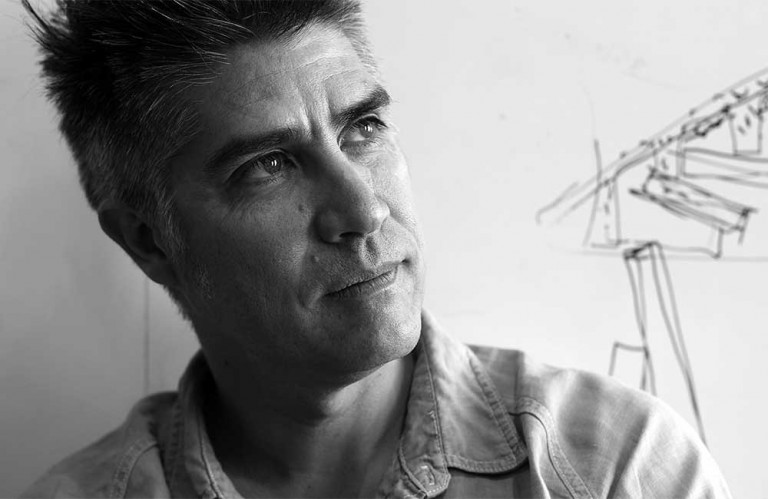

Alejandro Aravena Awarded the 2016 Pritzker Architecture Prize

04 April, 2016Alejandro Aravena, the radical Chilean architect who pioneered a new wave of social housing and urban reconstruction in South America, has been named this year’s winner of the Pritzker Prize. Aravena will receive the award at a ceremony held at the United Nations Head Quarters in New York on April 4th, where he will become the first Chilean architect, and the fourth Latin American, to receive the prize.

When founders Jay and Cindy Pritzker awarded the first Pritzker Prize in 1979, they did so with the belief that “a meaningful prize would inspire greater creativity within the architectural profession”. Since 1979, the prestigious annual award has gained an international reputation and is often referred to as the “Nobel Prize for Architecture”.

The Pritzker Jury’s decision to honour Avarena was based on a dual application of his practice and ideology. John Pritzker, son of the prize’s founders, stated that Aravena’s work not only produces stiking buildings, but also addresses key challenges of the twenty-first century. “His built work gives economic opportunity to the less privileged, mitigates the effects of natural disasters, reduces energy consumption, and provides welcoming public space,” noted Pritzker at the official announcement in January. “Innovative and inspiring, Aravena shows how architecture at its best can improve people’s lives” he continued.

Quinta Monroy (elementalchile.cl)

The architect himself has described his projects as being fueled more by public service than by aesthetic design. Whereas many architects aim to create iconic buildings, he is largely concerned with a project’s underlying purpose.

In 2004 Aravena and his firm Elemental, who call themselves a “do-tank” (an activist’s twist on the term, “think-tank”) first gained international recognition with the Quinta Monroy project in the Chilean city of Iquique. At Elemental’s request the Chilean government granted them the task of solving the social dilemma of housing 93 families illegally squatting near the city centre. Rather than adhering to the standard practice of relocating the squatters to informal barrios outside the city limits, Elemental worked to settle them legally where they were. “We tested every single known typology available on the market”, the architect told author Justin McGuirk. “None of them solved the question. That’s why social housing is always two hours away on the peripheries. That’s the drama of Latin America.”

Elemental arrived in Iquique with only $7,500 per family in government subsidiaries, and with it they bought each family a plot of land and built them half a house. Without the funds to build each family an entire home, the idea was to build the framework equipped with the most necessary components, such as a living space with a kitchen and bathroom. Although Elemental’s concept was considered by many to be radical and controversial, it nonetheless proved a practical solution for the difficult situation in Iquique, and provided a fresh perspective for many urban planners and architects.

