Mario Vargas Llosa and the relationship between politics and journalism

10 September, 2010Mario Vargas Llosa’s statement “literature is fire” provides both an insight into his views regarding the potent weight he feels literature may carry and also the effect that words can exert over him and, although the Peruvian writer’s political beliefs have shifted to the beat of Churchill’s epigram since he was the youngest of the big four comprising Latin America’s boom period, his love of writing has never wavered.

Growing up in a state of restricted civil liberties and a student under the corrupt tyrant Manuel A. Odria at a time when all student activities were observed on, the regime unsurprisingly rendered Llosa’s character to be extremely politically oriented from an early age. Additionally, while the boom period in South American literature’s most significant contribution to contemporary literature may be magical realism, Llosa’s work has consistently featured a strident realism and critique of political extremity that resulted in 1000 copies of his first work, The Time of the Hero, being burnt by Peruvian generals who thought it the work of a depraved mind on the bank roll of sadistic Ecuadorians. Like much of Llosa’s work, the structure and use of shifting narratives challenged what the novel was capable of delivering and while Llosa aligned himself to the left, supporting the ascendancy of Castro’s Cuba at the time, many critics believe his novels lost some of their magic once his disillusionment with Castro’s increasingly authoritarian stance and tendency to banish homosexuals from the country in order to “cure” them, resulted ultimately in his abandonment of socialism.

It is the 1960s then that many consider to be Llosa’s best period, when he was simultaneously at its most politically critical and, as some critics assert, of less obvious entertainment value than more recent works such as The Bad Girl – a reworking of Flaubert’s A Sentimental Education. Llosa is quick to disparage those who present his canon since the 80s as being more flippant in tone and although he acknowledges his narrative has shifted often, he doubts he has ever ceased to produce work of contemporary value or that literature need deal with in order to present relevant commentary on the human character or its politics. Llosa like Salman Rushdie, believes the writer has a social obligation to name the unnameable, to start arguments, take sides and stop the world from going to sleep. Society will always need writers and especially writers prepared to offer commentary on political regimes, of which Latin America has too often served as stage for the past 100 years.

It is perhaps unsurprising then that Llosa, as well as his literary accolades, has a formidable and varied canon of journalism. This carries with it numerous challenges. Chief amongst these is his fear it will become entertainment, merely to allow its writers to survive, a comment suggesting he has little faith in the populace’s current ability to take the time to digest worthwhile but lengthy works when temporary diversions exist. The objective of journalism Llosa asserts, is to provide true information to a country, a value with which he generally also treats his novels, while also recognising the main difference between novels and journalism is “that journalism is limited by the real world”. While that may be the case, his realistic treatment of the world in the majority of his work may reflect his feeling that he is best able to comment meaningfully on the world and Peru in particular via this channel.

There is always going to be a dichotomy of interest between the arts (in this case writing) and political activity. Llosa himself recognises there is an incompatibility between writing and political activity with his book A Fish in the Water, acting as a perfect example. The book, half of which details his presidential attempts, was better received than many of his policies during the time of his presidential campaign. Although a political character and former activist he is however primarily a writer and this need be recognised before criticism, lest it should be rendered obsolete. Countries need politicians that have no interests separate from politics, though whether it wants them is quite separate and liable to be dictated by the state of the economy and current statistics from Peru report half its population live in poverty.

Similarly, while struggle often is political, pleasure is not and since being recognised as a writer of great significance in the 60s his appointments and invitations to various educational faculties were invariably as a writer and granted a freedom and style of living assuredly alien to the majority of Peruvians. Affluence of any kind affords one an indulgence in politics as opposed to an essential need for a system to improve because otherwise a countries citizens die and this was perhaps never clearer than in his campaign for Presidency with the rightwing coalition FREDMO in 1990 whose failure can be partly attributed to proposed tax increases on the poor, partly to Llosa’s reluctance as candidate (he frequently stated during the campaign to be running from a sense of obligation rather than desire) and a political naivety.

Since relinquishing any participatory function in politics, he has made it clear that he has little confidence in the ability of the human character to resist the “monstrous effects” he believes politics exerts on people regardless of the goodness of their ideologies, which in turn extends to his belief that all democracies are exceedingly fragile since they are mirrors of the human character. Llosa now spends approximately 3 months a year in Peru; a decision which merits criticism from those who regard it as a political betrayal and the rest of the time between London and Spain where he has properties. Living where he chooses however is his prerogative as a successful, and now old, man who would possibly argue that revolutions are a youthful occupation and as a young and middle aged man were indeed his to a degree. The political criticism of Llosa is one that has become increasingly prevalent in Peru since the 1990s and what is viewed as, despite his contra wise assertions, a slide further right in politics. He has long since made claims to be a politician and intends only to live wherever he writes best, the price he seems happy to accept for this freedom of abode being that any critique he directs at Peru is deemed void.

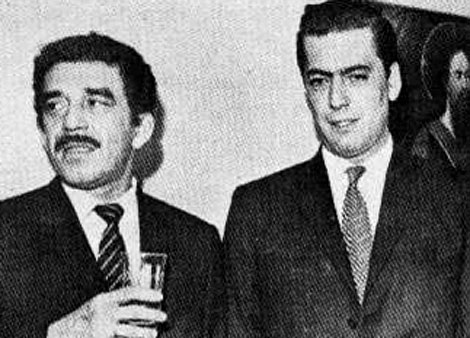

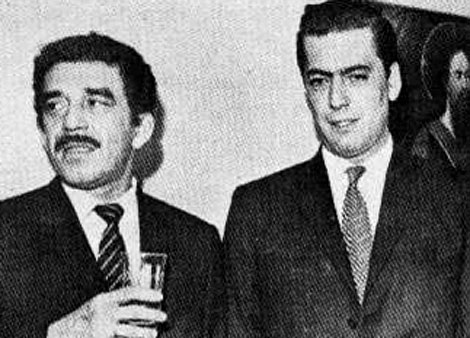

Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Mario Vargas Llosa:

Due to their involvement in the boom period, Llosa often shares the honour of gracing the same sentence as Gabriel Garcia Marquez and also shared a friendship with him, until Llosa ended it, pre-empting Florence and the Machine by 30 years by punching Marquez in the face at a film premiere in Mexico City in 1976 for reasons which have subsequently never been rendered public, though political variance and women have been cited. Despite never having rekindled their friendship in 2007, to celebrate the 40 year anniversary of Marquez’s Nobel prize winning novel 100 Years of Solitude, it was rumoured that the republication of the novel would be preceded by a laudatory foreword authored by Llosa. This was subsequently revealed to be, in fact, an excerpt plucked from an essay Llosa had written in 1967, prior to the estrangement (the republication of which he had suppressed) and which leaves any inclination to proffer an olive branch still on the table. The colossal reputations of both writers makes the perpetuating spat one of modern literatures most significant feuds, sharing the mantle with Salman Rushdie abuse-laden relationship with John Le Carre.

While Llosa has ink he will continue to write and unless you are so politically sensitive as to be disgusted by the photo of Margaret Thatcher in his London home, he will be read.

Recommended Reading:

The Time of the Hero (1963) – Buy at Amazon

La Casa Verde (1966) – Buy at Amazon

Conversation in the Cathedral (1969) – Buy at Amazon

Death in the Andes (1993) – Buy at Amazon

A Fish in the Water (1993)

The Feast of the Goat (2000) – Buy at Amazon

Buy Mario Vargas Llosa at Amazon

Interview with Maria Vargas Llosa by David Frost:

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.