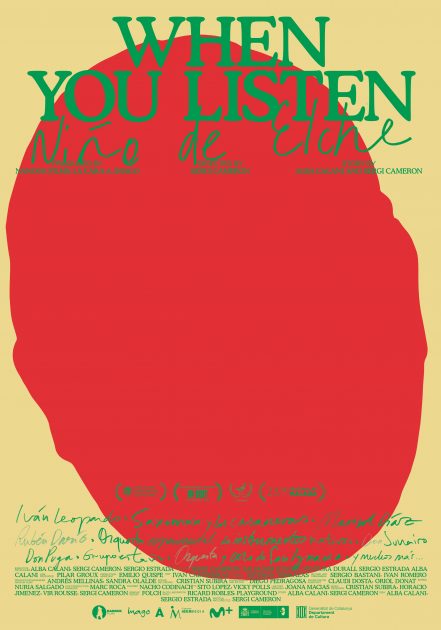

‘When You Listen’: Experimental Flamenco Musician El Niño de Elche Travels to Bolivia Without a Goal

28 October, 2020When You Listen (original title Niños Somos Todos, directed by Sergi Cameron, 2019) follows experimental flamenco musician El Niño de Elche (Paco Contreras) as he travels to Bolivia without a goal, looking to get closer to the creative processes of the country — and to do so as a child would do, “because the child plays, experiments, creates without a goal, without a concept of time.”

The film features beautiful cinematography, unconventional encounters and emotional musical performances, and the trailer is an exciting piece of experimental musical storytelling. But at its best, the film serves as interesting music content; and at its worst, it is an irresponsible travel documentary, where Bolivia and its people seem to have been randomly selected by the film-maker as a canvas for a reckless splatter of scenes.

The strengths lie in the film’s musical performances. El Niño de Elche duets with a millennial producer in the intimacy of his caravan in an erotic music-video scene; he joins hundred-mile-a-minute busker and YouTuber, “Saxoman”, in front of a green-screen; a young boy from the choir and orchestra of Santa Ana teaches him to sing in Guarayu as the passionate conductor leads them to great heights in a gaudy cathedral; and he teaches a young child to strum flamenco chords as he beautifully sings in that rasping, soft voice.

There are also some glimpses into lesser-publicised Bolivian musical cultures. As Contreras enters the country, we see Afro-Bolivians drumming and singing a saya in a main square. “If I was president, I’d build a bridge from Coroico to La Paz”, they sing, advocating the movement of people, ideas and opportunities between the Afro-Bolivian communities of the Yungas and the capital. In another scene, young musicians describe how the polyphonic sound of the pan flute reflects Bolivia’s plurinational status and over 35 different ethnic groups. On a roadside, an elderly musician blows leaves to a traditional tune and on a serene lowland lake, violinists play together on a rowing boat.

But When You Listen, the film’s English title, is a sentence never finished, as the film doesn’t listen long enough without interrupting. By overlaying seemingly disconnected musings about El Niño’s artistry with beautifully shot but unrelated images of Bolivia, the stories of this country are vacuously utilised as arbitrary decoration for a non-story about the artist. “Sometimes I’ll come up with projects so that I can travel”, Sergi Cameron admitted to RTVE, and this is plain to see. The following scenes will serve to demonstrate the point.

As Contreras descends into an Andean silver mine, invited by miners who describe to him the harsh conditions of their work, Paco’s voiceover (supposedly recorded in a studio post-travels) narrates his poor upbringing in Spain. It doesn’t exactly mar the miners’ accounts but it feels crass whacking these two stories into the same blender, before the fruits of each narrative – both individually valuable – are able to ripen. The juxtaposition of Spaniard Paco’s and the predominantly Aymaran Bolivian miners’ realities might make more sense if their two countries’ shared history were acknowledged, or even explored.

Once again, at the miners’ fiesta, the film fails to listen and instead overshadows the subjects’ reality. As workers and their families get drunk, dance and present awards, El Niño’s haunting vocals and discordant musical accompaniment are overlaid, distorting the melodías alegres of the celebration and imposing a feeling of doom on what could be seen as a moment of comparative joy for the miners. The fact is we can’t interpret the scene for ourselves, outside of the film-maker’s bias. We can’t enter into their reality enough to empathise, respect, feel. Notably, Paco copies the miners’ custom of toasting Pachamama before sipping each drink, but this culture is not explained. There is no exploration of the Aymara/Quechua customs that Contreras participates in, despite around 20 minutes of screen time later being dedicated to the strengths of being evangelised and the missionary church.

In another scene, stories of the film’s subjects fall on deaf ears. The passionate conductor of a children’s orchestra in Santa Ana in the Bolivian Amazon explains the great pride their orchestra has brought the town. They’ve won competitions and earned national recognition, which has allowed them to transform the town’s infrastructure and opportunities. The conductor emphasises the importance of recovering their region’s indigenous oral traditions and explains that the orchestra have begun to incorporate compositions by local virtuoso Don Januario into their repertoire, sung in Guarayu – an indigenous language spoken in Bolivia’s north-east – rather than Spanish. We later glean that this region has been heavily proselytised and there is a history – still withstanding – of missionary presence and evangelical thought. The local church is the Iglesia Misional de Santa Ana.

Yet El Niño’s intimate, poetic narration seems to stray drastically from the conductor’s point, negligently clouding what he has just highlighted. Paco instead centres the restoration and preservation of Jesuit compositions from the 17th century, sympathising with the Jesuits’ expulsion from the lands and romanticising the restoration of their musical compositions – which quite violently supplanted Guarayu songs. “They discovered […] a treasure that they needed to bring back into circulation, and reconstructed these scores that had been eaten away by damp and bugs,” he narrates. Over footage of local indigenous, black and mestizo musicians playing a variety of instruments, El Niño muses “There is no better mechanism for colonisation than culture”, which he attests is visible in that Bolivians have maintained the customs and the culture of the coloniser, in the Jesuits’ compositions they play to this day. It doesn’t feel like an alternative history is being offered in conjunction to the conductor’s, but rather that the (white, Spanish) film-makers have completely overlooked what their interviewees are illuminating.

