Brazilian Wax Awards: Album of the Year 2020

21 December, 2020So, here we are. 2020 is, almost, finally over. The less said about this calamitous year, the better; there’ll be no retrospective taking us through its highs and lows – no need for the typical awards ceremony throat-clearing before we jump in to the proceedings. Cutting the pageantry, let’s just be thankful that, for all 2020’s disasters, Brazil has consistently delivered ground- and boundary-breaking music to keep our spirits up. So abundant has brilliant Brazilian music been this year, that I couldn’t manage to narrow the short-list to a round twenty. So, in the spirit of leaving behind that cursed ’20, below are twenty-one albums that have made this year, temporarily, and in their own small way, a little less of a disaster.

21. Bruno Schiavo – A Vida Só Começou (Selo Sesc)

Bruno Schiavo‘s stumbling off-kilter psych is reminiscent of Ana Frango Elétrico‘s tropicália-for-the-twenty-first-century that skyrocketed to vivid heights last year on her euphoric Little Electric Chicken Heart. The similarities are no surprise, really. Schiavo was on songwriting duty for Elétrico’s jubilant single “Tem Certeza?”. And the favour’s returned here, on the twee “Amores Incríveis” – a bubbly acrylic indie romp led by piano stabs towards washed-out “oohs” and “ahhs”. It’s an awful lot of fun – something that A Vida Só Começou is in bucket-fulls. Schiavo’s is the kind of colourful, no-holds-barred indie that finds its inspiration in a version of the sixties which is just one big group hug with guitars and flares and flowers. Throughout, the retromaniac rifles through British Invasion and 1960s West Coast influences: the baggy “Orestes Revisitado” is jangly Beatlemania; “Orégano”, with wall-of-sound “hallelujahs”, sees Schiavo doing his best George Harrison; meanwhile, the following “Zero Paisagem” begins with syrupy Beach Boys harmonies. The album is awash with production quirks that conjure the likes of The Electric Prunes, as well as neo-psych outfits like Pond, and even various Electric Six groups. The one let-up? After a mightily bombastic beginning, A Vida drifts too often into the realm of style over substance. And, as we all know, the substances were quite integral to the sixties.

20. Mais Uma – QUERO QUERO QUERO QUERO (Tratore)

Mais Uma’s QUERO QUERO QUERO QUERO is an intimate record that puts the listener within touching distance of its makers. On the titular opener, every squeak of the violão and each clipped breath of Jasmim Vasques‘ skipping vocals tingle pricked ears. The following “Súbita Alma” is a sotto voce lullaby, delivered in a moonlit murmur. Meanwhile, reverb-heavy vocals on “O Médico ou o Monstro” bewitch, like a shadowy Y La Bamba demo. Each ASMR-provoking composition feels tantalisingly private, as if the listener were to be eavesdropping upon a hushed midnight jam session. And, indeed, each sumptuous piece thrills like a whispered secret. “Fugindo da Canção” is full of swelling close harmonies that highlights the ensembles perfectly blended (if not pitched) voices. But it is “Livros & Abelhas”, with its lush choral introduction and assertive vocals that truly soars. Delivered like a Baroque recitative, Vasques navigates unexpected chord progressions in full stride, leaping with self-assured poise and marking herself out as one of Brazil’s most promising contemporary vocalists. On QUERO QUERO QUERO QUERO, Mais Uma happen upon a sound that is both languid and electrifying, like a yawn that sends shivers down your spine. The four-piece’s shimmering debut is at once pensive and playful; a soundtrack for quiet meditation or lucent somnambulism.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #4

19. Felipe Neiva – tanto. (Cavaca Records)

Appropriately formatted in scruffy lowercase, tanto. – which means “so much.” – is exceedingly DIY (id est, shoddily recorded) maximalist pop. The shuffling drum samples and gain-heavy vocals of “Desire” is a lo-fi fanfare, over which Felipe Neiva yowls: “Inside my mind/ Desire”. And, it’s the track’s eponymous noun that dictates much of the ensuing 40 minutes. Neiva’s sophomore release on Cavaca Records is an unbridled ode to creative impulse, on which desire trumps discipline – often to euphoric results. On the majestic “Tilele” Neiva, immediately out-of-tune, wails with little restraint. Atop choppy guitars and whirring synths, he steers thrummed guitars and tinnitus synths towards an earth-shattering climax, forcing his voice to unhuman limits.“Amor-Vício” is almost as audacious. With synth strings, vocoder vocals and a stuttering sax solo, it’s equally thrilling. But, late on the album, the unrestrained wailing wears thin – particularly on the inane album closer, which prompts the listener to consider tanto.’s alternative translation: “too much”. But, tanto.’s joy is in its excess. As exhilarating as it is out-of-control, Neiva’s endlessly imaginative album is the sound of someone hitting their technical limits, and smashing right on through them, rocket-fuelled by creative horsepower. Though occasionally we might not lift-off with it, when Neiva’s imagination takes hold of the listener, we soar to unbelievable heights.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #4

