An Inventory of My Life: PowerPaola on ‘Virus Tropical’ and Turning a Graphic Novel into a Film

25 August, 2020[Lee en español aquí]

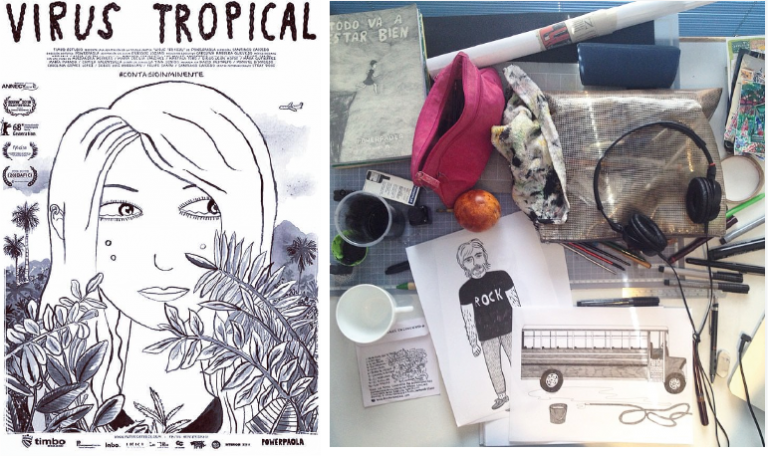

PowerPaola is a Quito-born-Cali-raised artist, cartoonist, and writer. Her hit autobiographical graphic novel, Virus Tropical (2011), was made into an animated film in 2017. The film, directed by Santiago Caicedo, is an original, visually-arresting coming-of-age story and, unsurprisingly, it snatched up several awards at the Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Cinema and an Audience Award at South by Southwest. You can see our recent review of the film here.

We reached out to PowerPaola to hear more about the success of her first film, the task of adapting a graphic novel to the big screen, and the comics and graphic novels that most inspire her.

I know you’ve drawn on your own life experiences in a few of your other books and pieces, but what was it like to look back at your childhood specifically, and to turn it into art or a story?

I think that childhood is something we all return to, in some form or another. It’s the place where we learned everything, where we came to know the world for the first time; you revisit it to understand where you came from, to understand your connections, attachments, and emotional patterns.

I don’t know if I always expected it, but it was a story my sister and I would return to often, to better understand who we were, I suppose. We’d pretend that our family’s story could be a movie and that Almodóvar could be the director, with his aesthetic combined with an Ecuadorian and Colombian aesthetic.

Which graphic novels or comics influenced and inspired you when you were starting out as an artist, and what drew you to visual narratives as a medium?

I was always drawn to unconventional stories, where the art style communicates something new, something specific and unique to that style of drawing. Lots of comics inspired me, particularly lots by women.

The magazine Aline Kominsky and Diane Noomin used to publish, Twisted Sisters; New York Diary by Julie Doucet – actually, there’s a sequence of panels in Virus Tropical that are a nod to one of her strips; Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, of course; Mark Beyer’s comics. When I was a kid, though, I read the comic strips that came in the paper. Calvin and Hobbes was my favorite. The real comic book fan was my sister, Patty, however. She spent all day reading. She had boxes full of comic books.

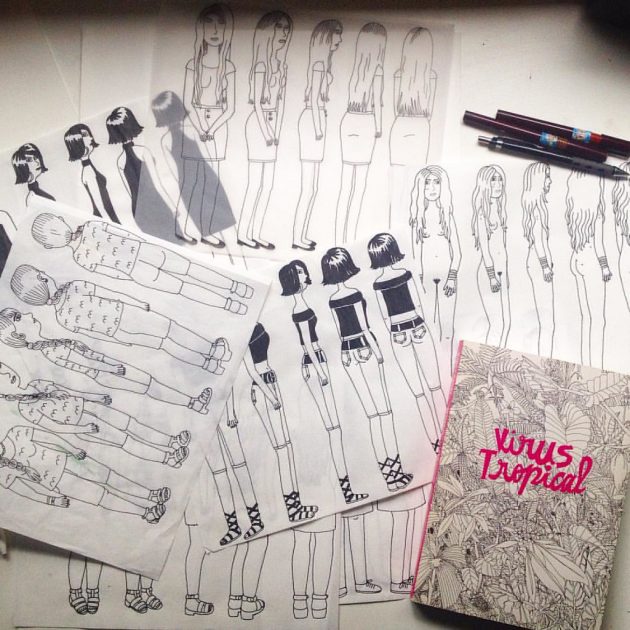

I read that you had to draw an additional 5,000 drawings for the making of the movie, and I’m curious about the work that goes into taking art that is 2-D and static to create something more 3-D and dynamic.

