Another Possible Conclusion: An Interview with Mexican Writer Yuri Herrera

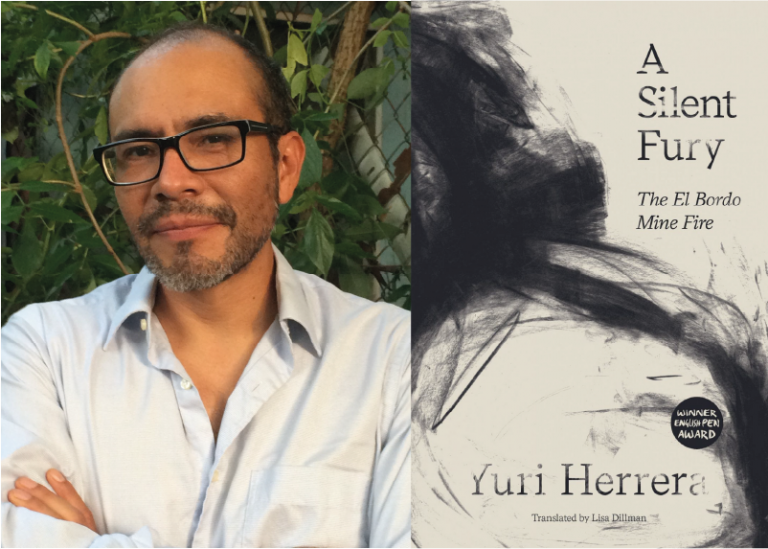

16 July, 2020Yuri Herrera is an acclaimed Mexican author, best-known for the novel Signs Preceding the End of the World which was chosen as one of the Guardian’s 100 Best Books of the 21st Century and won the 2016 Best Translated Book Award. He is the author of The Transmigration of Bodies and Kingdom Cons and his most recent book is his first non-fiction: A Silent Fury: The El Bordo Mine Fire. Herrera spoke about his recent work (and his earlier novel set during a pandemic-induced lockdown) from his home in New Orleans.

A Silent Fury is the devastating account of a huge fire at El Bordo mine in Pachuca, Mexico, in 1920. It tells the story of the horrifying events of the fire and the survivors’ six days shut inside the mine, the victims’ stories and the ensuing cover-up. Pachuca is your hometown. How well-known is the El Bordo mine disaster in Mexico?

It is a story that people whose families have been in Pachuca for more than one generation knew about; you still can talk to people whose grandfathers were miners at the time. And there were a couple of pieces written years later, but not a comprehensive version of them.

Your PhD research informed A Silent Fury, though you say in A Silent Fury that the two projects have different aims: the former is about “analysis of the materials…recording the history” and the latter is about “making the story and its protagonists visible”.

Yes, this is a book that was meant, first of all, for the people of Pachuca, for the ones who have kept this story alive, and for the ones that live in the city but do not know about a chapter that, for me, is crucial to understand our history. Both works are based on an analysis of the existing sources, but A Silent Fury is my attempt to make narrative sense of them, while leaving room for the readers to appreciate also the importance of the silences.

Speaking of silences, could you comment on the title A Silent Fury? This phrase comes from your commentary on one of the few photos taken in the aftermath of the fire: a photo of the survivors.

I love it. It is precise and fair. It comes, indeed, from the description I am making of one of the survivors. This is one of the few moments where I allow myself to do some speculation about what I’m seeing to underline our impossibility to know that side of the story. This picture that we are seeing of the survivors cleaned up and dressed all in white is a photo op, but that there is something in the face of one [of the men] that makes me suspect a sort of silent fury.

This is your first non-fiction book. Is non-fiction harder to write than fiction?

It is a different kind of difficulty. With a book like this you are constrained by the existing sources. That limits your vocabulary and the possibilities of the story you are trying to tell; at the same time, it makes you look harder, dig deeper on the elements of the narration.

A Silent Fury is a short book: 120 pages. How did you decide on the structure?