18. Josyara & Giovani Cidreira – Estreite (Joia Moderna)

Estreite is a shape-shifting album. In liquid form, it slips in the gaps between various styles – lo-fi r&b, electroacoustic soundscapes, brooding MPB and shuffling IDM. Rarely settling in one groove for more than a minute, each composition’s fascinating, polymorphous arc can be put down to Junix 11‘s sublime production. A sound artist and collaborator with the likes of BaianaSystem, Arto Lindsay, Lucas Santtana and, most recently, the sound-collage artist Alphayatch, Junix 11 has been a long-term partner of Giovani Cidreira and his Midas touch makes this album a goldmine for production nuggets. “Meninas Irmãs Pt.1”, gesturing towards a gentle Björk-like trip-hop beat, is a triumphant shimmer of shuffling drums, percussive violão plucks and occasional blooming string samples. Then, on the following title track, the producer builds a subtle accompaniment to the two singers, by sampling and warping their vocals with glittering reverb. Elsewhere, the plucked-string loop of “Meninas Irmãs Pt.2” tumbles headlong into a dynamic liquid groove. And on the following “Anos Incríveis”, the two vocalists, accomapnied by Josyara‘s guitar, engage in a lovely close harmony which is elevated with Junix’s sparse strings. The three talents – Cidreira, Josyara and Junix – find an uncanny middle-ground on Estreite between sparse and suffocating textures, easy melodic beauty and unsettling rhythmic and harmonic discordance, making for a fleeting yet affecting twenty-five minutes.

17. M. Takara & Carla Boregas – Linha D’Água (El Rocha Records)

Mauricio Takara – Hurtmold and São Paulo Underground drummer – is termed an “explorer of rhythmic regions” in the liner notes to his collaborative album with RAKTA and Fronte Violeta multidisciplinary sound artist, Carla Boregas. Indeed, in free-time and yet always dynamic, Takara finds pulse and rhythmic pockets in baggy, beatless spaces. At times on the opening title-track, you can’t tell where the water sounds end and Takara’s fidgety drums begin. The frenetic pace with which he shifts between toms, snares and cymbals is dextrous and precise – sometimes implying a regular pulse, sometimes pulling back and letting Boregas’ sound art to swell to the foreground. Indeed, the two counteract each other wonderfully throughout, with Boregas’ meticulous soundscapes – sometimes whirring synths (“Rosa De Areia”), sometimes field-recordings (“Linha D’Agua”), sometimes droning feedback (“Elipse”) – adroitly balancing Takara’s explorations. When arriving at “Mãe De Ouro”, a doom-jazz behemoth that sits halfway through the album, you are so immersed in the undulating wash of sound that air-raid-siren synths pulsate like soothing binaural beats and sharp harmonics sweep over you, shimmering and slippy. At once immediately arresting and quietly introspective, Takara’s drums drive where Boregas’ soundscapes dwell, making Linha D’Agua a superb commingling of two perfectly poised musicians in abundantly creative form.

Material originally sourced from the duo’s Under The Influence

16. Morris – Homem Mulher Cavalo Cobra (YB Music)

Homem Mulher Cavalo Cobra is an intricate statement – between its sinewy through-composed arrangements and its often-abstruse lyrical content, it can be a demanding 52 minutes. Indeed, the violão man, who sees his album as “profoundly entrenched in the MPB tradition”, draws from a rich wealth of Brazilian music that far surpasses the catchall acronym for Música Popular Brasileira. In fact, ideologically, the germ of Homem Mulher surpasses Brazil entirely, having grown from ideas set forth in Ai Weiwei’s RAIZ – the artist’s first exhibition in Brazil that intended to “reveal lost roots and threatened cultures”. Under the direction of meticulous arranger Romulo Froés, Morris’ first album in eleven years, sets itself structurally in response to Weiwei, being divided into four blocks: Death, Identity, People and Mythology. Opener, “Um Dia Lindo Pra Morrer” is brooding psychedelia in the vein of Lula Cortes. Morris’ singing leans on extended blue notes, adding tension until the piece bubbles over into frantic percussion. A structural curio that returns throughout this restless album is the pull and push of tempo and dynamics. And, similarly, the tone that songs begin with frequently shift drastically by their end. But as much as complex structures and polyphonic textures often obfuscate, Morris’ voice carries impressively, finding spaces and hitting notes that draw the ear among busy compositions.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #3

