From Queen of Socialites to Outsider: ‘The Good Girls’ is the Flipside of Alfonso Cuarón’s ‘Roma’

02 September, 2020The screen remains blank during the opening voiceover of Las niñas bien (2018, dir. Alejandra Márquez), while the protagonist, Sofia (Ilse Salas), muses over her birthday party preparations:

“Silverware, Grand Marnier glasses, white wine glasses, I don’t know about those calla lilies, change them for tulips. I ask Mari to hit the octopus sixty times, otherwise it’s chewy and that is sad.”

While this is a rare insight into the protagonist’s thoughts – the rest of the film will rely mostly on silent close-ups to reveal her inner thinking – it foreshadows the character’s vapid preoccupations throughout the rest of the film. Buying dresses in New York, playing tennis matches, lunching at an exclusive club and organising much vaunted parties for other socialites appear to be the protagonist’s quotidian activities.

Whilst portraying the sumptuous lives of the Mexican upper-classes might appear to have satirical undertones – the Financial Times deemed this film to be an “acid social satire” – director Alejandra Márquez (Semana Santa) eschews the comedic path in favour of non-judgmental realism. As she declared in an interview with Gatopardo, she did not wish to create yet another satire criticizing the Mexican elite. This fine balance is struck elegantly: like Joanna Hogg’s Archipielago (2010), the film captures the scandalous views of its snobbish characters without letting that overshadow their own very human miseries. In depicting the fall from grace of a wealthy family during a financial crisis some viewers might even feel an inch of sympathy for these rather dislikeable characters.

Based on the eponymous book written by Guadalupe Loaeza in 1987, Las niñas bien is the flipside of Alfonso Cuarón’s Oscar-winning film Roma (2018). Focusing on a detailed portrayal of a housekeeper working for an affluent family, Cuarón’s protagonist may have well taken orders from a character like Sofía. Despite their differences, the films’ themes do overlap: Cuarón’s story was inspired by the housekeeper who looked after him while he was growing up, and Márquez’s film shows how the family’s children spend more time with the house staff than with their parents. The only piece of advice Sofía is heard giving her children is ahead of them travelling abroad for a camping holiday: “Remember not to hang out with Mexicans, OK?” Akin to how she only buys dresses abroad, she wishes her children to make only foreign friends. In a fleeting moment of self-awareness (which tellingly occurs when she is drunk), Sofía asks the elderly housekeeper, Toñis: “Am I as bad a mother as my mum?” By implying that Toñis knows about Sofía’s childhood, it is suggested that she looked after her as a child. Toñis’ plight as a life-long housekeeper over different generations in the same family points to the lack of social mobility among Mexico’s working class. This is precisely what Cuarón focuses on in Roma, as Lila Avilés also does in The Chambermaid (2018), a masterful take on the life of a Mexican hotel chambermaid.

While the film does not explore in depth the socio-political context underpinning the family’s changing fortunes, the script offers enough snippets of information to locate the action during José López Portillo’s tumultuous administration (1976 – 1982), following the maelstrom caused by the 1982 financial crisis which saw a devaluation of the Mexican peso against the US dollar. The hubris of Sofía’s husband, Fernando (Flavio Medina) is pointedly captured in the film’s opening scene: the birthday party. Right after a guest introduces the plot’s political context by telling a joke about the “saca-dólares” (people taking their savings in dollars out of the country), Fernando arrives with his birthday present: a brand-new car for his wife. Oblivious that the impending economic crisis will also hit the elites, he indulges in an ostentatious expense he will soon regret.

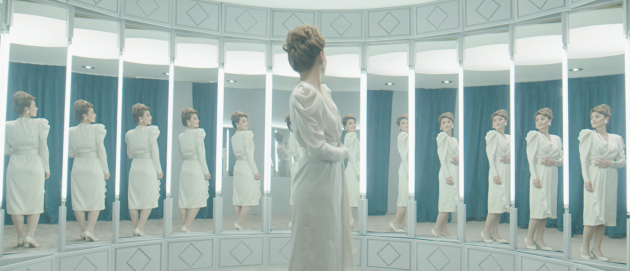

Sofía’s fall from grace – from wealthy queen of the socialites to outsider – will be marked by some hackneyed narrative devices, such as the credit card which gets rejected at the store, or the child who asks, “Mummy, are we poor?” Márquez is at her best when depicting Sofía’s painful social descent by showing rather than telling. Halfway through, the protagonist’s immaculate skin is marked by a rash which will only worsen, manifesting her inner stress. Accepting her new ordinary self, Sofía lifts a (rather literal) weight off her shoulders when she bins the shoulder pads that had been worn under every outfit.

Throughout the film Sofía’s social deracination is juxtaposed with the ascendancy of the gated community’s newest resident, Ana Paula (Paulina Gaitán). Initially shunned by the protagonist for being “tacky”, Ana Paula climbs the social ladder as her husband’s finances appear to strengthen rather than diminish during the crisis. In my favourite scene, towards the end of the film, Sofía attends the birthday party Ana Paula organised for her children. The fragmentary nature of the sequence, presented as a non-chronological montage of isolated moments at the party, reflects Sofía’s internal disarray, which is exacerbated by Tomás Barreiro’s unnerving soundtrack. Her old circle of friends barely speaks to her after her husband’s economic debacle, so she spends most of the day smoking on her own. The theme of the party, ‘Cowboys and Indians’, is an apt one as the background of a scene which shows the powerful become powerless, a vicious circle involving oppressors and oppressed which has characterised Mexican history since colonisation, as Carlos Fuentes depicted in The Death of Artemio Cruz (1962). In this way, Sofía’s demise coincides with Ana Paula’s ascension. When the party’s host attempts to be kind and offers to buy her purse (an indirect way of helping her financially), Sofía refuses and displays her most supercilious self. Instead, she takes some gold cufflinks belonging to Ana Paula’s husband. Illustrating her enduring haughtiness, the protagonist appears more willing to steal than to accept help. In the scene’s closing shot Sofía’s characteristic sangfroid gives way to a dishevelled outburst: she helps her daughter accumulate sweets during the piñata by stealing from other children. In doing so, she reveals herself in public as a spoilt child.

As often is the case, the English title of the film fails to capture the full sense of the original one. In Spanish, being described as ‘bien’ can mean both good and well-to-do. The nature of Márquez’s characters typify the fallacious nature of the term’s double usage as these two characteristics rarely go hand in hand in the film.

The Good Girls is available to stream on MUBI.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.