Fear, Intimidation and Brutality: The Role of Music and Culture Amid Colombian State Terror

18 May, 2021It was only for a fleeting 72 hours or so, but if you looked hard enough in the international headlines just over a week ago, you may have noticed an increased focus on Colombia.

After international headlines fleetingly expressed grave concern at the brutal oppression of nationwide protests, before retreating back into a deafening silence which belies the insurmountable wave of resistance taking place nationwide, the protests have multiplied each day over the last 2-3 weeks.

Deadly repressions from security forces have left as many as 47 people killed, over 1000 people injured, scores of people missing, and dozens reporting sexual abuses, all at the hands of Colombian security forces. Meanwhile, negotiations between the government and the national committee representing the strikes are at a standstill.

Despite much of the disdain around the current climate, which places an aggrieved society in deeply rooted opposition to previous events leading up to the current situation, the latest round of strikes in Colombia were initially sparked by a rejection of tax reforms aimed at working people.

In an already desolate economy which has born the brunt of the Coronavirus pandemic and shrunken by around 7%, poverty rates within the country have risen by 43%, and youth unemployment in some parts of the capital is as high as 50%. If the tax reforms might have already seemed harsh, it is when they are cast against increasing defence budgets, much of which are being actively used to suppress its own citizens, that in this instance the proposed policies quite literally add injury to insult.

Yet the now-scrapped economic overhaul merely represents the tip of the of a gargantuan iceberg, in a deeply divided society that is beleaguered by increasing violence and state abuses over the last few years. The ruling party, whom had previously campaigned against the peace deal between the Colombian government and armed rebel forces in 2016, have been widely criticised for their non-fulfilment of the peace accords on account of a failure to address a surge in murders of social and community leaders since its signing.

The first mass mobilisations against the current regime in 2019 petered out at the start of 2020, but were shortly followed by a surge in massacres throughout rural areas a few months later and further compounded by a series of chilling September nights, during which at least 10 people where shot dead when police embarked on a seemingly indiscriminate shooting spree in the capital, Bogotá. As police drew their guns once more on the 28th of April this year to quell protesters, leaving amongst the dead 17 year old Marcelo Agredo, it was but the spark to an already overexposed touchpaper long-waiting to be ignited.

Musician and anthropologist, Alejandro Cifuentes, who also drums with groups including Bandejas Espaciales, Fanstasma and Dorado Kandua and was recently involved in the British Council’s Mestizo project expresses: “After many years of hard oppression, people can’t stand anymore. The trigger was the new economic policy, but behind that there are so many reasons to stand up against this government. The profound lack of leadership of (president [Ivan]) Duque, the failure in the way they have run the country during this pandemic and the fact that they didn’t assume their commitment with the peace agreement, just to name a few points, has driven popular discontent very far. On the street, above all there are young people, hopeless students, unemployed young people who are tired of being lied to systematically. These demonstrations show us structural problems that have plagued the nation for decades: racism, classism, social inequality, and so on”.

In the conflict that has re-emerged in Colombia over the last three or so years, it is indeed cultural diversity, represented in its various forms, that has been under attack. Numerous community and social leaders have been assassinated, many from Afro-descendent and Indigenous backgrounds and together with those defending victims and workers interests, they have suffered the most. Meanwhile cultural outlets, providing a platform for freedom of expression amongst citizens, have been targeted through orchestrated campaigns of intimidation and fear.

To understand the full picture of the current Colombian situation, we must go back in time to understand how events have unfolded in the context of the current standoff.

Confusion, Chaos and State Intimidation

On the back of a powerful display of discontent in the national strikes of autumn 2019, over November 21st and 22nd, residents first of Cali, and then Bogotá respectively, lived out two consecutive nights of terror.

Placed under curfew, they watched anxiously as gangs of purported vandals attempted to enter gated apartment blocks. From inside their houses, citizens hid from what they believed to be people trying to break in from the outside. Although, it wasn’t all it may have seemed at first sight.

A confused, outgoing and generally unpopular Bogotá mayor with little left to lose, Enrique Peñalosa took to the airwaves. Garnering a rare sense of commonality with the capital’s disillusioned citizens he planted the first seeds of suspicion, “this is not something real, this is something orchestrated. An orchestrated campaign” he explained, alluding to actors beyond his reach or control. Alongside him was a chief of police, who appeared to many as trying to contain a straight face.

A central point worth noting at this early stage is that Colombia’s police force is the only one of any democracy worldwide not considered a civil branch. That is to say, acting under the order of the defence ministry, it is militarised. Operating under a national directive without localised units, it acts under the command of the minister of defence, who in between 2019 and 2020 was headed up by Carlos Holmes Trujillo. After passing away due to COVID-19, Holmes Trujillo was replaced by Diego Molano, both close confidants of ex-Colombian president Álvaro Uribe, in a government led by Uribe’s political protégé, Ivan Duque.