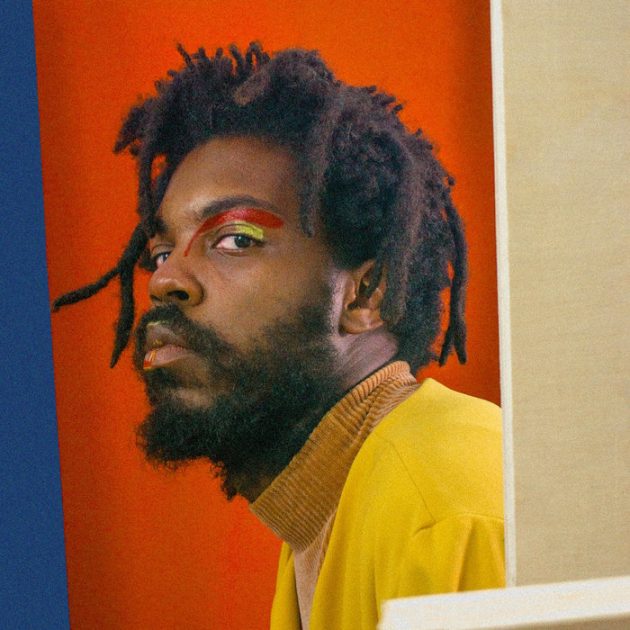

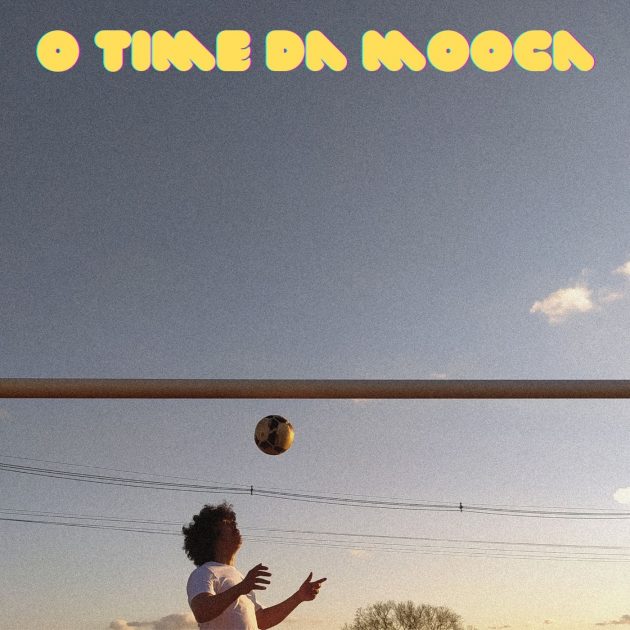

15. Ítallo – O Time Da Mooca (Self-Released)

Ítallo’s sunny sophomore release is the most archetypally Brazilian record of the year. The album name which means “Team Mooca” is stamped, in retromanic typeface, atop a sun-bleached snapshot of its protagonist juggling a football. The album’s cover couldn’t look be more evocative of a Brazil romanticised of world-over. And Ítallo’s music is a buoyant collection of updated Brazilian cultural signifiers – plenty of shuffling caixa, fluttering pifanos, organ and funk bass, which underpin coming-of-age tales set in Ítallo’s hometown, Arapiraca, Alagoas. The title track is an instantly enchanting MPB-funk crossover in the mould of ‘70s Di Melo. Regaling with stories of street-football, it’s a sublime two and a half minutes that, delivered with the slack grooviness of Orlandivo and the squeaky vocal tone of Gilberto Gil, recalls golden-era MPB. “Breno” is a brief bossa nova – stylish and casually understated. And “Duas Ximbras”, which begins with a descending vocal pattern that evokes Tim Maia’s “O Caminho Do Bem”, swings via neat harmonies towards a drifting violão meditation. Everything on Ítallo’s album sets a sepia mood – these short tracks are often content with piling up like yellowing snapshots that evoke warm nostalgia without revealing lifelike detail. But when more well-crafted songs breeze by – “Orlando Golada” and “Camisa Do Flamengo” in particular – you are transported to MPB‘s golden days in vivid colour.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #4

