‘I don’t want the reader be able to escape this book unharmed’: María Fernanda Ampuero on ‘Cockfight’

30 September, 2020[Lee en español aquí]

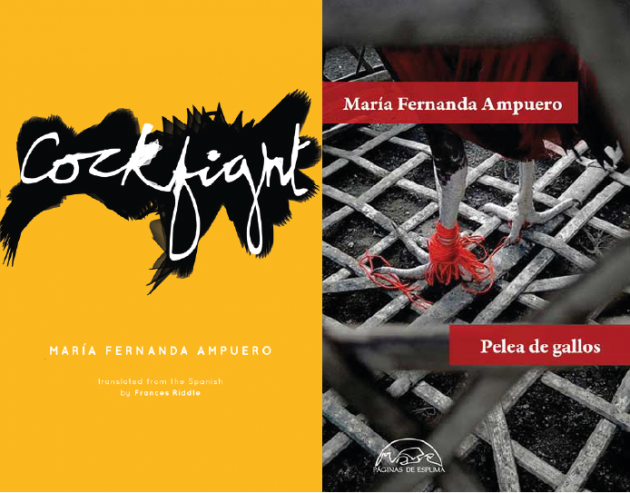

Award-winning Ecuadorian writer, María Fernanda Ampuero, released her first collection of short stories last month with Feminist Press. Not for the faint-hearted, Cockflight is a gory, gruesome collection of nightmares and fairytales that coldly narrate the lives of contemporary Latin American women. The collection unflinchingly offers a window into the home, speaking through the perspectives of a range of women in 13 different short stories. We spoke to the author to learn more about her storytelling.

The collection begins with two quotes, one of which (“Am I a monster or is this what it is to be human?”) is from The Hour of the Star by Clarice Lispector – a novel about a woman who lives an outwardly miserable life and endures physical and emotional violence, but whose narrator recognises that she enjoys a sort of inner freedom. What drew you to pick this quote to open the collection?

A beautiful thing happens with epigraphs, because somehow, they summarise the entire book, don’t they? They summarise what the author believes their book to be. So your choice has to be very accurate and you have to have a special connection to the quote. I feel very close to Clarice Lispector’s narrative universe so this made it very easy to choose her work, but I also think this choice had something to do with the recurrence of a child’s way of thinking throughout my book. Perhaps this question that Lispector asks, “Am I a monster or is this what it is to be human?”, is one that I asked myself many times throughout my childhood – when my sense of self was still being formed and suddenly you have these scary thoughts that you think no one else has.

The other quote that begins the collection is from Fabián Casas, saying “everything that rots forms a family”. Was there reason behind choosing these authors, as well as the quotes themselves?

In regards to Clarice Lispector, yes, because as I said before I have this very special connection to her; I feel like we have similar obsessions, pains, worries, quests. The Fabián Casas quote, conversely, was more – how can I put it? – magical, because it was at the time that I was putting the book together that I heard this quote. It was used during an interview with him and it hit me like a bullet straight to the heart. “This is it” I thought, “this is exactly it!”. I think that both quotes summarise the book very well and ‘converse’ perfectly with what I want to demonstrate in my short stories.

Did you always envisage Cockfight as a collection of short stories? Why did you choose this form?

This question requires hours of conversation because really Cockfight never existed in my head until I found the right people. I want to make it clear that although I am the mother of the book, Cockfight has a father and another mother. I’ve written fiction since I was small, but for various reasons (fear of being criticised, imposter’s syndrome, negative comments about my writing when I was very young) I never thought about publishing what I was writing in private. A few years ago I began to participate in some writing jams for fun and I started to do well, so I risked it and took part in a few competitions. I won them and garnered certain attention from it, which resulted in a literary agent, Amauir Fernández of International Editors, asking if she could read my stuff. That’s where it all began, like in a children’s book: with a fairy godmother. She helped me put together a book that we sent to different publishers, but the one that made me most excited was Páginas de Espuma. Juan Casamayor, editor at Páginas de Espuma, liked the book, worked on it with me, we edited it together and well, the result was this incredible journey called Cockfight that now has six Spanish editions, one Mexican edition, one US edition, and in 2021 there’ll be a British edition. Not to mention the Portuguese and Greek editions that will come later.

The stories in Cockflight are gruesome, shocking and sordid. Did you want to shock your readers? Are these tales modern-day Latin-American Brothers’ Grimm fairy tales, perhaps some of them fables?

Warmth is something I’m not fond of. In fact, my favorite phrase in the Bible is one from the Book of Revelation where God says “Those who are warm I’ll vomit from my mouth” [“So because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of My mouth]”. I don’t like euphemisms either. When it comes to writing, the last thing I want to do is hide. The stories might seem obscene, insufferable, or as you say “gruesome, shocking and sordid”, but they don’t leave you indifferent and that is exactly what I want. I couldn’t bear it if my readers remained neutral in regards to the topics I write about in my literature, that falling into the hells of abuse, pain and violence wouldn’t change them even a little bit. I want the reader to not be able to escape this book unharmed. What’s more, I think these feelings that you’ve described allow you to remove the blindfold, and we need people to remove the blindfold. We urgently need them to.