They weren’t additional drawings: I drew everything all over again, because we wanted [the film] to be its own separate thing. Besides, it’s a different process. Everything needs to be drawn on its own, like an inventory of my life. I drew all the characters, for example, and then the animators vectorised them and transformed them. I drew mountains, trees, extras, floors, architecture, objects, all kinds of things.

It was all new. I’d made a short film with Santiago Caicedo before that where we used the same team and the same technique, but this was a huge undertaking.

Generally in my line of work I decide everything on my own. I’m my own secretary, accountant, and community manager, and cartoonist. For the film I only had to draw, draw, and draw. It was five years’ worth of work.

While watching the film, I was struck by how rich and detailed the frames were, and how energetic the animation style was. I felt it took the original aesthetic of the novel to another level. What other opportunities did a film format present that perhaps a sketchbook does not?

I really loved working as a part of a team, working on a different scale. Getting to know people, sharing and enjoying this great challenge together, it was like a game of much greater proportions.

Were there any little details that you were especially fond of including? I enjoyed trying to see what books your family members had on their shelves, for instance…

I really like my house’s bookcases. You can see all the references from my childhood on display there, which I sort of see reflected in my style. I really enjoyed making my Barbie playhouse and a few other things that aren’t there.

There are people in there from the period in which I drew the film. Friends, people who helped finance the movie. I like that, that we did it between a lot of people.

I know your primary role, then, was that of artistic director, but how involved were you in choosing and working with voice actors, or in composing and selecting a soundtrack?

My job was just drawing. The idea and vision for the project was Santiago Caicedo’s, and he was the one who took care of almost everything.

Santiago did the casting in Colombia and Ecuador. It was a big process, plus he recorded background sound clips, too, of birds and everything else from those areas. Enrique Lozano, who’s a playwright, the writer of the script, and my ex-husband, was also involved in that. Diego León Hoyos’s voice was the one that impressed me the most – partly because he is a fantastic actor and partly because that voice is identical to my father’s.

What was it like to work as a part of a team for the making of a film, and particularly for a film about yourself?

From the beginning Santiago wanted to be really respectful of the story and my family. It also worked out perfectly for Enrique Lozano to adapt the book to the screenplay because he captured the essence of the novel and most of all because he had a first-hand familiarity with my background. Because the main team was made up of friends there was a lot of trust that they would do right by the story as much as possible.

Have you been surprised by the reception of the film so far? How has your life changed, if at all, since its release?

The response to the film has been amazing to me. It’s been screened at a lot of festivals, it’s won several awards, and for three years I was constantly traveling alongside the film. I never expected it would be like this. To me it was an amateur project between some friends that turned into something far bigger than we imagined. My life has changed. I was a little shaken up after so much exposure and movement. Now I’m trying to slow down a bit and operate on a smaller scale. With a desire to keep working on different projects. And, well, in this current context, I’m glad in some sense to have eased up a little.

Do you want to make more audiovisual content in the future?

I’d like to, but with the same team and the same freedom. Without that, I’m not interested. It’s far too much work to not be having fun in the process.

What did your family think about their portrayals in the film or book?

They really liked it. It moved something inside them, too.

How have your work style or plans changed as a result of the pandemic? Have you found any inspiration in the isolation?

I’ve finished a couple of books I’d had in the works for nearly four years, and I’ve been working with Barbi Recanati on a book about women in rock. My life hasn’t changed too much. I’ll always be working in isolation or in waiting rooms. I’m realising I already lived in quarantine, a bit.

Which Latin American graphic novel have you enjoyed recently that you can recommend to us?

I don’t know whether to call them graphic novels, that can be a murky term sometimes. I like comics or books that play around with text and images. I enjoyed stuff like: El Gran Espíritu by Tomás Olivos, Squish by Muriel Bellini, Gira de Pizzerías by Camila Torre Notari, and Cotillón by Jazmin Varela.

Virus Tropical is available to watch on MUBI

The Virus Tropical graphic novel can be found here, translated into English by Jamie Richards

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.