14. Iara Rennó – AfrodisíacA (Iara Rennó, Macunaópera Produções Artísticas LTDA)

On her website, Iara Rennó ruminates on her latest project, AfrodisíacA: “Is it a series? Is it music? Is it poetry? Is it an operetta? Saga? Is it food? Is it listening? Something to see? It is a bit of everything.” Rennó continues, evocative of Herbert Marcuse’s Eros & Civilisation: “Those who are our enemies, who oppress us, kill us, do everything to end our ability to feel pleasure. Our joy is their grief. Let us show that our libido can do more.” Call it what you want, experiencing AfrodisíacA struggle for musical freedom is wholly captivating. Ridding itself of a regular album structure, Rennó’s album is made up of chapters – each of which comprise of at least one spoken-word collaboration (reminiscent of Walter Franco’s or Caetano Veloso’s in the seventies) and one atmospheric, ominous jam-song. Meanwhile, each chapter becomes a palimpsest of diverse voices as Rennó enlists a mouth-watering roster of Brazil’s most innovative artists to collaborate – Anelis Assumpção, Tulipa Ruiz, Ava Rocha and Negro Leo, to name a few. The outcome is a messy web of sounds that evade classification. The Negro Leo composition “Tara” melts into a loose wash of Gal Costa cackling and a swung hi-hat. Meanwhile, on the thudding “A Não Ser Que Me Ame”, Rennó’s wail resembles the snarled vocals of Teto Preto’s Laura Diaz. Her adaptation of the song co-written by Rodrigo Campos and Rômulo Froes, builds to an epic climax like a Bond theme for the uninhibited.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #2

13. Mateus Aleluia – Olorum (Selo Sesc)

That the vocals are spectacular on Mateus Aleluia‘s Olorum is unsurprising. The leading voice belongs to a past member of Afro-Brazilian choral trio Os Tincoãs and has aged like whiskey in an oak barrel. Full and gruff, yet still fluttering and feather-light when in falsetto, Aleluia sings like a sunbaked blues singer, bursting with soul. He is commanding on the rousing title-track, invoking the titular Yoruba orixa, pleading for the end of earthly suffering above militant gang-vocals. The following “Kawô Kabiyesilê”, plaintive and sparse, gives the 76-year-old space to stretch further: each vocal chord crack, each gliding glissando between full-bellied baritone and falsetto, sending shivers. Underneath, earthy violins and tip-tapping percussion make for delicate accompaniment. Olorum begins tender, raw and meditative – an impassioned exploration of Afro-Baroque traditions by a man who spent the best part of twenty years in Angola studying native culture and spirituality. But midway through the João Donato collaboration “Amarelou”, Aleluia’s album shifts into a lighter mood. Effortlessly, the plucked violãos and percussive flittering peel away and a signature Donato lounge-funk groove glides into gear. Fit with female backing vocals and syncopated keys, it’s a refreshing moment on an album that’s always dazzlingly pretty but occasionally ponderous.

12. Letrux – Letrux Aos Prantos (Self-Released)

As Letícia Novaes (AKA Letrux) extolls bodily fluids on the rousing “Déjà-Vu Frenesi”, a glimmering soundscape starts swelling around her, dressing her smut in something sumptuous. Sparkling percussion and drum loops spit and hiss like Letrux does, but funeral organs and crunching guitars drape an affected dignity atop her championing of “tears, sweat and cum”. Equal parts pulp fiction and po-faced performance, Letrux Aos Prantos is a commingling of faux ostentation and lewd humour that beds down between bare-faced Phoebe Bridgers and gyrating Jarvis Cocker. To read the lyrics online to “Fora Da Foda” – a campy ’80s floor-filler with infectious cowbell and speak-sing vocals – a website asked I confirm my age. But her profanity is always comic, not provocative. Above a saccharine synth outro, a hot and breathy Letrux observes: “It’s so hard to find the right people to fuck / Threesomes are hard, an orgy is harder”. And, for all its pomp and potty humour, Letrux Aos Prantos can be elegant and startlingly poignant. Case in point: “Dorme Com Essa”, a lush synth-pad break-up song that turns on a “choking” double entendre. After a chorus that begs an old flame to “Sleep with this/ Sleep with her/ [But also] sleep with me”, the whirring accompaniment whisks the piece to a weepy height, with a wistful Letrux crying: “I was delirious/ I thought I saw you on Copacabana/ But it wasn’t you.” In fact, by album curtain-call, suitably titled “Cry Something Awkward”, Letrux has made you laugh, cry and cringe as if you were deep in the throes of an imprudent yet intoxicating fling.