Centro Cultural de Constitución (elementalchile.cl)

The Pritzker Jury also saw in Aravena the same innovation he demonstrated in Constitución, Chile in 2010, when, after an earthquake and tsunami devastated the city, Elemental were given just 100 days to create a comprehensive reconstruction plan. Their project would eventually produce a new urban infrastructure, new public spaces, a new cultural centre, and a social housing project with a similar concept to that of Quinta Monroy.

Aravena’s radical thinking was also evident in his approach to future disaster prevention. Rather than build a concrete flood-wall to protect the city, a solution that seemed obvious, and favoured by the construction corporations that would receive the contract, Avarena planted a forest. “The experience of the Japanese tsunami of 2011 showed us that protective walls don’t always work,” said Avarena. “A forest, on the other hand, doesn’t try to resist the power of a tsunami. It dissipates the impact instead. In the face of geographical threats, you have to find geographical solutions.”

In Constitución, Aravena avoided becoming an unapproachable, outsider ‘starchitect’. Instead he set up an open house in the city’s main square where the community could participate in reconstruction decisions. Avarena encouraged local citizens to vote on what they thought was best for their city. “The point is that everyone has their own view. It’s not for me, as an architect coming from outside, to decide which is more important, a fire station or a bus station.” said Avarena. This type of open communication between architect and citizen was soon adopted by other urban planners and architects struggling with issues of integration in the sprawling favela and barrio suburbs in the major cities throughout the continent.

While the majority of Elemental’s work has been based in Chile, their portfolio also includes a winery in Germany, museums in Colombia and Switzerland, dormitories in the US, and a stock exchange in Iran. However, it was the buildings that Avarena designed and built for his alma mater, the Universidad Católica de Chile, which caught the eye of the Pritzker Jury, specifically the UC Innovation Center, which stands as an iconic image of his unique architectural style.

Centro de Innovación UC (elementalchile.cl)

The heavy and rough betón brut façades of the Innovation Center reference many of Aravena’s other architectural and public projects. Described by Alexandra Lange as “pre-ruins, with deep, shade-creating façades, generating the kind of monumental, sheltering spaces,” his projects often take on the appearance of oversized children’s buildings blocks or pre-historic monoliths.

The Innovation Center was constructed with a hollow central atrium, surrounded on all sides by layers of open, glass office floors. This transparent and open workplace interior was then encased with a mass of load-bearing exterior walls. Large staggered block openings were designed to interrupt the continuity of these exterior walls, allowing access to outdoor spaces throughout the building, and for natural light and ventilation.

However, according to Aravena, this innovative structure did not require rocket-science, sophisticated programming, or technology to create a proper workplace environment, but merely “archaic, primitive, common sense.” “And by using common sense, we went from 120 kilowatts per meter-squared, per year, which is the typical energy consumption for cooling a glass tower, to 40 kilowatts per meter-squared, per year,” according to Aravena. “So with the right design, sustainability is nothing but the rigorous use of common sense.”

While Avarena has, until recently, been relatively unknown, his public profile seems to be on the increase. He has served on the Pritzker Jury, and has now been chosen as Director of this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale, set to take place between May and November. With the Pritzker Prize now to his name, it is expected that more international attention and commissions will be knocking on Chile’s door, and Avarena may not be alone in answering. Robin Pogrebin has described Chile as entering a “time of critical mass in quality architecture,” a prediction Avarena has supported, saying he could name ten architects in his country of whose work he is envious.

Lord Peter Palumbo, the Chair of the Jury of the Pritzker Prize, said when the Jury visited Aravena’s projects, “they felt a sense of wonder and revelation; they understood that his is an innovative way of creating great architecture, with the best yet to come.” He later reached for the words of John Keats, and poetically concluded, “Stout Cortez stared at the Pacific with eagle eyes, whilst the Pritzker Jury felt like some watcher of the skies when a new planet swims into his ken: And although not silent upon a peak in Darien, they looked at each other with a wild surmise, captivated, stunned, and overwhelmed by the work of Alejandro Aravena and the promise of a golden future.”

You can watch the 2016 Pritzker Prize Award Ceremony live on April 4th at 7:30pm EDT in the US: webtv.un.org

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.