Other videos later released from the two nights of terror in Bogotá and Cali, put it much more starkly for citizens. It was indeed an orchestrated campaign, but not as had first appeared. Evidence emerged of police coordinating and transporting the purported criminals, carrying out acts of vandalism and terrorising citizens cowered in their houses. The game, for many Colombians, was up. “Todo fue un montaje del estado” or “it was all a state set up” was the trend on Twitter.

As the real and obtuse intertwined, the seeds of confusion and chaos had been sown. In what has now become an ongoing strategy amidst the unrest of recent years, policemen appeared to routinely dress up in civilian clothes, creating acts of violence and vandalism so as to discredit any legitimacy of protesters and create confusion and fear amongst citizens.

The campaign of fear during those November nights, however, had the opposite effect to those they sought to provoke, with many citizens finding themselves all the more reinvigorated and resolute to protest than before.

Marches continued, and a week later in Bogotá city centre, 19 year-old student Dilan Cruz was shot dead by a police ballistic (a bean bag full of ball bearings) aimed at his head from some 30 metres away. A ‘stray projectile’ claimed the authorities. Meanwhile, Colombia’s fear turned to anguish. The example, the most spotlighted from the ongoing protests at the back end of 2019, did not stand alone, with two other young protesters killed in the same period.

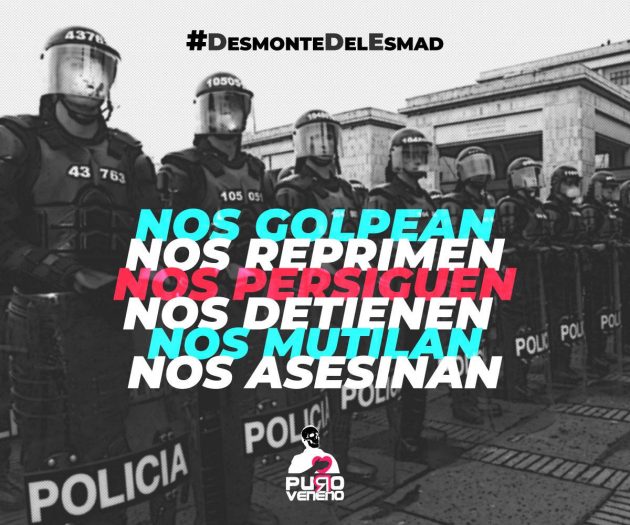

In September 2020, during a case which analysed acts from the last decade on the part of the national police’s anti-disturbance unit, ESMAD, Colombia’s supreme court ruled that the “disproportionate” and “excessive force” of the unit has constituted a “constant aggression” acting in an “uncontrolled and aggressive fashion.” The unit continues to operate and a large number of those killed in recent manifestations have been attributed to ESMAD. Many in the current climate are calling for the dismantlement of the unit, alongside a complete overhaul of the police structure.

An Unrepentant Ex-President and an Upsurge in Violence

Despite a fleeting de-escalation in violence on the capital’s streets during the immediate aftermath of Dilan Cruz’s assassination, the following 10 months were amongst the most violent in Colombia’s recent history. Human rights abuses rocketed. The systematic assassinations of social leaders now stand at over 1,000 since the signing of the 2016 peace accords. UNHCR recorded 66 massacres involving 255 people, as well as the assassinations of 120 human rights leaders in the country during 2020 alone. They also registered 244 killings of ex-FARC members who had laid down their arms in 2016.

It’s essential to understand the role of the ex-Colombian president, Álvaro Uribe, in the current unrest.

A prominent voice in the public political sphere and a key proponent in the rejection of the peace process in Colombia, many suspect him of continuing to pull the strings in the country. Linked to the formation of paramilitary groups through informant networks, retrospective testimonies, and increasing evidence against him including recently released Pentagon documents from the time of his presidency, Uribe appears to have gained favour with the US on account of his heavy handedness against leftist guerrilla units. Often though, his clampdowns in the early part of the decade have taken place at the price of numerous human rights abuses.

“A close friend of Pablo Escobar Gaviria”, reported NSA cables from 1991. 13 years later, during the years of his presidency in 2004, according to cables declassified in September 2020, it has been revealed that the United States continued to link Uribe to paramilitary networks while also collaborating with him. “Uribe almost certainly had dealings with paramilitaries”, said US Department of Defence’s Assistant Secretary for International Security Affairs when confiding to his boss at the time, Donald Rumsfeld

A scenario of chaos, war and fear have fared well with his desired conditions and throughout August and September, following his house arrest on accusations of manipulating witnesses, 2020’s violence began to escalate out of control.