11. Thiago Nassif – Mente (Gearbox Records)

“Você tem me feito soar estranho” (‘You’ve been making me sound strange’), Thiago Nassif accuses on Mente opener “Soar Estranho”. Chewing up and spitting out lurching lyrical snippets over stumbling buzz-saw synths, Nassif certainly doesn’t need help sounding strange. The no-waver’s latest album, produced by ex-Lounge Lizard, Arto Lindsay, was always going to sound awkward and eccentric. Less expected though? Heralded by a thudding drum roll, though, “Soar Estranho”’s stumbling build-up somersaults into sure-footed funk. The stagger very quickly becomes swagger: “You left your number on my fridge/ And yet you’re so out of reach,” sing chorus-laden female vocals over a stomping rhythm section. With breakneck speed, Mente’s eccentric opener lurches and jolts into gear. And its Nassif’s shifts from po-faced esotericism to visceral funk and accessible humour that makes Mente so captivating. The album’s title plays on a Portuguese homophone – to lie (‘mentir’); mind (‘mente’). Fittingly, Mente is ever-elusive and polymorphous: just when you lull into the distortion laden stutter-strut of “Pele De Leopard”, the album moves into the spacious “Voz Única Foto Sem Calcinha” with cuícas, gentle guitar and female vocals courtesy of Ana Frango Elétrico. Then comes album highlight: “Plástico”, with Nassif muttering, like a high-Modernist Baxter Dury, about plastic bags over bubbling guitars.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #1

10. Seu Jorge & Rogê – Direct-To-Disc Sessions (Night Dreamer)

To listen to Seu Jorge’s and Rogê’s brief collaborative album is to pore over a yellowing carte de visite of two old friends sharing a quiet evening. The two MPB performers, who have been close since the late ’90s when they were both young players on the Rio circuit, have worked together before – Rogê has written for Jorge; Jorge has featured on Rogê’s 2016 single “Presença Forte”. But it’s on their intimate Night Dreamer session that their voices really glow, together, for the first time. Over a gentle, unhurried half an hour, the listener is privy to what feels like a private moment between two friends engaged in a nostalgic rummaging through shared stories and memories. Recorded in single takes over four days, the seven tracks are collected from an archive of unrealised songs, sketches and ideas, both individually and co-written, and include the tender “Caminhão”, a quiet duet penned 25 years ago. Stripped back to violão and vocals (with unobtrusive percussion accompaniment), Jorge’s and Rogê’s voices glimmer in the sparse texture, with Jorge’s baritone wonderfully offset by his counterpart’s syrupy tenor. It’s one of a handful of performances that are right up there with the best of both artist’s catalogues – like the group sing-a-long “Saravá” and the buoyant “Onde Carioca”. But its the album’s quiet, meditative moments that truly charm – the atmospheric Afrosamba “A Força”, and the cute duet “Pra Você Amigo”, an ode to friendship during which the nouns “amigo” and “irmão” are used interchangeably by the two besotted musical brothers.

9. Luedji Luna – O Bom Mesmo É Estar Debaixo D’Água (Self-Released)

Joyce Prado’s lush video accompaniment to Luedji Luna’s visual-album begins with the pull and sway of the Salvador tide. Both visually and sonically, water is a prevalent force in Luna’s music. Babbling instrumentation becomes, quickly, thematic – the candomblé percussion on opener “Uanga” can attest to that. Equally, the uninterrupted flow from one song to the next makes the album a wholly immersive underwater experience – one song heaving languidly towards the next, like an unbroken roll of the ocean. Above the percussion, on “Uanga”, poet and composer Lande Onwale sings, in a hybrid of Portuguese and Angolan Kimbundu: “O amor é Coisa que moí muximba/ E depois o mesmo que faz curar” (“Love is the thing that breaks the heart/ And, after, the same thing that heals it”). Bom Mesmo…’s thematic concerns are introduced by one of very few male voices heard during the album’s 50 minutes. Indeed, in Luna’s words, Bom Mesmo… is “a reflection on the affectivity of black women”. And, for her, such a topic warrants profound interrogation of love – “the primary source […] contained in every atom”. Throughout, Luna ruminates on black female intersectionality, dialoguing with candomblé spirituality, historic female voices and contemporary Brazilian artists. Underpinned by a sumptuous blend of Afro-Brazilian rhythms, North American soul tradition, Caribbean reggae varieties and contemporary Brazilian R&B, the result is rich, layered and shimmering with beauty.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #4