You’ve said that Cockfight aims to question the “most obscene institution that exists today”: the home. Could you elaborate on this and explain how the collection challenges this institution?

This concept of the family being sacred and untouchable seems absurd to me in this day and age. We’ve demystified almost all the institutions: religion, state, army, but we continue to view the family as an unquestionable institution and what worries me is that anything which can’t be questioned easily becomes totalitarian, fascist, dictatorial. I worry that the whole “you should honour your mother and father” idea exists just as it did centuries ago, even though we know that our fathers are fallible, obsessive, ridiculous, violent, failures just like us. They do what they can and they make mistakes far more often than they let on. I think that if we were able to question this sacred concept of family then we could establish some different rules to play by: rules that are more horizontal and based in mutual respect and communication. We’d be able to heal the wounds of so many people who keep wondering why their parents didn’t love them. The wounds your family leave you with are never cured, they open again and again, they rot and they never leave you in peace. Don’t you think this has got to change?

Many of the stories are written from a child or an adolescent’s point of view. Why was this important in the narration? House maids also feature in a number of the stories and offer a crucial insight into family matters. Why was it important to include their presence?

I’m obsessed with adolescence as a vital moment. It’s a frontier phase, and frontiers fascinate me: they’re one thing and then another, but also neither, but also both.

“In adolescence, the door is creaking from childhood into adulthood, and everything that happens to you at this time becomes incredibly transcendental: love, pain, everything feels ablaze, it’s the most cinematic, most literary moment of our existence and that’s why I’m interested in visiting it in my literature.”

Domestic workers are indispensable and fascinating to me. Coming from a society like Ecuador’s it’s impossible not to notice these women who share our whole existence, who act as a mother to babies and as a daughter to the elderly. We’re talking about people who share much more of your life with you than your parents do, who are witnesses to all the good, the bad and the abject parts of our existence, who know all of our secrets and who, nevertheless, are mistreated, abused, ridiculed, badly paid and discriminated against. It was very important to me that they had their own voice and were narrators.

Your prose is often sparing and precise. Could you tell us how you decided to use this style of writing, and why? Do you think your journalistic work has informed your literary style?

Yes, I’m sure my journalistic work has affected my storytelling, making it “sparing and precise” as you say, but it’s also given me a way of seeing things for what they are, and inviting the reader to “see” it with me without disguise or concealment. Making the reader a participant in what you’re narrating, through corporeal descriptions that hit the senses (colours, smells, textures) is a resource that I learned writing journalistic chronicles. I was lucky enough to have magnificent editors that helped me sharpen my gaze and polish my storytelling so that I could turn words into something physical, something tangible.

Many of Cockfight’s female characters rebel against their lot in life by reappropriating the violence that’s been committed against them. Was this a key element for the book?

I always wanted to create a superheroine, someone like Wonder Woman, but I don’t know how to write superhero literature, so I had to think about how to create a realistic woman with powers. Take the protagonist in Auction, for example, who uses what she learned in childhood about how disgusting men can be, to save her life. She is my heroine. She doesn’t have a magic lasso or invisible wings, but she has knowledge and, like witches, manages to disgust and scare people into leaving her alone.

In ‘Blinds’, a mother asks her son if he wants to marry her. He follows, “Everyone’s abandoned me, so I say yes”. What observation were you making about mother-son relationships in Latin America?

The story you mention has a special place in my heart, because it talks about an adolescent male who’s on the path to becoming a man, but he doesn’t want to, he doesn’t want to repeat the models of masculinity he’s learned: men who abandon, who cheat, who forget, who don’t love. He has a lot of love and that’s his downfall. What’s the fate of soft-hearted men? This young boy is like a wounded bird crying out for help that no one gives him. His mother, meanwhile, is an abandoned woman, a woman who also loved but it was unrequited. Mother and son are bonded by the need to be loved and this most bestial desire turns them into abject beings. She does the unutterable with her own son and he accepts. Why? For love. This story talks about the desperate, irrational, blind search for love that turns us into monsters.

Cockfight has been translated into English and is set to be translated into Greek and Portuguese. What was your role in its translation, are you happy with it and would you have allowed it to be translated by a man?

Francis Riddle’s translation process into English was a delight. We had various conversations whilst she worked on the translation and for me it was fascinating watching her convert something that was so mine – that belonged so strongly to my personal language – into something else, into something that belonged to English as if it had been created in that language. I think this is what good translators do, they make a text a citizen of another language, and of course doing this requires technique, knowledge of both languages and a sensitivity that I marvel at. What Frances did was a titanic work, in order to understand me and understand the environment in which these stories develop. A translation has to work with words, but also with the unsaid. A good translator also translates the blank spaces, the air, the atmosphere. I’m happy with the result. And, of course, male and female translators with Frances’ sensitivity are very much welcome.

Cockfight, translated by Frances Riddle, is published by Feminist Press and is available to purchase at Blackwells (UK) and Bookshop (USA).

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.