Prominent Bogotá musician Pedro Ojeda commenting last September, said “He [Uribe] seems to be continuing to command from ‘behind the scenes’, inciting repressive and insane policies, such as bombings of territories, from his Twitter account.”

By September, following an upsurge of massacres in rural areas, when police killed Bogotá resident, Javier Ordóñez, by persistently tasering him after he was detained for drinking in the street, the capital city exploded in a pent up rage. An outpouring of sadness soon manifested in anger; citizens took to the streets in protest. Over the following nights between the 8th and 10th of September, over ten people were shot dead and hundreds injured by police who opened fire at will against unarmed citizens. Videos circulated of brutal tortures. Women denounced sexual abuses and rapes that took place in local police stations during the aftermath.

The massacres that had been plighting the rest of the country throughout 2020 arrived to the capital’s streets. It was Bogotá’s bloodiest fall out in recent history, surpassing the Palace of Justice siege by M-19 guerrillas in 1985.

“What has happened is an authentic massacre against the youth of our city,” publicly proclaimed Bogotá’s current mayor Claudia Lopez. She had apparently told the police to not open fire in repeated statements that again cast doubt on the relationship between senior regional authorities and state controlled police forces operating under the order of the Ministry of Defence.

Nevertheless, the mayor’s authenticity has also been called into question during recent events. Despite promising ESMAD would not return to patrol protests in January 2020, the anti-disturbance unit’s presence has since increased along with its artillery, which has reigned terror upon Colombian citizens in the recent round of protests. Moreover, despite calling for an end to the recent violence, and repeatedly positioning herself in opposition to the government, communications recently published by hacktivists Anonymous, reveal the mayor made an under the table deal with president Iván Duque to militarise the streets of Bogotá at the start of May, shortly after rejecting the notion. Anonymous have been highly active in the country since last week, taking down the national military and police pages as well as revealing how internet blackouts coincided with outbursts of police violence in the city of Cali.

The gateway to the Colombia’s Pacific region, and a melting pot of cultures divided upon lines of inequality and race, Cali has been a flashpoint of much of the recent violence. In similar scenes to those that rocked Bogotá last September, security forces have routinely entered working class neighbourhoods throughout the current unrest, again shooting without restraint. In one neighbourhood, residents filmed from apartment windows as they were shot at in their homes.

With violence spiralling out of control, the government narrative of it over the last few years has also followed an alarming development. After an initial attempt to appease concerns on the basis of ‘Manzanas Podridas’ or ‘a few bad apples’, and those killed being done so at the hands of stray projectiles so as to pass off past criticism, rebuttals of state abuses took on a much more unrepentant tone last September.

“Let’s be clear; the national police do not need permission to open fire”, nonchalantly dismissed the chief of police during 2020’s shooting frenzy. In 2021 this has evolved into something much more sinister still.

“It is a fascist attitude closely connected [to] Centro Democrático [and] its leader Álvaro Uribe” said Pedro Ojeda, speaking last September.

Amidst the latest violence, ex-president Uribe has indeed been pedalling far-right ideology, recently tweeting as to how Colombia was required to resit the ‘dissipated molecular revolution’. The theory, originally coined by French psychoanalyst Felix Guattari, was later reinterpreted and mutated by its key contemporary proponent in Latin America, Alexis Lopez. The Chilean founder of National Socialist group, Nueva Patria, has in the past also been photographed bearing swastikas, organised the Santiago National Socialist congress of 2000 (later cancelled on account of the danger it posed) and has on two occasions in recent years been invited to Colombia’s military colleges to talk directly about the proclaimed ‘dissipated molecular revolution’. His Twitter biography calls for loyalty to the homeland or chaos.

With the ex-president seemingly calling orders from his Twitter account, president Duque’s continued failure to recognise the disproportionate use of violence, instead trivialising the severity of acts down to vandalism, and his former chief of staff turned defence minister Diego Molano denouncing protesters as ‘terrorist vandals’, it is vital to understand Sanchez’s definition of the ‘dissipated molecular revolution’ in relation to the apparent government gaslighting of current unrest.

Founded upon the notion that small actions of resistance, as they escalate become massive, filling spaces, and end up unleashing great revolutions, it is the rhetoric of Lopez and most recently, Uribe, Duque and Molano, that such movements should be repressed in full force and from the ground up. The ideology that has built, not just in recent discourse from the ex-president, but also over time, includes the police scare-tactics of 2019 in Bogotá and Cali. This rhetoric converts protesters and their forms of expression into internal enemies, thus under its homiletics justifying state abuses against them.

