‘The Soul of a Woman’: Isabel Allende mediates on feminism, inequality, aging and love

08 March, 2021Isabel Allende was born in Peru and raised in Chile. She now lives in California. Following a career in journalism and exile in Venezuela, she published her widely acclaimed novel The House of Spirits in 1982, which paved the way for her to achieve literary stardom. Many of her bestselling novels are centred around the extraordinary lives and experiences of her female protagonists. Her work has been translated into over 42 languages, and she has been described as the world’s most widely-read Spanish language author.

In The Soul of a Woman, Allende’s latest memoir, she speaks of events in her lifetime, from personal to geopolitical, and how they have influenced her feminist beliefs. She begins with how her mother Panchita was abandoned by her husband, leaving her to care for three young children. She mentions how the military coup in Chile, leading to her exile in Venezuela, impacted her life significantly. She also speaks honestly about her own family life: the death of her daughter Paula when Isabel was in her fifties, her two divorces (one when she was in her seventies) and finding new love afterwards with her third husband.

“When I say that I was a feminist in kindergarten, even before the concept was known in my family, I was not exaggerating.”

I had to quote the opening line of The Soul of a Woman because I couldn’t explain the book’s direct and powerful tone any other way. In The Soul of a Woman, Allende talks frankly about everything she has to be grateful for, though details many societal problems that make her worry about the state of the world. I am very grateful to have had Allende’s voice carry me through the pages of direct and personal writing that, of course, has got in it her heart and soul. She says (quite mischievously) that this is just an informal chat, but there’s no doubt that Allende’s strength of mind is something to be celebrated. The memoirs are arranged in short, thematic passages that are conversational in tone but comprehensive in subject matter.

“[The] era of emboldened grandmothers”

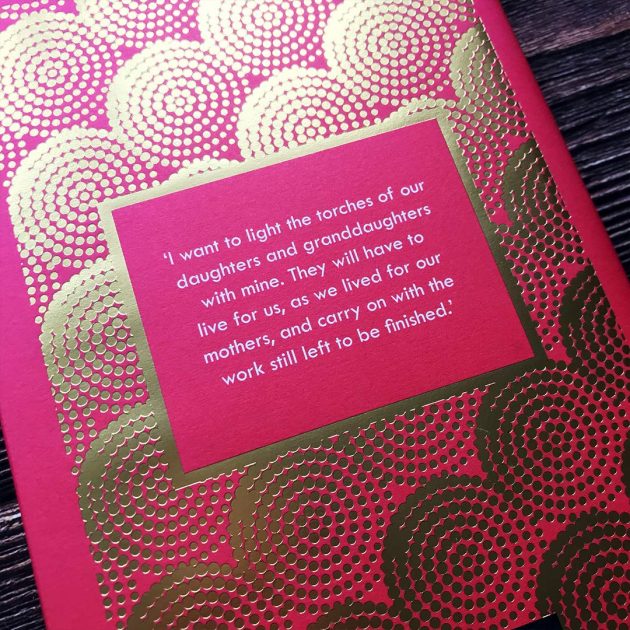

The Soul of a Woman gives as much contemplation to the experience of ageing as it does to meditations on gender politics. I felt that the book put forward a very welcomed form of intersectionality by championing the “era of emboldened grandmothers”. She writes that contentment comes from forgiveness of others and ourselves, that she can overcome fear by being active forever, and in making a call for solidarity amongst women of her generation, she reminds us of the immense value of friendship. “I am not going to retire” she writes (having already pointed out that the Spanish word for retirement, jubilación, is wishful thinking), “I am going to renovate”. Her energy, and the inspiration she takes from her own female role models, is incredibly fun to read. I read Allende’s most recent novel A Long Petal of the Sea (published in English in 2020): a novel about characters who live remarkable lives, reinventing themselves as they cross borders and cope with immense challenges. It was a pleasure to read Allende’s most recent memoirs after reading A Long Petal of the Sea, and to understand more about the remarkable life (or lives) Allende has herself lived. And, of course, A Soul of a Woman shows us that a full life does not at all mean that there is any finite capacity for passion or love.

“There’s no feminism without economic independence”

“There’s no feminism without economic independence” writes Allende, and there is no shortage of examples she gives us of the socioeconomic situations that face women, girls and disadvantaged members of this world. From violence, to many devastating forms of exploitation, to poverty, to lack of education, to prejudice, to machismo, to struggles for access to medical treatment, we can’t forget the adversities that might crop up at any point in life, or more problematically be baked into someone’s situation from birth. The long list and the types of hardship described in Allende’s reflections admittedly make me feel quite helpless, and then overwhelmed. Allende does offer some hopeful stories, though, such as the work by her own role model, Olga Murray, who was the founder of the Nepal Youth Foundation, and she asks us to “please look up Olga Murray online”. There is plenty of fertile ground here for conversation-starters and motivation to get involved in charitable causes, and so perhaps some hope.

Speaking of her experience building a career in a male-dominated publishing landscape in Latin America, Allende notes the noun and verb chaqueteo and chaquetear (meaning to grab someone by the lapels and pull the person down) could play out with different amounts of cruelty and at varying speed depending on who is subject to the action, and she suggests that she saw women in the publishing industry who had to battle the harsher end of this scale. She makes a similar point that many aspects of tradition, or cultural standards, and of course the language attached to them are not applied or interpreted in accordance with gender equity. For example, she suggests if a man is beaten and deprived of freedom, it’s called torture, whereas if a woman endures the same, it’s called domestic violence. While (as she admits herself) there is an element of generalisation at times in the book, her pointing to inconsistent standards is a useful prompt for further reflection.

“The patriarchy is stony. Feminism, like the ocean, is fluid, powerful, deep and encompasses the infinite complexity of life; it moves in waves, current, tides and sometimes in storms. Like the ocean, feminism never stays quiet.”

This book gives us the soul of a woman and here we see the breadth and depth of one woman’s feelings. It is also extremely interesting to note that the Spanish title, Qué queremos las mujeres, refers to ‘women’ in the plural. I learnt a lot from reading A Soul of a Woman, which is an impassioned, and romantic, reflection on what it means to be a woman and a feminist in the world.

The Soul of a Woman, translated by Nick Caistor and Amanda Hopkinson, is published by Bloomsbury in the UK and Penguin Random House in the USA. It is available to purchase on Sounds and Colours’ page on bookshop.org.

The Isabel Allende Foundation, founded by Isabel Allende to honour her daughter Paula, Frias is guided by a vision of a world in which women have achieved social and economic justice. They invest in the power of women and girls to secure reproductive rights, economic independence and freedom from violence.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.