An evangelist narrative is developed at the film’s perplexing close. The local priest in Santa Ana is the first in the film to address Paco’s ties to Spain as coloniser, directly telling him “What you brought us (…) was evangelisation.” This then sparks off Contreras’ remarks on the “inevitable” paternalistic feelings of a Spaniard in Bolivia as he falls into a harmful archetype: paternalistic European suffering from a colonial hangover. Surely El Niño de Elche, who has described himself as an anarchist, a revolutionary artist, a risk-taker and free thinker, can avoid this trope?

“You can’t calculate pain after 400 years,” Contreras meditates in the same breathy, awestruck tone, “My big question is: how much physical violence was there? […] it’s a bit difficult to imagine a Jesuit cutting someone’s head off. Changing the image of colonisation to evangelisation – and it’s not just Father Jorge who defends that, it’s also an idea in Europe – seems revolutionary to me.” When the film’s protagonist is presented as an artist who criticises religion, fights the repressive limits of purist flamenco and always searches for liberty, it’s confusing that the film ends with him condoning the evangelisation of Bolivian communities. This conservative, neo-colonial outlook reflects neither the musicianship of El Niño nor the Bolivians he’s met.

Not only does his comment make little sense – it’s clear that evangelisation was part of the pernicious, catastrophic, process of colonisation – but this view is noxious: the film publicly dismisses the cultural, emotional and physical violence that Jesuit missionaries caused throughout the “New World”. Remember that evangelisation projects continue to this day, ranking the ‘progress’ of indigenous groups by the extent of their evangelisation or their “need for spiritual renewal”, and posing serious concern over the spread of COVID-19, recalling the decimation of Latin Americans by smallpox and other European diseases from the 15th century onwards.

After the film won the grand prize at Italy’s Asolo Art Film Festival, director Sergi Cameron wrote (tr.) “I’m delighted not only about winning the festival’s grand prize, but also by the fact that our intentions with the film have been so well understood by the jury.” The jury’s perspective? “When You Listen by Sergi Cameron is a film that looks like an act of love towards the numerous human beings that the protagonist encounters along his way and that he does not observe with a judging or exoticizing gaze.”

Yet this is not the film I saw. Paco himself admits, as he travels in the back of a truck to a Mennonite community (assumedly also recorded post-production), that he is going there with prejudice, specifically after hearing from a shopkeeper’s family about a homosexual man in the community being caged for years on end. It’s been all over the press. Although Paco is there supposedly to discuss the community’s relationship to sound, given that music is prohibited outside of the church, it is both strange and coarse that he abruptly launches into asking his host about the cage incident as soon as he arrives. Our first entry point to the Mennonite community is this image of a cage, and although, as the shopkeeper states, they are Bolivians, their place in the country is left unexplored. Rather than being cast as another group making up Bolivia’s diverse population, they are analysed as an exotic (albeit white) other.

Once again the film-maker’s vision dwarfs the subject’s as Paco sings to the Mennonite family, rebelliously breaking the rules as the family looks on uncomfortably. When Paco finally relays his interest in the community’s everyday soundtrack, we hear a cacophony of baby chicks squawking around the host in a rather beautiful shot. Later that evening, when their host is drunk from the beer the crew have bought him, he eases up and says now he understands what El Niño was trying to tell him all along: that there is music in his every day. So Paco arrives with prejudice and leaves having spread the message he intended to bring. The evangelistic threads weaving this non-story together really do make it a troubling film.

I’m actually fond of El Niño’s rejection of a thesis to his travels despite the film-maker’s intentions. But a clearer premise – alongside deeper research and a serious review of the script – would have helped bind this radically messy montage into a cohesive film. Without it, the narration is pretentious rather than prophetic; El Niño’s reflections eclipse the stories of the individuals who invite him into their homes and Bolivia is pinned up as little more than a backdrop for an investigation into Paco Contreras’ artistic mind. Perhaps involving Bolivian crew members in the production would have alleviated some of these tensions. Language barriers can’t be used as much of an excuse here.

If you’re interested in musical exchange between Latin America and Spain and haven’t completely written off El Niño de Elche yet, turn to his 2019 album Colombiana, co-written and produced by Colombian musician, Elbis Álvarez of Meridian Brothers. This record delves into the influence of Latin America on flamenco music and although beginning naturally from his Eurocentric position, El Niño unconventionally explores this relationship in contraflow. Whereas Colombiana recovers the shared musical histories of Spain and Latin America, exploring drugs, colonialism, maize, cacao, labour, prostitution, slavery and more, When You Listen whirls around Bolivia without direction in a crazed, confused, irresponsible musing, which doesn’t seem in line with El Niño’s usual calls for freedom of thought and expression.

To counter the nonsense Contreras splutters in the narration, I’ll end on a stunning and revelatory Basque poem which he sings to Don Januario, elder and revered musician of Santa Ana. “If I had cut his wings, he would have been mine, he would not have escaped. If I had cut his wings, he would have been mine, but then he would have stopped being a bird, and what I loved was the bird.” The upside of this film is that plurinational Bolivia once again eludes definition, as the film-makers only reinstate a stereotype upon themselves.

Niños Somos Todos (When You Listen) was produced by Nanouk Films (SP), Imago (BO) and Alba Calani.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.