Transitional Justice in Peru

04 October, 2012Rebecca K. Root’s Transitional Justice in Peru is a thoughtful account of the human rights abuses which arose from the usurping of democratic institutions, the militarisation of political and legal processes and the murderous activities of the Sendero Luminoso/Shining Path between 1980 and 2000.

Institutionalised failure

Peru’s fragility as democratic state is a matter of historical record. Since independence from Spain in 1821, it has spent half the time under military rule. Its institutions are vulnerable to corruption; its political parties – a rich confection of vested interests; its military overbearing and unaccountable to civil law – and the constitution is as reassuring as a chewing gum wrapper.

The writer Mario Vargas Llosa noted during this period that there are “two Perus, one living in the 20th century – the other living in the 19th or 18th century.” They are worlds apart in language, culture, education, opportunity, wealth, health, and access to justice.

Cause and effect

Root looks at the golem set loose on Peru between 1980-2000 (under presidents Belaunde, Garcia and Fujimori) and the attempts by politicians, diplomats, NGOs (National Co-ordinator of Human Rights – Coordinadora, Mesa de Diálogo, Transparencia, Asociación Nacional de Familiares de Secuestrados, Detenidos y Desaparecidos del Perú – ANFASEP, Asociación Pro Derechos Humanos – APRODEH), INGOs (Amnesty International, International Center for Transitional Justice, Human Rights Watch, Centre for Justice and International Law etc.), UN Human Rights Committee, UN Working Group on Forced Disappearances, the OAS, Inter-American Court on Human Rights and others to deal with the repercussions of a state which for 20 years incarcerated, abused, tortured, killed, raped and systematically stripped its own citizens of their human rights whether they were guilty or not.

Fighting fire with fire

The pretext for the representative state to act unaccountably was the 1980 armed insurrection of Abimael Guzman’s Sendero Luminoso, a Maoist-inspired revolutionary organisation even more adept at terror and human rights abuses than the state it sought to overthrow. Indeed, it was to account for over half of the 70,000 deaths known to have occurred during this period.

Beatriz Alva Hart, a Congressional deputy and member of the Fujimori bloc, who later served as a lawyer on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), said: “When they hit us on our own turf, killing high-class white people, all of a sudden Sendero Luminoso became real. The reaction was, ‘Kill them all and forget human rights.’ That’s how people felt then.”

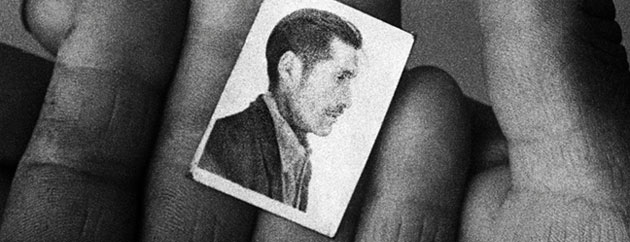

Most of the victims, like most of the perpetrators, came from Peru’s impoverished interior and were tawny-skinned, indigenos who spoke Quechua rather than Spanish. When Amnesty International first started blowing the human rights whistle in 1980, President Belaunde accused it of being “a tool for the destruction of Peruvian democracy”.

Fifty shades of immunity

The book explores the origins of the process of transitional justice in the aftermath of the collapse of the Fujimori government in 2000. It looks at the formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (CVR), its attempts to bring about truth, justice and reconciliation and its failed attempt to bring the Peruvian military within the scope of the civil legal code. It analyses the particular issue of military immunity from prosecution for human rights abuses, which is no longer defensible in International Law. The peculiarities of the Peruvian political system also means that both the electorate and politicians believe that justice is divisible into ‘guilty’ and ‘innocence’ and only the innocent are entitled to human rights. The upshot of this, of course, is that there are real fears – shared by the author – that all the conditions are still there to re-run the very issues that gave rise to the militarisation of the state and the emergence Sendero Luminoso in the first place. Needless to say, the politicians pull out the ‘terrorist’ card at every turn. The question remains, though, how can you uphold justice by ignoring or subverting it? You can’t – but nobody in power seems to care.

Setting free and tying up

From 22nd November to 28th July, 2001, interim president Valentín Paniagua was able to set up – with able NGO support from Sofía Macher, Salomón Lerner – the Comisión de laVerdad y Reconciliación/Truth and Reconciliation Commission – CVR, among others. Whatever history might say about its successes or failures, it was a remarkable achievement under the circumstances.

Fujimori’s autogolpe/self-coup, as Root writes, had effectively stripped out civilian government to make way for a de facto military state. The Organisation of American States (OAS) looked on powerless. Only with the congruence of electoral fraud in the run up to the 2000 presidential election (and the popular unrest it provoked), the emergence of the ‘vladivideos’ – Vladimiro Montesinos’ video nasty collection which along with testimony (on route to exile) from General Rudolfo Robles implicated the government in the activities of Grupo Colina (death squads) and widespread fraud, embezzlement, murder, drug trafficking, etc… things started to unravel.

The Truth and Reconciliation Comission (CVR), as Root attests, managed to make great strides in “locking in” Peru’s recovering democracy into international norms which enshrined respect for human rights in law. Indeed, it was no small achievement that in 2009 Peru became the first state to try and incarcerate a democratically elected president (Alberto Fujimori) on human rights abuses.

Now, ironically, Abimael Guzman, Victor Polay (leader of the Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru (MRTA), the two principal terrorist leaders reside – with former President Fujimori and his erstwhile team of Vladimiro Montesinos (head of the appropriately named, SIN – Servicio de Interior Nacional) and Julio Salazar Monroe, architects of Grupo Colina and all round crooks and murderers – in the Callao Naval Base prison built by Fujimori to house Category A prisoners.

Justice out on a leash

The massacres of Accomarca, Barrios Altos, Ancash, Lacanamarca, La Cantuta, Putis, Tarata etc., – the work of Sendero Luminoso, MRTA and Grupo Colina – some of which involved large numbers of children – are the spectres at Peru’s post-emergency feast. As Root describes, the country and the international community have made it much more difficult for politicians to make up their own moral code. Those assaying the issue of military justice applied to civilians and the scope and jurisdiction of military courts ought to remember the words of General Nicolás de Bari Hermoza, army commander at the time of the La Cantuta University case. After a professor and nine students were murdered and their bodies incinerated, he said there was “insufficient evidence that the La Cantuta students had ever existed”.

A warning from history

Root – like many in the human rights field – sees that the co-operation and collaboration offered immediately post-Fujimori is ending. The present political climate is one in which optimism is being replaced by political cynicism, populist posturing and foot-dragging. Nowhere is this more evident than on the issues of exhumations; reparations (bar those made through the Inter-American Court); the status of the military in law; the denial of human rights to ‘terrorists’ and ‘alleged terrorists’; the shameful doctoring of the national curriculum (which absolves the military of everything) and the continued marginalisation of half the country’s population. There is a pressing need for government to reach out to Quechua speakers and reassure them with action that its concept of Peru extends further than the affluent Lima suburb of Miraflores.

Backsliding in the Andes?

The issue of immunity is at the heart of the matter, so too is how a reformed state can make amends without sowing a similar conflation of horrors which will arise at some point in the future. It’s a fascinating study on the role of a truth commission and transitional justice in trying to shape a post-terror, post-abuse framework which will do something to ameliorate those failures which gave rise to both.

Root’s treatment of the evidence, the process and the results is fair and deft.

Transitional Justice in Peru is published by Palgrave Macmillan. You can buy the book from Amazon and other booksellers.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.