Guajira – the lonely voice of the desert

28 April, 2011Our next destination was supposed to be the Cauca mountains, home to the Nasa people in the South West of the country. But with the rainy season at its peak, the two only roads to Calderas, the main town we were visiting, were closed. Colombia is flooded. The country is in the midst of the worst rain, floods and landslides ever recorded in history.

The news talk about 80% of the country being in a state of emergency. We decided to escape the rain while we could, and headed north to La Guajira, Colombia’s northernmost province.

La Guajira peninsula is a semi-arid desert, surrounded by the Caribbean sea. It is home to the strong-willed Wayuu people, which have inhabited this harsh land as semi-nomads since long before the Spanish conquest. They say the Spaniards started coming to the peninsula looking for treasures buried by pirates. They brought goats, horses, and cows – now fundamental to the Wayuu way of life – as gifts for the locals in exchange for the treasure’s location. They also came looking for pearls, taking advantage of the Wayuu’s diving abilities. The natives managed to stay fiercely independent by developing trading skills – which they use up to these days in contraband of all sorts of goods – and becoming the first indigenous group in Colombia to be armed with fire weapons.

The Wayuu are a matri-lineal society, grouped in 32 clans which are identified with different animals. It is still common for men to pay a dowry to marry women, in the form of large amounts of money or its equivalent in goats, horses, cattle and jewelry. The Wayuu women are famous for their beauty, artistry and strong will. They spend their days looking after the goats, walking for kilometers to find fresh water and gather wood, cooking and weaving exquisite mochilas (handbags) and chinchorros (hammocks). Men usually leave early at dawn to fish and return to the rancherias (groups of huts made of dried cactus) to help with the goats.

First, we arrived in Riohacha, capital of the Guajira. We took a walk under the full moon on the city’s long walking pier, that goes for nearly a kilometer into the sea. It is an impressive sight at high-tide. You can feel this is the northernmost point of South America. We sang and played instruments with Teto Ocampo, who also joined us for this portion of the trip. The wind never ceased to blow strongly from the sea. It was always the most prominent sound, swallowing all others.

The next day we headed to Uribia, 2 1/2 hours by car deeper into the desert. We met with Joaquin Prince, the director of Saüyee Pia, the only Wayuu school for traditional art, music and sports in the region. He explained a lot about Wayuu culture and their efforts in continuing their traditions. He’s one of the people responsible for inscribing the Wayuu way of life in the world’s “intangible cultural heritage” list of the United Nation´s Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

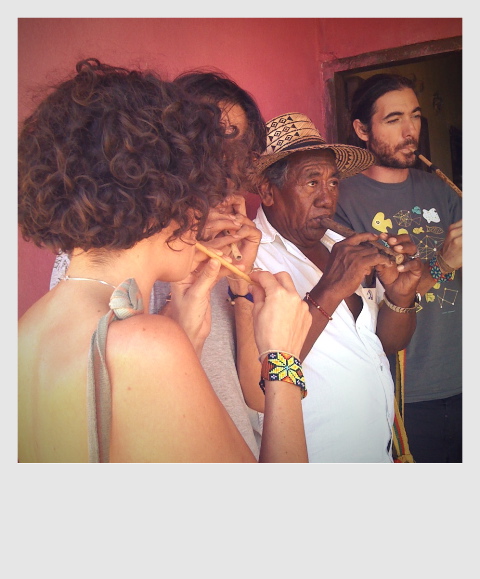

Later, we met Jorge Henriquez, in Media Luna, a nearby rancheria. Jorge is an elder palabrero, a key figure in the Wayuu community that combines the roles of lawyer, spokesperson, counsellor and teacher. He plays all of their traditional instruments, mainly flutes (maasi, sawawaa, ontoroyoi, jiraway) made from various canes, the trompa (mouth harp) and kasha (drum). All the Wayuu traditional instruments are played a capella, unaccompanied by anything else. The music is made while in solitude in the desert; and its melodies and rhythms sound closer to the sound of the wind and the birds in the desert than to human-made sounds.

We spent the next 3 days in Cabo de la Vela, a pointy cape on the higher part of the peninsula. The landscape seemed even more from a dream: the sand dunes, cactus and rocky cliffs surrounded everywhere by the deep blue ocean waters. We played music with the ever-present wind, and sometimes the wind played our instruments without us.

On our way back south, we went through Uribia to hear Cecilia Bonivento a traditional Jayechi singer, who showed us this intricate singing style, where the singer adds her/his own melody to lengthy lyrics from an old oral-tradition.

We are very happy that we got to collaborate with both Cecilia and Jorge Henriquez; it was a rare opportunity.

Follow Sounds and Colours: Facebook / Twitter / Instagram / Mixcloud / Soundcloud / Bandcamp

Subscribe to the Sounds and Colours Newsletter for regular updates, news and competitions bringing the best of Latin American culture direct to your Inbox.