It is from this foundation upon which much of the right to protest is becoming increasingly delegitimised in Colombia. “National government authorities have publicly stated that the demonstrations embody ‘terrorist’ purposes and that, for this reason, excessive use of force against the population is justified. The stigmatisation of social protest only generates repression and human rights violations, as well as an atmosphere of distrust in the authorities that does not lead to the genuine establishment of channels of dialogue”, denounced Amnesty International of the latest acts.

This is also a vital background for understanding attacks on cultural outlets, spaces and manifestations that bring together diverse members of society, considered both a vital point of resistance and as such, in the eyes of the current government, a legitimate target of its attacks. All forms of cultural expression, from music through arts, community and youth groups are providing a much needed dialogue and fabric of reconciliation amongst the nation’s citizens, whilst offering unity and social cohesion that the state has neglected to provide.

State Repression of Cultural Outlets

On November 19th, 2019, two days before the first national strikes, national police entered and raided dozens of properties, belonging to artists and members of cultural collectives across Colombia, in Bogotá, Cali and Medellín.

“We are culture, and you treat us like we are terrorists”, one man from popular alternative media outlet, Cartel Urbano, decries in one of the dawn raids at the order of the national prosecutor.

“This morning we were victims of persecution by the Sijín (one of Colombia’s highest police authorities), armed with intimidation and a brief search warrant. Instead of finding explosives and terrorist pamphlets, they took evidence of a sample from ‘#CreadoresCriollos’, which expressed our nonconformity through art and culture” the group said in a statement at the time.

Puro Veneno, another collective whose art often directly addresses former president Uribe and his party, were also raided, stating that, “All the orders were legal, however, in several of the cases that we are aware of, search warrants were carried out with irregularities. Such as, attempts by some of the police to enter without the owners of the houses realising, with bags full of objects that we are not aware of.”

It is a strategy that extends throughout the creative sector and takes place at every level. From the financial starvation of alternative cultural industries, through dawn raids and heavy handed attacks on grass roots manifestations. ESMAD have also arrived at gatherings from musical collectives throughout the last few years’ protests, in line with the state’s campaign of intimidation to undermine creative outlets.

In one such example, after locals of Teusaquillo, a traditional Bogotá neighbourhood where many artists converge, opted to turn a burnt out police station from last September’s protests into a library for the people, scenes were at at first heart-warming. People of all ages came and left literature, while artists painted the streets with memorials. Music was on hand at the courtesy of an impromptu set from Frente Cumbiero’s Mario Galeano, who played vinyl records. An array of sub-cultures could be found, all offering a voice to the frustrations. Lurking in the shadow’s the whole time though were ESMAD. As the peaceful manifestation grew in number, the anti-disturbance unit eventually fired off a cocktail of tear gas and stun grenades at the gathering in order to break it up.

The same neighbourhood became a focal point throughout September, as it had been for much of November and December’s protests in 2019. Gatherings were peaceful but vocal. Shortly after the previous attacks, at the end of September 2020, a group of musicians formed an impromptu bullerengue circle; the military, apparently on a routine operation in the area, circled in. After some negotiations with city officials they proceeded to leave, though not without their presence being made known in a chain of events that comprise a routine strategy of intimidation focussed on cultural platforms. Military intervention of artistic expression has carried through to the latest protests, where just over a week ago they were deployed to paint over highly critical murals in Medellín and Cúcuta.

“Now it becomes more difficult, because you see, the government goes around profiling the people and cultures who are protesting through music. They see you so much, and so they persecute you. They block your channels, they block the means through which you speak and they become more and more closed”, says Chocó-born rapper, Alexis Play.

“It sounds like a cliché, but it must be repeated,” offers Bogotá DJ and promoter of over ten years, Chiflamicas, “music is our weapon.”

Music and culture continue to be resolute and resilient. There are number of heterogeneous voices in Colombia’s struggles, but Pedro Ojeda suggests that artists are centred on a few core principles that were being fought for even prior to the 2021 tax reforms:

“In general, amongst musicians and artists we have some clear meeting points, that are: the defence of the peace process between the FARC guerrillas and the government and the defence of the Special Jurisdiction for La Paz (JEP), which must welcome all the protagonists of our recent armed conflict, both the guerrillas and the paramilitary armies (AUC), members of the public force, army, politicians, businessmen, etc., in order to guarantee processes of truth, justice and non-repetition of the armed conflict. Next, the defence of the paramos, rivers and the fight for the environment and against the interests of some mega-mining projects of foreign multinationals that seek to exploit territories that are natural reserves. Third, the fight for civil liberties and freedom of expression. Finally, the fight for robust cultural policies that strengthen the social fabric in the territories.”

