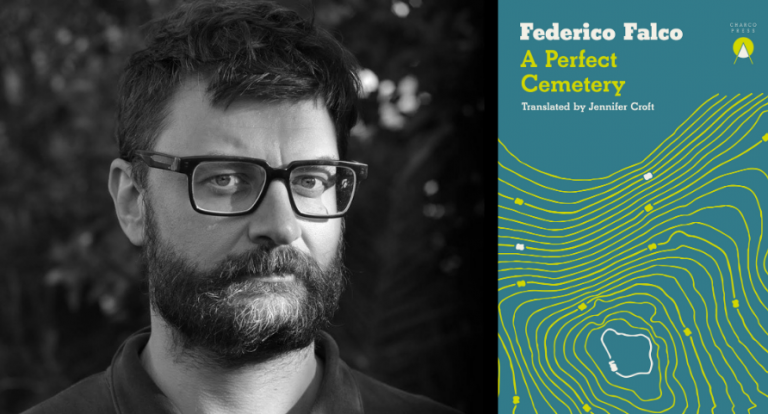

Landscapes, Hermits and Storytelling: An Interview with Federico Falco, Author of ‘A Perfect Cemetery’

08 April, 2021Federico Falco, the award-winning Argentinian novelist, short story writer and poet, is publishing his first work in English this month with Charco Press. A Perfect Cemetery is a rich, sophisticated portrait of rural life and its complexities, largely set in Falco’s native province of Córdoba. The collection of five stories explores notions of community, intimacy and solitude in isolated places, and displays a fine attention to the bonds people form with the natural world around them. Sounds and Colours spoke to Falco about the collection, the literary footprint of the Argentine interior, the power of landscape to form us, and why the state of short story writing might benefit from a shake-up.

With thanks to Carolina Orloff at Charco Press for the English translation of this interview.

A Perfect Cemetery is rooted in your own native province of Córdoba. How much of your own life experience is in the stories?

Some of the landscapes in these stories could easily be identified as landscapes from the province of Córdoba, especially its mountainous areas, but in reality, in my mind they worked more as a patchwork of landscapes in different places that I longed for at that moment and that, thanks to fiction, I could bring together as if they were contiguous. Over the years I wrote these stories I was living a fairly nomadic life, living almost always in big cities and filled with nostalgia for natural landscapes: those of my childhood in Córdoba, but also some of the forests in the north of New York State, or in Patagonia. I had lived in these landscapes, sometimes for brief periods, but they left a deep impression on me, and in some way, by writing about them, I wanted to recover them, I wanted to inhabit them again even if only during the writing process. That is why, rather than my own experiences, these stories contain memories, evocations, even fantasies about these places that I was missing.

In a review of A Perfect Cemetery for the TLS, Kit Maude mentions how rare it is in Argentinian literature to focus on the interior of the country. Why do you think this might be – if it is indeed true –, and is this tendency beginning to change?

In the very origins of Argentine literature there is a certain tension between the urban and the rural, the capital and the interior, “civilization and barbarism”, to put it in Domingo Faustino Sarmiento’s terms. It is something that was always there and, in different periods, throughout the twentieth century and the start of the twenty-first, different ideas or clichés were associated with the landscapes of the interior: the wild or uncivilised desert of the interior; but also the interior as a place of escape: an idyllic, almost archaic interior, a kind of unaltered paradise to return to and take refuge from the chaos of urban life; or the interior that is a kind of little hell, that of the novel of manners, with its gossip and its small lives full of small-town pettiness.

In the twentieth century there are great writers who evoke the interior: Antonio di Benedetto, Sara Gallardo, Juan José Saer, Manuel Puig, to name only a few. It’s true that, if we think about the literature written in the ‘80s and ‘90s and also after the crisis of 2001, above all the literature written by the younger generations, most of them have an urban background, and perhaps we come from a period, a number of years where that background predominated. But I also feel that this trend has seen more nuance for a while now. If we take the decade between 2010 and 2020, many of the names that I find most interesting write about or are from the interior: I’m thinking of Selva Almada, Hernán Ronsino, Eugenia Almeida, Luciano Lamberti, Mariano Quiroz, Pablo Natale, Hernán Arias, Marina Clos, among many others.

