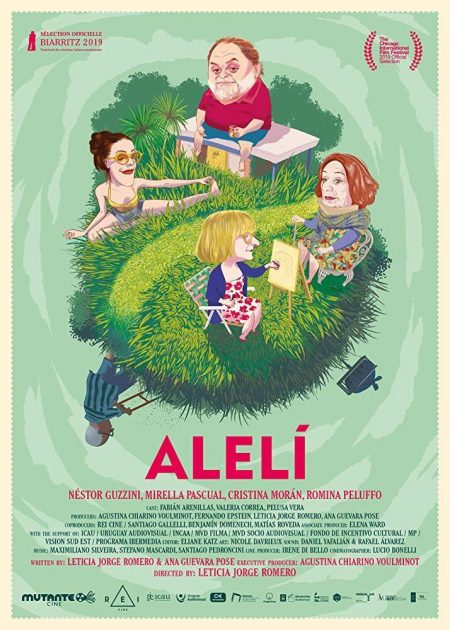

‘Alelí’: A Father’s Death Sends His Heirs into a Downward Spiral in this Uruguayan Comedy

01 March, 2021In the opening scene of Alelí (2019, dir. Leticia Jorge) a notary reads out loud the details of a sales agreement. A beach house in an indeterminate location is being sold for U$S 134,000 plus one unit in the housing complex which will be built thereafter. A rather uncomfortable and tense aura envelops the family who is selling the property, which the wily buyer attempts to diffuse in vain. 50% of the amount will go the oldest character in the room, Alba (Cristina Morán, a Uruguayan national treasure making her cinematic debut at the age of 90). The rest is split among Alba’s three children, as each of the remaining present characters, Ernesto (Néstor Guzzini) and Lilián (Mirella Pascual), will receive 16.66% of the sale. The maths only add up when the third and youngest member of the family, Silvana (Romina Peluffo), comes into the meeting halfway through. A sudden blackout forces the sale to be postponed, as the notary cannot print out the contract. The electrical short circuit reflects the charged clashes within the family which will define the film: Silvana’s immaturity, Ernesto’s mercurial temperament and Lilian’s self-interest are all palpable within the first scene, while Alba seems to have lost the willpower to mediate between her three adult children after her husband’s death.

The opening scene introduces the question which will remain latent throughout: will the family actually sell the house? Built by the deceased patriarch, the house, named Alelí after each of the characters’ initials, might be the last threadbare bond holding the mourning family together. If any viewers feel that the stage is set for a Succession-style backstabbing inheritance drama, they will be sorely disappointed. This hybrid film – part comedy, part drama, part costumbrista portrayal – is a candid and warm exploration of loss, mourning and family dynamics.

After her acclaimed directorial debut with Tanta agua (2013, co-directed with Ana Guevara), Leticia Jorge’s first solo film, Alelí, became Uruguay’s submission for the 2021 Academy Awards. Like so many recent Uruguayan films (El viaje hacia el mar, Mr. Kaplan, Rincón de Darwin, El campeón del mundo), Tanta agua and Alelí also have a penchant for eschewing the country’s capital and epicentre (where half of the country’s population live) as setting. Instead, Jorge’s films depict Uruguay beyond Montevideo, and use journeys as a central device within their narratives. In both films physical traveling mirrors an attempt to travel in time, to a prelapsarian past where family dynamics were less thorny.

Another aspect which these two films share is the stellar presence of Néstor Guzzini in a central role. Without wishing to suggest that the characters he plays in both films are the same, Guzzini’s performance captures something idiosyncratic about middle-age masculinity crises among Uruguayan men. His characters seem unable to adapt to the shifting reality around them, and with Quixotesque obstinacy keep running into the same windmills. These men become heads of family but appear ill-equipped for the role. This mismatch between expectations and reality, though, is imbued with tenderness. And the warmth which defines the film manages to avoid taking the tempting turn towards mawkish avenue.

The symbolic playfulness of the film also amplifies its structural tensions. Ernesto and Lilián have a minor car crash at the start, foreshadowing the clashes between these siblings which will drive the narrative. Silvana’s initial is not part of ‘Alelí’ because “she was born late”, an apt origin story for a character whose defining feature is tardiness. Lilián’s ‘I know best’ attitude may be fuelled by the fact that, as the mis-en-scene signals, she is a teacher. When the cake decorated with the face of the dead father is cut into slices, Ernesto gets his dad’s eye, a suitable metaphor for a character who feels constantly watched by his father.

Having left my native Uruguay for Britain a long time ago (and been a devotee of the British sense of humour for even longer), I have often been dismissive of Uruguayan on-screen comedy: too slapstick, too dependent on lewd puns, frequently punching down and scared of self-deprecation. Perhaps it is nostalgia for my home-country in the covid age, but this film has made me reconsider my views. It brilliantly uses humour to capture the passive aggressiveness within the family, creating an agonising discomfiture which keeps viewers gripped to their screens. Ernesto’s deadpan one-liners can only be followed by awkward silences. But the film also knows when the plot demands something more extravagant: seeing a middle-age, inebriated, podgy man who is wearing just a towel resisting arrest being a case in point.

What happens when the rift between family members is so deep you cannot have Sunday lunch without bitter arguments? What unfolds when the few things keeping you connected – your parents, your beach house – start fading away? It would be lazy to call this family ‘dysfunctional.’ If it can be called this, it is only to the extent that every family navigates these same turbulent waters. Leticia Jorge’s film is a poignant reminder of this.

Alelí is available on Netflix in some countries, and it can be rented from Mowies.com.

Click here to read an overview of the Latin American contenders for the 2021 Academy Awards (Alelí was Uruguay’s submission).

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.