Alejandro Cifuentes adds, “The role of music is very important in a country where [there are] few spaces to express our emotions related to the armed conflict. Music shows these feelings. These feelings of frustration, anger and impotence of a long war, which despite the agreements made, continues to be perpetrated in the countryside and now this has broken out in the main cities of Colombia. Music serves as a meeting point for the country’s diversity, where new positions and reflections are harmonised in order to denounce inequalities”.

Yet, all the while, while on the one hand being censored when it makes critical statements, culture continues to be exploited by the government in the form of culture-washing; celebrating cultural touch points as and when it aligns with their agenda, manipulating them to create favourable associations with their image.

The most recent example of this came last weekend as President Duque held meetings with religious leaders and victims of Colombia’s ongoing conflict, in the exhibition space of prominent artist Doris Salcedo’s Fragmentos installation. For her installation, Salcedo, in collaboration with hundreds of female victims who had been sexually assaulted in the the armed conflict, melted down surrendered arms from FARC ex-combatants into 1,300 tiles which aimed to revisit narratives glorifying conflict.

Using the space to dismiss current protests as the “incitement of violence, hate, discord, and the destruction of society“, the president continued to undermine the legitimacy of the millions marching in opposition to his government. Notably the governmental committee, during their highly publicised meeting, covered up works by Belgian artist Francis Alÿs, through which the artist documented the social collapse and absence of sense amidst the backdrop of conflict. Doris Salcedo, speaking to arts e-zine Hyperallergic, criticised the move, stating the government had “abusively used [the space], breaking all the international norms of conservation and copyright”. She further decried, “this unconsented event happened in the middle of a terrible civil unrest that has left more than 30 citizens killed, dozens disappeared, hundreds injured, and cases of sexual abuse.”

Artistic Voices Rise Up

It’s no understatement, then, to say that culture has played a central role in bringing together a collective output for expression. The latest protests have seen a vast array of artistic expression in their wake. Another worthy access point for such works can be found on Sello In-Correcto’s “Estamos Por La Utopia”, a collection of resistance-themed tracks it labels “Sounds of Emergency against a Colombian police state”, where other artists have also used their platform in light of recent happenings in Colombia.

Actors from across the creative scene have banded together in recent years from a number of fronts. Pacifista are one such collective of artistic voices and peace advocates who produce content focussed on the construction of peace in Colombia. Last September while protests took place in various parts of the city, in an event arranged by a number of artistic collectives and attended by members of the public in Bogotá’s national park, people gathered to reject the violence they have been living through. They painted in giant letters a mural upon the floor, “We resist your bullets, without forgetting them”, inviting members of the public to seek reconciliation through sharing stories of police oppression.

“We tried dialogue with them, and it didn’t exist. Now it’s between us, between the community. Through art we unite, we organise, reconcile and raise our voices. These works, they unite us all,” bellowed out one of the voices gravitating around the axis point of The Gran Latido Sound System, which provided the beat to the day’s events.

“They took me, beat me, extorted me, mistreated me and tried to hand me over to the paramilitaries,” said another of the young speakers recounting experiences from the Colombian Pacific.

Homages were laid out to victims, as El Teatro Popular performed, “Sin Nombres, Pero Con Victimas” (“Nameless, But With Victims”). At the end of which a pile of limp actors formed a mountain of corpses, representing some of those taken in recent months. A blood-hungry crow smeared himself and a Colombian flag in a bloodthirsty frenzy. These are emotive displays. Brutal in their directness at times. Honest.

Chiflamicas, who has been uniting with Suena, a musicians group organised around providing the beats and sounds to the protests, reflects on how creative voices are collaborating to provide an outlet for frustration. “Our immediate goals are to present a voice against the massacres and growing murders of social leaders, and we aim to support every cause that pursues the awakening of Colombian society and the recovery of a real democratic country free of the dark shadow of the narco-paramilitary rule. We want to walk beside the silenced voices.”

“I can only speak for myself, but those who have gathered to make their art a vehicle for protest and freedom are rallied upon denouncing the cruel and dark time we are living. What looks so imminent and powerful is nothing but the outcome of decades of social injustice. We stand together and claim for the implementation of the Peace Treaty and eradication of the corruption that runs in the veins of every institution of this country.”

This artistic amplification on the rejection of violence during the manifestations, has seen artists and musicians forming La Segunda Linea (The Second Line), who stand directly behind leaders of the mass marches in the city’s capital.

