Chapter 2: Quiero Conectarme a La WiFi

08 July, 2016Day 2: 2nd May 2016

After breakfast, I leave the casa particular shielding my eyes from the bright sun as I lost my only pair of sunglasses at some point in yesterday’s airport-guagua shuffle and there doesn’t seem to be anywhere around town where I can pick up another pair.

Instead, I turn my search to Wi-Fi.

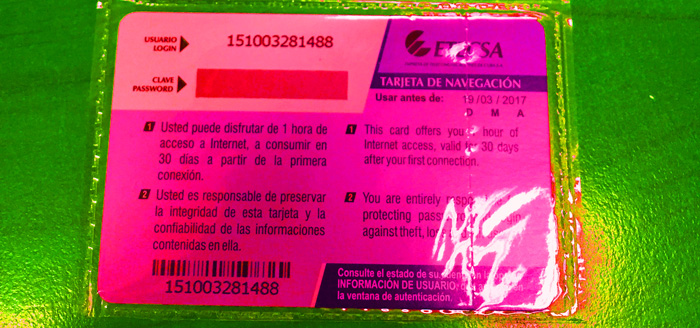

Private home internet access is virtually non-existent in Cuba except for embassy residences and for those with government connections. Often what you’ll find is dial-up modems, so most people only have the option of connecting to newly established government Wi-Fi networks in public parks and plazas with access cards purchased through ETECSA, Cuba’s national telecom. At the first ETECSA kiosk I find, I purchase three Wi-Fi cards with an hour of connectivity each for 6 CUC and circle around the corner to Plaza Céspedes where locals and tourists sit scattered on benches, and stare into phone and tablet screens.

In Cuba, even the internet is an outdoor activity.

I spend an hour or so checking social media and posting an obligatory old car photo, then head in the direction Café Dranguet, Manana Festival’s information hub, and run into Natalia Linares, the festival’s Cuban-American press coordinator on the way. She briefs me on the day’s activities and somehow during our conversation, we end up trading her sunglasses for my internet cards; bartering, I will soon learn, is standard practice in Santiago.

Time to check in at my new home for the week: a 1950s style two-floor casa particular called Casa Marmol, sourced through Airbnb. My room is clean, simple, and frosty with air conditioning. I unpack and gather my various digital media devices to catch the rehearsal of an artist called Gifted and Blessed at Iris Jazz Café that Natalia mentioned to me earlier. Shuttling around the city in taxis can get expensive, so, for a fraction of the price, I hail another moto-taxi and pull out my camera to record the experience in 360 degrees:

Iris Jazz Club is empty, save for the barman at the front. I ask if this is the right place and the barman says yes, just that nobody has arrived yet ; we’re on Cuban time. I can’t resist ordering a mojito while I wait, setting up my recording gear in the performance hall, which is dimly lit with dark wood panelling and a psychedelic mural of strange-looking horns blowing out a whirlwind of multi-coloured geometric shapes. There’s a photo-wall of famous jazz musicians, many of whom have graced this very theatre. Onstage there’s a piano, a drum set, some congas and a set of batá drums.

Gabriel Reyes-Whittaker, aka the musician Gifted and Blessed, in from Los Angeles, shows up with a backpack full of gear including an Elektron Octatrack drum machine/sampler and an Analog Four synthesizer/sequencer, donated to the Manana Festival by the Swedish electronic musical instrument company Elektron to foster collaborations exactly like the one whose genesis I’m about to witness:

Gabe and his two Cuban collaborators jam for about an hour so, in what appears to be a somewhat unfocused, but still compelling, mixture of sequenced electronic drums, jazzy, modal Bossa-flavoured chord progressions by GB via the Elektron, piano solos, live break-beats and Latin-jazz fusion beats on drum set and percussion. Though I’m thoroughly enjoying the music and mojitos, I’ve been here for hours and have got to move on and see what else Santiago has to offer this evening.

In the main lobby, I check to see if I can pick up the Wi-Fi signal from Plaza Martes across the street. Another tall white Yuma (Cuban for “gringo”), also on the hunt for Wi-Fi, sits nearby and we get to chatting about music and our hometowns. He’s Aaron Liddard, from London, and his friends in the group called Ariwo have invited him here; a musician, like myself, but not playing at the festival, or at least not officially. We talk over a couple of beers, until interrupted by what sounds like a large percussion ensemble playing outside in the plaza. We step out to see what’s happening in the square and come across a comparsa called Tambores De Bonne. They are not performing at Manana, but the music is typical of the type of Santiaguero folk ensembles that are gracing the schedule.

“Comparsas are large ensembles of musicians, singers and dancers with a specific costume and choreography which perform in the street carnivals of Santiago de Cuba and Havana. Congas santiagueras include the corneta china (Chinese cornet), which is an adaptation of the Cantonese suona introduced in Oriente in 1915, and its percussion section comprises bocúes (similar to African ashiko drums), the quinto (highest pitched conga drum), galletas and the pilón, as well as brakes which are struck with metal sticks)” — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conga_(music)

Aaron and I eventually part ways, and after about four blocks walking along Calle Enramadas (Street of Tabernacles), the main commercial promenade stretching from one end of downtown Santiago to the other, I manage to get hooked into one of Cuba’s most common tourism schemes: the impromptu tour guide posing as your new best friend.

Two wiry black men with ruddy but friendly faces approach me asking if I like live music.

“Sure,” I say, a little suspicious, but interested given that this is the entire purpose of my visit here. “Why?”

One of the guys, who claims to be a dance teacher, tells me that close by a great music ensemble is playing Son Rumbero. I decide to roll with the guys to the bar. It’s early evening on a well-lit street with plenty of people everywhere. I feel like these guys will probably end up asking me for money at some point, but for now, I’m just killing time.

They must sense my American caution, though. To reassure me, the more talkative one pulls out his Cuban national ID (carnet) to show that he is, in fact, a registered, government-approved dance teacher. Then his friend pulls out his own carnet proving that he, too, is a registered teacher: of boxing.

The bar is, of course, a total tourist trap, with a mediocre band. I’m hungry, and the guys tell me about another place, a nice restaurant with live music too. I’m a little sceptical of their tour guiding skills at this point, but we head over, and I buy the guys a couple of beers for their services. We talk about life in Santiago and the music scene here compared to that of Havana, while a young woman and old man playing a guitar perform old Cuban boleros.

The dancer and the boxer tell me how hard it is to make a living as a salsa instructor and as a boxing coach who, though a former pro, has suffered too many concussions.

I notice the dance teacher wears a green and yellow beaded necklace and bracelet, for the orisha Orúnmila, syncretized with St. Francis of Assisi, for protection from death arriving at the wrong moment. The conversation shifts toward Santería, then to Fidel, about whom the dance teacher repeats a popular local rumour that the reason Fidel has lasted so long and survived so many assassination attempts, never losing his power over the island, is because he’s a secretly a babalawo, a priest of Ifá.

I’m fairly sure the rumour is apocryphal but who knows: it’s not like there’s a free press in Cuba to either confirm or deny the rumour and it’s probably worked to Fidel’s advantage to neither confirm or deny it.

As expected, when we head back to the Plaza Céspedes sometime around midnight so I can catch a moto-taxi home, the dancer and the boxer reveal their hustle by making their pitch to me for some cash.

No sob stories though. They tell me all they want is to be able to buy a bottle of rum to take to a party.

I respect their honest hustle and give them 5 CUC, thanking them for showing me around.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.