There is a real sense of solitude and isolation in a couple of the stories. I’m from a small, rural community myself so I related to a lot of these themes. How important was it to create that sense of people being shaped by living in this isolated part of the world?

For me, the landscape in which we live, in which we spend our days, has a vital importance: it forms us, it transforms us, it shapes us, shapes our dreams and ambitions, makes us feel at home or makes us feel like outsiders, it gives us ambitions, puts us in contact with a particular kind of life. This is an aspect that naturally I pay a lot of attention to. I was born in a small town in the pampas of Argentina and lived there until I was 18. A good part of my childhood was spent in the country, I know these places, I know the people who inhabit them, I know their work, the way they organise their days… Somewhere, I myself am – I continue to be – one of these people. Writing about these kinds of spaces is something that arises almost naturally for me.

You’ve spoken before about your interest in the figure of the hermit – and a great example of this is Oscar, the protagonist of the first story, The Hares. Why do you feel such interest in this archetype?

During my childhood I knew a few people who could fit this archetype of the hermit. Older people who lived in isolation in the middle of the countryside and who were a source of great intrigue to me. At that time, to my child’s or teenager’s eyes, their silence was a mystery I tried to reveal: was it a silence that indicated wisdom or a silence that suggested a paltry inner life? Since then, it has been a type of character that attracts me a lot: the character who chooses solitude.

Later on, other questions arose around the same figure: how can you be yourself if you constantly live for others? How to establish a dialogue between a solitude that is sometimes necessary and life in community, the connections and networks that sustain us as human beings? Does the hermit represent a complete abandonment of the world, a burning of bridges, cutting off connections, or on the contrary is it about the discovery of a greater union with the world, a purer or simpler union with a wider world? These are issues that I find fascinating because in some way they illuminate my own quest, the questions I ask myself about my own way of life.

Why did you decide to name the collection after the third story, A Perfect Cemetery?

I tend to write several stories at the same time, but in this book in particular, A Perfect Cemetery was one of the first stories I finished and I felt that in some way there I’d found a certain tone and a certain world that propelled me to carry on with the other stories. I instinctively felt it as a kind of nucleus around which the other stories began to order themselves. On top of that, I like this contradiction between the idea of the cemetery and of perfection, there is something about this combination of words that even creates a certain mystery for me, and that’s why I chose it as the title of the volume.

The collection is very well-translated by Jennifer Croft. What was the process like of converting your work into English?

Jennifer is someone I greatly admire, as a translator and as an author and for me it was a great joy and honour that she took an interest in translating these stories. Jennifer isn’t only brilliant, she is also highly professional and meticulous in her work, and apart from a few specific questions and advising me of some choices she’d made about how the characters speak – decisions that I felt were not only accurate but illuminating – I only read the final version of each of the stories as she sent them to me. It goes without saying that I hardly had any suggestions to make, and could just enjoy the astonishment of reading in another language, and in such a fluid and natural manner, these characters and landscapes I know so well.

You’ve spoken before about the need to “drag the short story out of its ossified and predictable state”. Could you define why you see the state of story writing in this way, and how you try to move beyond it in this collection?

The short story is a genre that – above all in its more formal aspects – always runs the risk of falling into a structure of repetition. Sometimes, instead of allowing the story to find its own form and its own way of unfolding, what we try to do is force it into a formal mould that we already know: we construct it according to this mould, the structure that we feel a story should take, or what certain publishers and magazines say a story should be.

Often, the very definition of what a story is comes from this formal structure, and it’s not always something we can avoid, but I do believe it is a worthwhile challenge to try. That’s what I proposed to do in this collection, in a way: allowing the plots to grow under their own power, to expand and overflow and gradually, like water, find their own course.

Click here to read Will Huddleston’s review of A Perfect Cemetery.

A Perfect Cemetery was translated by Jennifer Croft and is published by Charco Press. It is available to purchase via Sounds and Colours’ page on bookshop.org.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.