8. Vovô Bebê – Briga Da Família (RISCO)

Briga Da Família is an exemplar practice in deconstruction. Throughout Pedro Dias Carneiro‘s latest album, compositions that begin thick and crunchy unravel to their most sinewy form: writhing guitar and bass riffs, frantic drums and, as often as not, Ana Frango Elétrico‘s guest yelping. To arrange such unravelling without each piece losing momentum is no mean feat, and highlights Carneiro’s masterful control of rhythm. “Sabidão Sabe Não”, with its implied double-time trickles through frequent pauses with fluency, helped along by syncopated guitar squeals and horn stabs. Then, “Foda-se” overlays triplet guitar and woodwind parts atop a reggae drum pattern to create a buoyant contrapuntal platform for his surreal vocal: “Walk barefoot/ Step on the callus/ Go to the pack/ Sing to the wind”. The absurd lyrics spiral on the Itamar Assumpção-influenced “Jeggae”. “Jeggae carried the coconut on the bullet”, Elétrico proffers, before Carneiro interjects: “Says the cat!” As the lyrics proceed with incessant repetition, comparisons to Assumpção go beyond the inclination for reggae rhythms and polyphonic melodies; Carneiro’s repetition evokes Assumpção’s experimentation with concrete poetry. When discussing album highlight “Orfão”, Carneiro identifies the piece as being about “forced self-sufficiency and fear. In the end, we fall into chaotic improvisation, as is common in life.” Sure enough, the crunching funk guitar, whirligig woodwind and circus percussion tumble into chaos towards the track’s close. But Carneiro’s band stays sufficiently groovy throughout the unravelling chaos.

7. Negro Leo – Desejo De Lacrar (QTV)

Negro Leo, at the sharpened edge of Brazil’s MPB vanguard, released his freest full-length this year. Desejo de Lacrar is loud and unshackled – a collection of spontaneous-sounding bursts of expression that shift styles, tempos and volume at breakneck speed. Sonically, the result can be as bewildering as it is breath-taking. The often incongruous amalgam of sounds could have been stumbled upon if Thundercat were to enlist Deerhoof to make a Flying Lotus-produced Hermeto Pascoal tribute album. And, for some reason, on Desejo, that makes perfect sense. Fluttering between free jazz, art-rock and experimental electronics, Desejo struggles for total musical freedom, sonically aligning with its title’s sentiment. Desejo de Lacrar – which translates to ‘Desire to Seal’ – borrows LGBTQ+ terminology to express feelings of defiance. Leo explains: “To seal is to act insolent and revolted. To win, if not in fact, then virtually.” On Desejo, Leo, explores the eponymous verb in relation to his native nation’s systemic transphobia, homophobia and racism. His music refuses pigeonholing, revolting against total normativity. From the opening title track, Leo’s lyrics – a fusion of abstract esotericism and jazz scat – are screeched and whooped, breaking through the boundaries of a male singer’s conventional register, reaching an inhuman falsetto. “Somos todos” (“We are everything”) ends “Desejo de Lacrar”. In Whitmanesque sentiment, Leo suggests an alternative, repairing collectivism which concords with his free fusion music.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #1

6. Joana Queiroz – Tempo Sem Tempo (YB Music)

On José Miguel Wisnik’s “Tempo Sem Tempo”, the composer and essayist’s lyrics tug at the construct of time: “Time goes around and around . . . It is and is not at the same time”. After seeing Wisnik perform live, the song and its concept began looping in Joana Queiroz‘s mind, slowly spiralling toward becoming the theoretical centre-point for the clarinettist and saxophonist’s latest album. For Queiroz, both in practice and theory, looping (“time go[ing] around and around”) was going to be key on Tempo Sem Tempo. She set about arranging compositions so that she could play them herself, utilising loop pedals to build elaborate textures. The point? To challenge the idea of live-ness. Indeed, while each composition sounds organic and of-the-moment, it’s made up of loops that are inherently no longer live the minute they’re made. Each instrument, to paraphrase Wisnik, both “is and is not at the same time”. Working under this logic, on Tempo Sem Tempo Queiroz assembles an enthralling collection of delicate, gossamer layers. On opener, “O Barco”, it is a full two minutes before you hear a proper note of music – what precedes is ASMR-inducing breath- and valve-work which ripples down the spine. It, then, builds slowly, with breathy drones and scalic patterns, spiralling, unbound by any exact metre. Indeed, Queiroz’s record isn’t interested in linearity; rather, it is a record that is spacious, moving delicately from one idea to the next.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #1

5. Sztu – Lances (Selo Traste)

Under the unassuming nom de plume Sztu, visual artist André Sztutman dropped his debut solo musical work Lances at the end of August to little pomp. Its under-the-radar release was certainly a suitable entrance. Not because Lances doesn’t deserve rapturous praise – it certainly does. But, because Sztutman’s debut truly savours its spaces and silences. Delicate, meticulously arranged and full of vivid melodies, it is a perfectly composed picture that, from Sztutman’s minimalist cover-art to the 27-minute running time, understands how sometimes less is so much more. Highlight “Nenhum Um”, beginning with Sztu’s quiet divulgation “Nada nas mãos” (“Nothing in my hands”), trickles along pensively in 7/4 before intricate percussion, plucked violão and a diminished electric guitar whisk the piece into a faux-epic stratosphere. “Bicho Esqueredo” is richly textured, with jubilant horns and pifanos fluttering. Meanwhile, “Rasgar O Pano” is an luscious samba awash with delicate percussion, cuica and chorus-laden guitar. There’s a wonderful descending motif that sounds almost lifted from Haroldo Lobo’s “Tristeza”, and it’s hard not to draw comparisons between “Rasgar…” and the role “Samba De Orly” plays on Chico Buarque’s ground-breaking Construção. Sztutman identifies Lances as an entrance into the “sacred ring of MPB“. And, as one of contemporary MPB’s most quietly complex statements, it’s an entry that deserves to become as canonical as his sacred influences.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #2

