“Language is the Crucible of Power”: An Interview with Carolina de Robertis

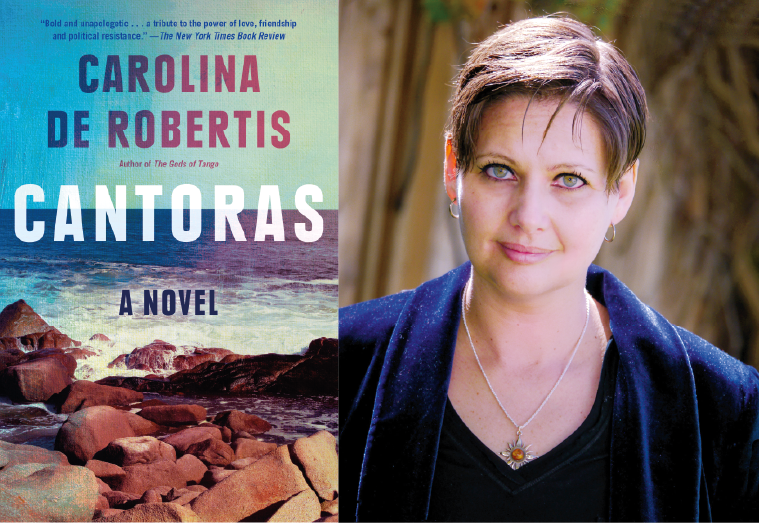

03 February, 2021Carolina de Robertis was a winner of the Stonewall Book Award, the Reading Women Award, a Lambda Literary Award and was a Kirkus Prize finalist for her novel Cantoras. She has translated Latin American and Spanish literature into English, and is an editor of the anthology Radical Hope: Letters of Love and Dissent in Dangerous Times. Her own novels include: The Gods of Tango (which also won a Stonewall Book Award); Perla; international bestseller The Invisible Mountain and The President and the Frog (forthcoming in May 2021). She lives in Oakland, California.

Sounds and Colours spoke to Carolina about Cantoras and her literary work. Set in Carolina’s native Uruguay, Cantoras tells the story of five lesbians through the dictatorship years of the 1970s and 80s, inspired by real women who set up a community in the coastal town of Cabo Polonio.

How well known is the story of Cabo Polonio in Uruguay?

The popularity of Cabo Polonio has exploded since I first visited, twenty years ago now, on the trip where I first met the women whose lives inspired this novel. It’s become a sought-after beach paradise, with tourists from Brazil and Argentina flocking to the famed bohemian enclave and stunning shoreline. But even so, the full story of this place – how it served as a refuge for queer people in the dictatorship years – seems to still fly under the radar. It’s under-documented, as queer histories often are.

It feels like the five women in Cantoras have a ‘shared language’. They use euphemisms, like describing visiting their clandestine beach as “going to church”; they adapt masculine words into feminine ones; and they comment on words with dual meanings. Could you comment on this shared language in the book?

Thank you for this insightful question! It’s true: the characters in this book play with language, stretching it in new ways, playing with it, bending it to fit their evolving realities. Queer communities have done this throughout time. When your reality can’t be fully spoken, when the very language you speak is coded against your existence, linguistic play can be a site of resistance. And of innovation. Beautiful innovation = a beautiful queering.

I noticed that the novel contains several conversations where characters discuss language itself, such as the meaning of words and phrases, for example discussing the meaning of the word ‘esposas’, or the use of the term ‘transfer of power’ to describe a coup. Is this commentary on language choices something you particularly wanted to include in Cantoras?

I think I just can’t help myself! Language is a crucible of power. It can reveal; it can erase. It can oppress; it can liberate. “We do language,” Toni Morrison said in her Nobel acceptance speech. “That may be the meaning of our lives.”

Continuing on the theme of language, a significant word with multiple meanings is the titular ‘cantoras’. Why did you choose ‘Cantoras’ for the title of the book?

Most of my novels have gone through a long litany of titles before settling on a final one. This book is no different! The title Cantoras came at the very end. And yet, now, it feels like the truest title possible: this word a group of lesbians, queer women, used to refer to women like them in a time of intense repression.

The word ‘cantoras’ means, ‘women who sing.’ The term can have racy undertones, as in, does she sing? Would she let me make her sing? Wink, wink. But it also holds other burning questions: What kind of music can a queer woman make of her life? And at what cost? In a world that wants you silent, what does it mean to own your voice? As a reader as well as a writer, I look to novels for this – for the exploration of burning questions.

When translating this book into Spanish, could you say a bit about your decision to leave some Spanish words untranslated in the English?

When I originally wrote the book, in English, I included words in Spanish because they’re part of the characters’ inner ecosystem, part of how they would hear their own thoughts. My early drafts often have a lot more Spanish in them, especially in dialogue, and especially as inflected with regional Rioplatense Spanish colloquialisms. Then, later on, I weigh each word for what it’s doing in the text, and for which rendering might best serve what I’m hoping to portray.

The dictatorship in Uruguay is referred to euphemistically as ‘El Proceso’ in Cantoras, and we can see that the characters express some of their emotions towards the regime using this term. I’m curious to know, is the term ‘El Proceso’ still used to refer to the dictatorship today? Does it have the same connotations that it used to have?

That’s an intriguing question. No, the term El Proceso doesn’t loom now the way it did back then, because it was the preferred term of the regime. I’m glad to say that Uruguayan society has resoundingly rejected the horrors of the dictatorship years, and universally decries the violations of human rights, in far more direct terms. Fifteen years of progressive third-party leadership have changed the tone entirely.

I’m deeply inspired about Uruguay’s trajectory after an era of political catastrophe, and I believe that we in the US could stand to learn from that history, given where we are; as it happens, I explore those themes among others in my next novel, The President and the Frog.

You wrote Cantoras in English and then translated your own text into Spanish. How did you find the act of translating your own novel? I have also read, and really enjoyed your English translation of Laura Restrepo’s novel The Divine Boys, was anything easier or harder translating your own work compared to translating somebody else’s?

Thank you for reading The Divine Boys! I’ve been a huge fan of Laura Restrepo’s work for years, so it was a joy and privilege for me to translate that fiercely feminist novel.

I’d say one difference in translating my own work, rather than that of another writer, is that I can immediately access the original author’s underlying intent, which is often key to a translator’s more complex decisions. As for what it was like to translate my own novel into Spanish: as an immigrant writing about my nation of origin, it was a breathtaking experience, a long and intricate bridge leading me home.

Cantoras is published by Vintage and can be purchased at Blackwells (UK) and Barnes and Noble (US). Click here to read Carolina de Robertis’ account of translating her own novel into Spanish.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.