Fatherhood, Family and Film-making in ‘The Calm After the Storm’

13 January, 2022

‘Mati accused us of violence in filming the other. He said life had to be lived before being filmed. That didn’t worry Dad because he only did this outside of the home. What he filmed at home was just to save the memories… At first I believed that too.’

Mercedes Gaviria Jaramillo, a film student, sound designer and the daughter of one of Colombia’s best known directors, Victor Gaviria, gently contemplates the ethics of filmmaking and representation in ‘Como el cielo después de llover’ (The Calm After the Storm, 2019).

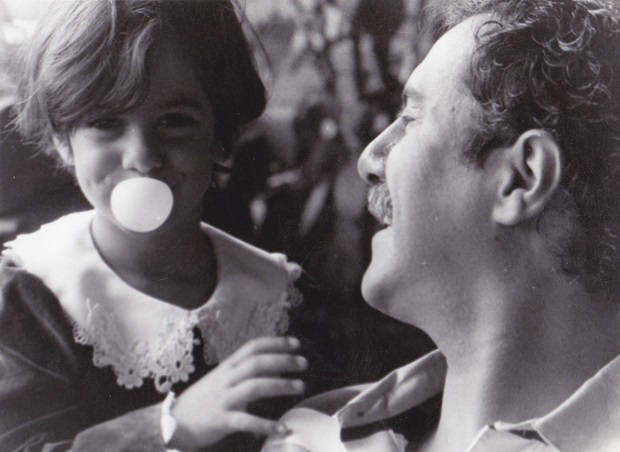

This personal, auteur-essay film laces together four elements: vintage home videos of Mercedes’ childhood; recent intimate family snapshots; behind-the-scenes footage from the set of Victor’s 2016 film ‘La mujer del animal’; and observant, poetic narration.

The central figure of the film is Víctor Gaviria – the acclaimed paisa director known for Colombia’s most famous film, ‘La vendedora de rosas’ (The Rose Seller, 1998) and we get unparalleled access into his home and work environment.

The loose storyline begins when Mercedes agrees after much insistence to return to her native Medellin from Buenos Aires, to assistant direct her father’s latest film ‘La mujer del animal’ about a woman who suffers years of brutal, violent abuse at the hands of her neighbour. But under one condition: that she can film behind the scenes.

As in all of Víctor’s films, the cast is primarily made up of ‘non-actors’, often blurring the lines between documentary and fiction. Avoiding direct critique of her father’s work, Mercedes questions the fundamentals of care on set. She asks her father ‘It’s pretty exaggerated, Dad, have you thought about how you’re going to film those long rape scenes?’. She asks Natalia, who is to play Margarita, how she feels about acting out the scene (afraid, she tells her), and poses the same to Tito, who plays the abuser, ‘El Animal’. He says it will be easy to emulate the character; he knows lots of men like this. The almost all-male crew tower over the two actors, commenting and directing them. Mercedes’ narration highlights “the contradiction of filming a rape scene, being of the privileged gender”, on “a set full of men”.

We could compare Gaviria’s set to that of Michaela Coel’s 2020 series ‘I May Destroy You’, where an Intimacy Coordinator ensured a safe space for the actors so that they could make work about exploitation, loss of respect and abuse of power “without being exploited or abused in the process.” Coel described shooting without an Intimacy Coordinator as messy and embarrassing for the crew, and internally devastating for actors.

All of Gaviria’s films present raw subject matters, looking at the lives of poor and marginalised Colombians: ‘La vendedora de rosas’ framed the lives of children on the streets of a poor neighbourhood in Medellin; ‘Sumas y restas’ (2004) focused on the drug trade; and ‘La mujer del animal’ (2016) gendered domestic violence. We might wonder why Gaviria is the right person to tell these stories.

Mercedes includes a scene of her and her father driving up through Medellin’s comunas, where ‘La mujer del animal’ is to be set, and stopping in on Margarita, whose harrowing past is the basis for the film. Víctor warmly greets her like an old friend, asking her to join them on set. ‘What, all that sadness and suffering?’ she asks, bemused. ‘We’re just playing up there’, he replies, jovial. Margarita’s response is firm: ‘You can’t play with stories like that’.

Some describe Gaviria’s films and process as an “absolute dedication to the truth”, calling him “an anthropologist, sociologist and psychologist” in relation to his research and productions presenting difficult realities from the peripheries of Colombia. For others, it may seem gratuitous, appropriating, patriarchal. Despite ’the international success of ‘The Rose Seller’, which went to Cannes Film Festival in 1998 and was selected as the Colombian entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars, many of the young cast who inspired and acted in the story have since died, gone to prison or continued to suffer from poverty.

Critics of ‘The Rose Seller’ argue it is part of the ‘Pornomiseria‘ (poverty porn’) genre: films made for the international film festival circuit, depicting troubled lives in impoverished neighbourhoods in order to affirm Western stereotypes about the ‘Third World’ and feed into a First-World appetite for misery in order to win accolades. Luis Ospina, the Caliwood director who coined the term in a manifesto against pornomiséria, is credited with special thanks at the end of Mercedes’ film (alongside Pacific-coast director Jhonny Hendrix and others).

In response to the pornomiseria trend, Ospina co-created the mockumentary ‘Agarrando pueblo’ (The Vampires of Poverty, 1977) which portrayed a director desperate to capture sensationalist footage of the slums, staging misery for the cameras. While ‘Como el cielo después de llover’ may not be as direct as Ospina’s film, it does something to balance the scales.

The subtle power of ‘Como el cielo después de llover’ is that as auteur, Mercedes reclaims her father’s footage, gaining control over hers and others’ representation and encouraging a reassessment of the ‘reductive past’ framed by her father.

Although the home videos frame Mercedes as a child, as the filmmaker, she turns our attention towards the man behind the camera: compulsive, intrusive, patriarchal, affectionate. We see a distinctly macho, stubborn side to Gaviria’s character and the links are drawn between patriarchy in the home and on set. Mercedes’ narration guides us to gently question the effects of being filmed, and to ask what is left out of the frame. She tries to understand her mother’s experiences as a newlywed, alone, while Víctor made ‘The Rose Seller’.

Yet ‘Como el cielo después de llover’ muses on the ethics of representation without pointing fingers. Observations are tied up with the nostalgia of returning home, the hope for a career that values women, and a daughter’s admiration and affection for her father, whose profession she’s followed.

The film opens and closes with a simple, rudimentary close-up of a plant which ‘falls asleep’ – its spines curling inwards – when a finger touches it. Mercedes, without scathing critiques or dramatic revelations but through touching on her father’s work, the industry, and her past, puts her daddy issues to rest and encourages the audience to sensitively, maturely question patriarchy in the film industry and the home.

Those interested in film, fatherhood, or Gaviria himself, will enjoy The Calm After the Storm for its observational, informed style and unrivalled intimacy with one of Colombia’s best known filmmakers.

The Calm After The Storm (Como el cielo después de llover) was recently named as Best Documentary – together with Natalia Gayaralde’s Splinters (Esquirlas) – at the Cinema Tropical Awards, and is available to view in the US and Canada via OVID.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.