Alejandro Cifuentes, who has also been performing in La Segunda Linea, explains, “A friend from la Segunda linea says [it exists] “To point out what is alive and what feeds us from this civil struggle. Create a renewed discourse tailored to this moment and this territory. The power of art in the processes of social transformation is much greater than society imagines”. Everyone in La Segunda Linea has a high concern for what is happening in Colombia. We maintain a critical posture through the music and we’re persevering, being as consistent as we can during the demonstrations. Our voices can’t be shot down.”

Quién Los Mató?

It’s necessary at this point to zoom out again. This time geographically. Moving away from the current abuses within the cities, which have garnered widespread recent attention, to understand a little about what has been happening in Colombia’s regions. Here, rampant violence has been escalating and massacres, largely of younger people and minority groups, have been spiralling out of control. Human Rights Watch found that in at least 11 departments paramilitary orders had been received during 2020’s quarantines, in some localities quarantine measures were indeed actively enforced by local armed groups themselves.

The increasing network of paramilitary units and unknown armed groups is, apparently, of little coincidence. Colombian based human rights NGO, Somos Defensores, state in one of their latest reports that, “one of the most worrying strategies of the security and defence of the Duque government is the so-called ‘network of civic participation’, that starts from a premise: security is everyone’s business.” It goes on to explain how communities are essentially free to organise amongst themselves, provided they align with military and police objectives: “this network doesn’t need to remind us of the experience of donor networks and informants under the mandate of Alvaro Uribe,” it states.

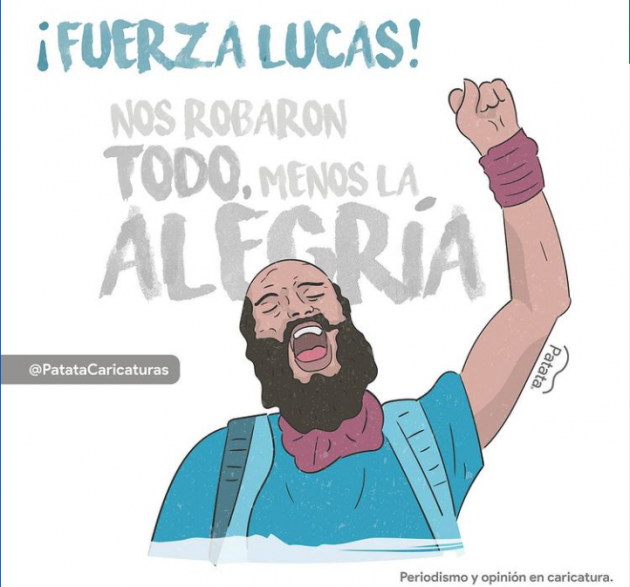

The direct comparisons between the links connecting top Colombian government officials and the formation of paramilitary networks are not to be taken lightly, and were again brought to the fore 10 days ago in the city of Pereira. In a rhetoric unequivocally aligned to principles of Colombian paramilitarism, which has persisted on an underground level after being given license to thrive during the Uribe government, the city’s mayor declared, “We want to call out all of the groups in the city and all members of private security to form a common front alongside the army and the police”. That night, one of Pereira’s prominent faces of the protests, student leader Lucas Villas, who had been filmed protesting peacefully, dancing, and even offering security forces his hand to shake in the afternoon was approached by an unmarked 4×4 and eventually died after sustaining eight gunshot wounds.

“Statements by local authorities calling for civilians to take up arms against demonstrators are alarming and appear to justify the use of paramilitary strategies. This not only violates human rights standards but is an affront to all victims of paramilitary groups in a country that has the longest running internal armed conflict on the continent”, denounced Amnesty International last week.

The rise in massacres in Colombia close to doubled from 36 in 2019 to 66 in 2020. These alone have accounted for 267 murders. In addition, 320 social leaders and defenders of human rights, along with 12 of their family members and 64 demobilised ex-combatants of the FARC who had signed the 2016 peace accords, were murdered in 2020 alone according to human rights group Indepaz; 386 people in total.

Far more often than not though, perpetrators are not brought to justice. According to figures from Somos Defensores, close to 50% of registered acts of violence have been committed by paramilitaries, and close to third of them by unknown actors. Between them, paramilitary groups and unknown actors account for some 80% of all assassinations.

“These acts of violence that are intensifying, are happening apparently in a mysterious way and the government does not provide effective solutions. There is no one captured. Nothing happens. That is on top of the situations that always happen when it has to do with the places on the periphery of the country. So, well, it has been a panorama between despair, fear and misery and hopelessness about the situation”, Alexis Play told us at the end of last year.

“And now, when the police are abusing people; killing people with ammunition paid for by the state, because it is a state entity, well then the state is paying for a group that is also violating us. So one is left in the middle of questioning who really is and who is not violent. That is, who to look at. We remain in the confusion of who is really responsible for everything. If it is the government that is killing programs of people who are against it or really if it is other groups. It is something thing that really confuses everyone.”