I wanted to tell the story at a fluid pace, to give the reader an organic version of the facts as much as possible because very often the atrocities done to the dispossessed are told as episodes that cannot be explained or reconstructed (for example, what the previous Mexican government said about the kidnapping and murder of 43 students in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero), but while giving importance to the silences there as part of the story, not as an impossibility. So in these chapters I made a point of taking a step back and paying attention to what we are seeing, to the silences produced by the powerful people in this story, and what we could hear from the people that have been silenced, in spite of that.

How did you manage the balance between your work uncovering the facts of this 1920 story and your present-day commentary on it?

I try to not intervene explicitly as much as possible (that is, after the most obvious intervention, which is choosing to tell this story and challenging the official version of it). However, I also do not try to conceal the fact that this story is not about a world that no longer exists, but that it is part of the genealogy of impunity as a system that still operates in Mexico: a continuation of a colonial order. So when I am researching about this old story, I am also researching about our current time.

Your novel The Transmigration of Bodies takes place during a plague that has sent a Mexican city into an eerie lockdown. Has the Coronavirus pandemic caused you to look at this novel in a different light?

I started thinking about this book long before I started writing it, and I was taking notes on it when the AH1N1 [swine flu] scare happened in Mexico City, where I was living at the time, so it gave me some first hand material to write it, but it was not the definitive factor. What I think is that fiction is less about doing a portrait of what already has happened than taking some elements of our time to another possible conclusion. So in that sense, I think what The Transmigration of Bodies was doing was reading certain things in the world that were allowing an epidemic – and its social reaction – to happen. And all those are still here, with or without vaccines. This is not an act of god but a tragedy of our own m making: a consequence of the criminal way in which we interact with nature, the destruction of our health systems, how we live on top of each other, how we travel.

Signs Preceding the End of the World was published in 2009 in Spanish and 2015 in English. Most of the book takes place in the borderlands between the USA and Mexico and the story of migrants travelling to the US is still pertinent today. What’s your relationship with this novel in 2020?

I am a migrant: a privileged one but still a migrant, and I am close to the migrant community in New Orleans. This is a book that for me says something directly relevant to my life, to my language, and to the way in which I try to work with the elements of reality to create art, trying to be respectful in regards to what you see but also not constraining the people populating [the] stories to mere narrative functions or to binarisms. Migration is one of the great events of our times and it deserves to be understood in all its complexity. I tried to do that and maybe that is why it is still being read.

The main character of Signs Preceding is Makina: she undertakes a sort of mythical journey to the USA to find her brother. How did this character come to you?

As soon as I was clear that this would be the story of a voyage, I immediately had clarity that the protagonist was going to be a strong, clever woman. It is maybe because I have seen, in my moving around different places, that migrant women are the toughest human beings around. Also because I had the privilege to grow up surrounded by strong women: my grandmother, a midwife, nurse, social worker, my mom, a doctor and political activist.

What’s your involvement in the process of translation of your books into English and other languages?

I get involved as much as the translators want. I do not want to micromanage the translations, even though I enjoy being part of the process. I assume that translators are professionals that know their language and their readership much better than I do. In the case of the English translations, Lisa Dillman has been in close touch with me while translating all my books, in some cases exchanging daily emails for months talking about the nuance of certain words or the possible solutions for a word that I made up or put in a different context. I love her work. [Dillman writes about translating Herrera’s books here.]

The books we mentioned cover huge political themes: migration, violence, abuse of corporate power… How do you feel about being considered a political writer?

Labels are useful for marketing and in certain academic papers and to organize your bookshelves. They constrain the multiple meanings of a work to a handful that make it more manageable; they are unavoidable, so I don’t mind them. “Political writing” is an extremely broad one, since, to begin with, any literary text can be read from a political standpoint. How you understand language, hierarchies, gender, or wealth, expresses a certain political position; but also because, yes, I am very aware of the debates in the public sphere and those get in the writing one way or another.

Signs Preceding the End of the World, The Transmigration of Bodies, Kingdom Cons and A Silent Fury (all translated by Lisa Dillman) are published by And Other Stories.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.