The Fabulous Imperials, who lived in the area, and he offered us a job and that’s how I came to stay here in San Francisco. All these Latin musicians would come by the club: Tito Puente played there. Tito and I go back to New York; I used to do commercials with Tito and Charlie Palmieri.”

I love the fact that Roger played flute with vibraphonist Cal Tjader, vibes with flautist Herbie Mann, and both with Dizzy Gillespie. How did this come about? “When I was stationed on Hawaii, I was really thinking of re-enlisting [at the end of his original contracted tour of duty], but I was on leave and I went home to Englewood, and Dizzy lived in Englewood. One day, I was hanging out at his house and he asked me about my plans and I told him I was thinking of staying in the army and transferring to fly helicopters and stuff like that. And he said, ‘Well, if you get out of the army, then you can work with me.’ So I went back and I told the commander, ‘I’m not going to be re-enlisting because I’m going to be working with Dizzy Gillespie.’ [Laughs] I got out in 1969 and I didn’t work with Dizzy till 1978-79. We recorded around that time and we did some gigs when I was back east, and later I got this call from him saying we’re going down to South America, would I like to join him? So I said great! We went down there around ’79, and I love Brazilian music. We went through Brazil, Argentina and so on. When the gig was over, I stayed on in São Paulo and Rio, just hanging out.”

And Cal Tjader? “I used to see him in New York when he was playing at the Apollo. He had [conguero] Armando Peraza playing with him, and I introduced myself. Later, we worked together with Dizzy; we did the Monterrey Jazz Festival. Then one day I’m walking down Market Street in San Francisco, and I see that Cal’s playing at this club, so I dropped by and I had my flute with me and I sat in on the last song of the evening. He said, ‘You know, we’re going into the studio tomorrow, would you like to join us?’ Great! So I joined them in the studio, no rehearsals or anything like that, and we put together this album, La Onda Va Bien [1979], and it won a Grammy.”

And so finally to Roger’s second solo album, almost 50 years after Reachin’, My Latin Heart. It was actually intended for release a few years earlier, but a number of factors – including the pandemic and a temporary suspension of the Grammy category at which it was potentially aimed – conspired to delay it. When it was released, My Latin Heart failed to make the time limit for consideration for the Grammys – although the video for a key track, “Congo Square”, was up for consideration (but didn’t make the final cut). Roger talked about the track in response to my suggestion that it is perhaps the album’s quintessential number. “Music is about cultures coming together. Congo Square is in New Orleans, and New Orleans in terms of how jazz was formed, it’s a combination of [so many diverse] European and African influences…. Different dynamics, different cultures… You have to study these things to realise the different interactions between all these different cultures. You listen to it [‘Congo Square’] and it starts off with a European classical feel and then there’s 6/8 rhythm, .the African feel, and then they come together… I wanted to take it even a step further: on a bigger live performance I would add rap, as part of that whole cycle of things that have developed through generations… So there’s all that, and also I love to dance [laughs]. The music inspires me.”

Despite the circumstances that conspired to make My Latin Heart a difficult birth, had its reception been as positive as he had hoped, I wondered? “I just got an article from a critic in Russia,” he revealed. “It has been looked at and appreciated in Turkey, France, England, South America, all over the United States, Australia, all over this planet. I’m happy in that respect. But the business side of trying to get gigs, that’s a whole other story. Being a musician, my father used to say ‘it’s the dirtiest business in the world’ [laughs]. There’s a lot of stuff involved. I mean, we live in an age now… I call them [CDs] my calling cards. Here I am, take a listen to this sometime. But you’re not making any money off the CDs; the music’s on YouTube and the Spotifys of the world. But even touring is limited; if you can get into a festival or something like that, there are all these factors: getting there on your own dollar, staying there on your own dollar, all of those things. And playing locally, I mean people say ‘Yeah, I heard it the other day’. It wasn’t like when I worked at Cesar’s. Every week we were playing, but that was more for dancers – they were more interested in dancing than they were in really seriously listening to the music.”

Hopefully he has some plans for a follow-up. “Oh yes. That’s what I do, you know. I couldn’t make it as a pilot at the time I wanted to be a pilot, so music is what I do.” Roger Glenn has been doing it for a long, long time and let’s hope that this youthful octogenarian multi-instrumentalist will be doing it for a lot longer still.

For more on Roger, visit https://www.rogerglennjazz.com/. Or, to follow him, check out https://www.facebook.com/RogerGlennJazz and https://www.instagram.com/rogerglennjazz/

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.