In the solemnly titled “Quién Los Mató?” (“Who Killed Them?”), released last September, a collective of Pacific Coast musicians that included Alexis Play, Nidia Góngora, Hendrix and Junior Jein channelled this confusion.

“This is the way we can make a complaint and have everyone look at us. Perhaps if a song like this does not happen, the theme passes, already unnoticed,” Play said, speaking last October. “Now already we might no longer be talking about the subject, and the subject would be in other parts. But it continues to be repeated, there have been more atrocities after that.” At the time he was referring to the massacre of five youths in Llano Verde, Cali, but in the context of recent events this sentiment has multiplied.

Touching on the now recurrent narrative which delegitimises victims of violence in Colombia, he continues: “when the deaths and murders of these 5 boys happened here in Llano Verde, in Cali, the first comments that came to light is that these boys were criminals. They were thieves. That at least they belonged to gangs; there [is] always a justification.”

“Colombia is in a time of mental illness where people justify deaths. So if they murder the thief it is a good death, if they murder the poor it is a good death, ahhh, but if they murder the doctor, the lawyer it is a bad death. If they murder a black guy, OK, Indigenous, no problem. Hey but if they murder the white, mestizo ahiiii, you have to go out into the streets. So it is a question that is not current, that is not new, it is something that happens and continues to happen over time.”

While protests have recently shaken Colombia’s cities, it is a story of ongoing violence that has been tormenting much of Colombia’s territories, including the Pacific region, over the long term without real media spotlight even from within the country. Alexis Play adds, “it is an issue that is global, but in countries like Colombia it still lives. It is an issue that has to do with racism and exclusion, which has a lot to do with classism. The television channels and the news all are still on the side of the state. They prefer to cover up the reality of what is happening, to perhaps give an image or sense of tranquillity, of a quiet country where things do not happen, but everything is happening behind the scenes.”

Whilst there is still little light being shed by official sources on who killed them, there is increasing data on who is being killed. According to Somos Defensores’ recent report into the assassinations of Social Community Leaders, one in three of Colombia’s assassinations registered in recent years were Indigenous leaders; community leaders and human rights defenders comprised almost 40% of overall assassinations; while farmer’s leaders and Afro-descendent leaders account for around 10% of the overall total. It’s culture and diversity at its very root, which is on the front line in Colombia’s territories. That is where people are being murdered.

Quién Los Financió?

Despite The White House expressing their concern over the situation last week many feel that the current US administration have still not acted sufficiently in applying international pressure on the current government. Major questions also remain of preceding US governments as to the financing of a regime led by a man who is now revealed to have long been on their radar.

In the current climate, however, the most pressing questions are around the increasing amounts of money being thrust into the conflict. In spite of the 2016 peace accords, Colombia has spent over $10 billion USD a year on war since 2017 and in more recent years the defence budget has come out at $10.5 billion according to the US Department of Commerce. Of that, according to data shared by the head of the Washington Office on Latin America, some $270 million was attributed from US aid programmes to the Colombian National Police in 2020 alone. While US economic aid for development programmes to Colombia has been cut by nearly 50%, it’s financing of the military in the same period doubled.

Furthermore, there are also questions to be asked of landowners. CINEP, Colombia’s Centre for Investigation and Popular Educational Programmes for Peace, recently revealed to the special courts set up for processing cases related to the peace process, that 95% of Afro-descendent territory in Colombia is still owned by only eight business people. Much of the land appropriation took place following paramilitary incursions in the region through the 90s which caused 93% of families from these regions into displacement.

In much of Chocó, one of the country’s most affected regions by conflict, young people often resist the call of violence through cultural activities. Yet there seems a perpetual vacuum in funding that is causing some young people to fall through the cracks.

“For some young people at this time, there are regions where they do not have many opportunities and that is why they are falling into the trap of war, what war puts there for them in their hand to solve the day-to-day at home,” says Alexis Play

“Looking at the positives,” he continues, “there are also a lot of young people who want to take part in cultural activities, who want to make music, do theatre, crafts and undertake these activities. But there are just not enough funds.”

“I have seen many young people from the music side recently recording and making their music, taking advantage of the silence of major music media, [in quarantine] the big labels have not released as much music and so they are taking advantage of that space to release their own, but the resources are still very scarce, those that are invested in this country for culture.”

Culture is under attack from the state both in the capital, and especially in peripheral regions; it is critically underfunded. There is also a growing feeling amongst many artists that it is undervalued by the government and the returns it does generate are neither reinvested nor fairly distributed into the cultural scene.