Find our feature-length interview here

4. Tantão E Os Fita – Piorou (QTV)

The shimmering vocals on “Introdução ao Piorou” is key to understanding Tantão e Os Fita’s third album. The choir – which is erratically interrupted by thudding feedback – is mesmeric. As if recorded in a cathedral, the voices reverberate, creating harmonics that shoot chills as much as its devastating feedback interruptions do. Before getting in to the ring with Tantão E Os Fita’s, then, it’s important to understand that this record is not just a screaming-match; it’s not a musical survival-of-the-fittest. Piorou is a painstakingly arranged, sinewy tour de force, which floats like a butterfly as well as stinging like a bee. Indeed, the trio do do conventional prettiness. But, there’s also beauty in Piorou’s most seething aggression. On the title-track, producers Abel Duarte and Cainã Bomilcar hook up a trap beat to jump leads and shock-torture it into submission. Carlos Antônio de Mattos (aka Tantão) bellows over the top: “Piorou/ Vai piourou” (“It got worse/ It will get worse”), as if the listener hadn’t got the distressing message via the instrumental. Later, two-thirds of the way through the album, we hear one of the most prickly feedback-infused pieces, “Bonito”. On its chorus, Tantão repeatedly barks the adjectives “bonito” (“pretty”) and “feio” (“ugly”). With each spat-out adjective, Tantão pitches the binaries against each other, inviting the listener to compare terms. For most listeners, this onslaught of trembling feedback and growled vocals would be undeniably ugly. But, it’s titled otherwise. Even at its nastiest, Piorou can be exhilaratingly beautiful. It’s instantly engaging, overwhelming, blood-curdlingly brazen and totally unique.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #4

3. Kiko Dinucci – Rastilho [Deluxe Edition] (Mais Um Discos)

On January’s Rastilho, Metá Metá’s Kiko Dinucci wielded his guitar like a weapon to captivating results. For a record compromising of voice and guitar only, it is remarkably dense – tangible, and rough to the touch. His technical mastery enables Dinucci to deftly traverse the limits of his instrument, with the acoustic guitar often doubling up as a whole bloco of percussion as well as colourfully accompanying gentler moments with rich extended chords. Dinucci’s album has been consistently likened to Baden Powell and Vinicius De Moraes’ Os Afro-sambas – the female chorus on “Vida Mansa” or the title-track’s outro substantiate the comparison. But while the 1960s masterpiece finds a brooding atmosphere in its quietness and dark corners, beyond its brooding intro “Exu Odara”, Rastilho is breathtakingly immediate and uncompromisingly clamorous. With Dinucci spending the 90s, equal parts, in São Paulo’s hardcore scene and partaking in candomblé activities, Rastilho incorporates both influences in equal measure. Indeed it’s an album that can flip from seething to sweet with exhilarating speed. On Mais Um’s reissue, Dinucci’s visceral violão thrashing finds its sweet counterpoint in the Ava Rocha feature “Habitual” and gorgeous Juçara Marçal collaboration “Gurufim”. But, the São Paulo guitarist is most emphatic when his guttural vocals and overwhelming guitar-work is front-and-centre, at spitting-distance from the listener.