“The Ministry of Culture is the one with the fewest resources because Colombia invests money in the war all the time,” reflects Alexis Play. “An immense debt is owed to culture. We all know the main engine of Colombia is culture and from there to agriculture and other things, they are the sectors where less is invested; they prefer to import things. More money to spend on war, war and more war. Not in the priority, which is culture.”

For many, when peace was eventually brokered in Colombia in 2016, they had dared to hope that there may be some significant change. Less money on war, and more for society. It’s not played out that way and for all the money spent on conflict, it’s all the more baffling for President Duque’s refusal of its existence. Somos Defensores go as far as to suggest, “Failure to recognise the internal armed conflict is undoubtedly a return to the similar situation in the past, which occurred during the government of Álvaro Uribe Vélez, who refused to acknowledge conflict and State participation.” Something the UN High Commission on Human Rights called to international attention at the time.

This time around, since the 2016 peace deal, there’s been something of an increased international apathy. “I personally do not understand why international media do not put their hand in this. I do not understand why the UN has not come to address the situation, why international control agencies have not come to face the situation” said a bemused Alexis Play. “It’s one thing we don’t understand. I do not know if it is what does not concern them, I do not know if it is that the governments themselves [are] perhaps in silent agreement, I do not know”, he continues like many Colombians, with more questions than answers.

“It is a question (why no one is stepping in) that Colombians ask ourselves, that hurts us every day, because we see that international organizations only appear to give awards, the Nobel of course, that I know”, he continues half sarcastically, in reference to former president Juan Manuel Santos’ 2016 Nobel Peace Prize.

“They do not appear to give order in a situation that is obviously out of control. That is what the quarantine is about, we have only heard of massacre, massacre, massacre. By chance, Álvaro Uribe was taken prisoner [August 2020] and it all increased, coincidentally. So we don’t understand why there is so much silence because, thanks to the networks, everyone denounces and labels them, that is, there is a way of saying that they do not find out. All the time I go in, I see complaints on Twitter, I see labels for the UN, the OAS, all international control bodies, but there aren’t any here.”

Despite the UN subsequently condemning the most recent outbreak of violence, many are still disillusioned at an apparent disparity between diplomatic disaccord and meaningful intercession. “What it wants to say is not ‘condemnation’ but ‘intervention'”, proclaimed one disillusioned protester during last week’s manifestations.

A Country’s Future In The Hands of Its Youth

While raw conflict, the one in which humans lives are being taken, is currently fought in Colombia on the basis of diversity in cultural backgrounds, it’s upon the aesthetic level, where the outlet of cultural expression is taking place, that the state continues to impose a campaign of fear and intimidation. Meanwhile, Colombia’s insistence on hosting the 2021 Copa America has hailed more internal accusations of culture-washing.

While Colombia’s social fabric continues to be under attack, the rich diversity that comprises its territories, together with those voices who amplify the nature of such struggles – champions of diversity and their communities at grassroots levels – are on the front line of a fierce campaign of intimidation and ultimately, repression. As with all smoke and mirror acts throughout history, though, there are many other fronts where Colombia’s conflict is taking place on a relatively softer level, away from the peering eyes of international media.

Unrelenting campaigns of seemingly disparate acts combine to paint a sinister picture of harassment and state intimidation where culture is a key target. No one doubts that funding is absolutely necessary for Colombia, yet at the moment it seems either directed to the wrong places or provided by the wrong sources, if not both. It is not bringing peace to Colombia.

The suffocation of culture in Colombia, meanwhile, does not tend to bode so well as far as historical precursors go, especially under the animosity of the current discourse. Whatever the next step may be, for many Colombians, the concern is the here and now, and it might be time for some real questions to start being asked from outside of the country.

For the domestic society, meanwhile, the outlook remains increasingly bleak, even if the protests continue unwaveringly. With a repeat pattern of events that prompted economic crises in the 1980s and 1990s on the horizon, Colombia finds itself on the brink of financial turmoil; as the US economy grows from strength to strength, an imminent rise in interest rates in the robustly equipped northern half of the continent are expected to be announced next year, to offset the risk of rising inflation. For Colombia this poses the very real likelihood that large amounts of foreign investment capital will flood out of the country overnight, triggering a devastating crash. The country is on the verge on economic desolation, combined with a plethora of socio-cultural grievances and imminent power vacuums to be filled.

It is then left to the country’s underrepresented youth movements to confront the unenviable task of establishing a national dialogue, one that unifies a deeply divided nation amidst an implacable campaign that seeks to enfeeble the authenticity of their current discourses.

“I hope that a dialogue with the protagonists of this Paro Nacional, the young people, will take place very soon”, yearns Alejandro Cifuentes

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.