Originally found, unabridged, at Mais Um’s Rastilho Première

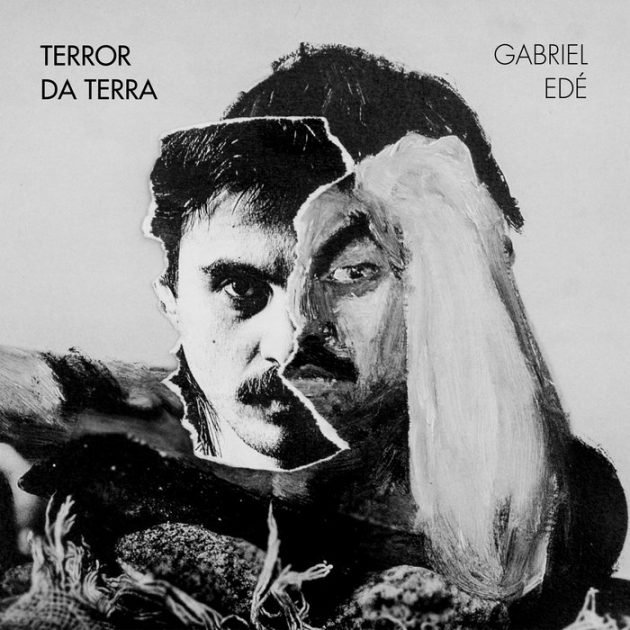

2. Gabriel Edé – Terror Da Terra (TUDOS)

Terror da Terra is theatre. To enter its world is to thrust apart stage curtains, embrace the orchestra’s swell, and to sink into a plush velvet mood. Forestalling its dramatic shadows and dense orchestration, Terror’s artwork, with viscous brushstrokes, is thick and sinister. A sombre rendering of its lead dramatist, it shows Gabriel Edé propped up at the elbow. His head, resting on a clenched fist, pulls his eyebrow into a raised incredulity. The music on the Chilean-Brazilian’s debut album is accordingly dark and inquisitive – its lyrics prodding at egoism, pulling apart autonomy and prophesising apocalypse. The eponymous opener prowls with funeral-march brass and strummed violão swelling towards climactic gang vocals, saxophone puffs and drums which rumble like a cavalry charging. After, the Negro Leo collaboration, “Baby Blues” is a drunk, stumbling number bashed out, stride-piano style. With chopped-up saxophone samples that judder and squeak, it seems a playful piece. But, as Edé’s lyrics tell a groaning tale of post-natal depression (“I was born, you cried, you lost all the sparkle, I stole your sun”), Leo’s crying-baby impressions shift from silly to tragically powerful. A squawking pastiche of its titular music genre, “Baby Blues” shares the bewitching tone of a tragicomic Charles Mingus romp. On Terror da Terra, Edé proves he can find, in equal volume, striking beauty, and black comedy within the darkness.

Originally found, unabridged, at Brazilian Wax #3

1. Ilessi – Dama De Espadas (Rocinante)

Trace Ilessi‘s far-reaching roots and you’ll find that the Campo Grande-born and Jacarepaguá-raised singer-songwriter has contributed to an abundance of diverse Brazilian and worldwide musical conversations since 1998. In 2014 she launched the show Nos túneis de mangueiras showcasing music exclusively from the Amazon-mouth state Pará; in the same year she started a year-long improvisation course in Sweden; later, in 2018 she worked on a tribute to Baden Powell, while also producing events for women in music all over Brazil. But when listening to Dama de Espadas – Ilessi’s sprawling kaleidoscopic full-length – it’s evident, from her Gal Costa scat-wail to the Gilberto Gil tribute song, that this Carioca singer is musically indebted to late-60s Bahia.

On Dama, Ilessi draws on the tropicalistas‘ visceral instrumentation, melodic acrobatics, and cultural cannibalism, intertwining her blues and jazz-improvisation schooling and Afro-Brazilian heritage to weave a vibrant and tactile tapestry. Dama de Espadas leaps from aching blues (“Dama de Espadas”) to celestial Club-Da-Esquina MPB (“Lírico”), Build Up-era Rita Lee (“Mar de Te Amar”) and Joyce Moreno folk-psych (“Desperto de Você”) with the playful and impassioned ease of Tropicália‘s trailblazers. And when the jolting “Vivo Ou Morto” stumbles in, like a cut from Gal Costa’s coveted 1969 records, Ilessi’s alternately commanding and cackling vocals are uncannily resemblant of the Bahian’s.

Besides tropicália, though, Dama de Espadas is both musically and theoretically interested in exploring Afro-Brazilian hybridity and Black identity – most obviously on the spoken-word “Eu Não Sou Seu Negro”, its title lifted from the 2016 documentary based on James Baldwin’s unfinished novel, Remember This House. The two cultural traditions – the Afro-Brazilian and the tropicalista – are married throughout the sprawling 49 minute epic, certainly in the blend of blues and jazz sensibilities with psychedelia. And, also, on the majestic album closer : a cover of Suka’s “Ilê de luz”, an afoxé track recorded famously by Caetano Veloso and Ilê Aiyê. On her enthralling album, Ilessi blends the melodic, harmonic and rhythmic freedom of jazz with the aesthetic genre-bending freedom of Tropicália and creates a lush musical landscape to get lost in.

Listen to Brazilian Wax’s Top 21 below:

Follow Brazilian Wax:

Website / Facebook / Instagram / Soundcloud / Mixcloud

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.